Thursday, 5:00pm

2 December 2010

Horse play

Eadweard Muybridge’s miscellaneous acts of captured motion

In ‘Adventures in Motion Graphics’ in Eye 77, we explored how time-based picture taking (in forms such as slideshows, film, ‘motos’ and long portraits) were transforming traditional photography, writes John Ridpath. But one practitioner was already blurring the boundary between still and moving images more than a hundred years ago.

Eadweard Muybridge, currently featured in a Tate Britain retrospective, left behind a legacy of incredible images. Marta Braun’s new book Eadweard Muybridge, the latest in Reaktion Books’ Critical Lives series, explores the dramatic life that lay behind the career of this eccentric photographer.

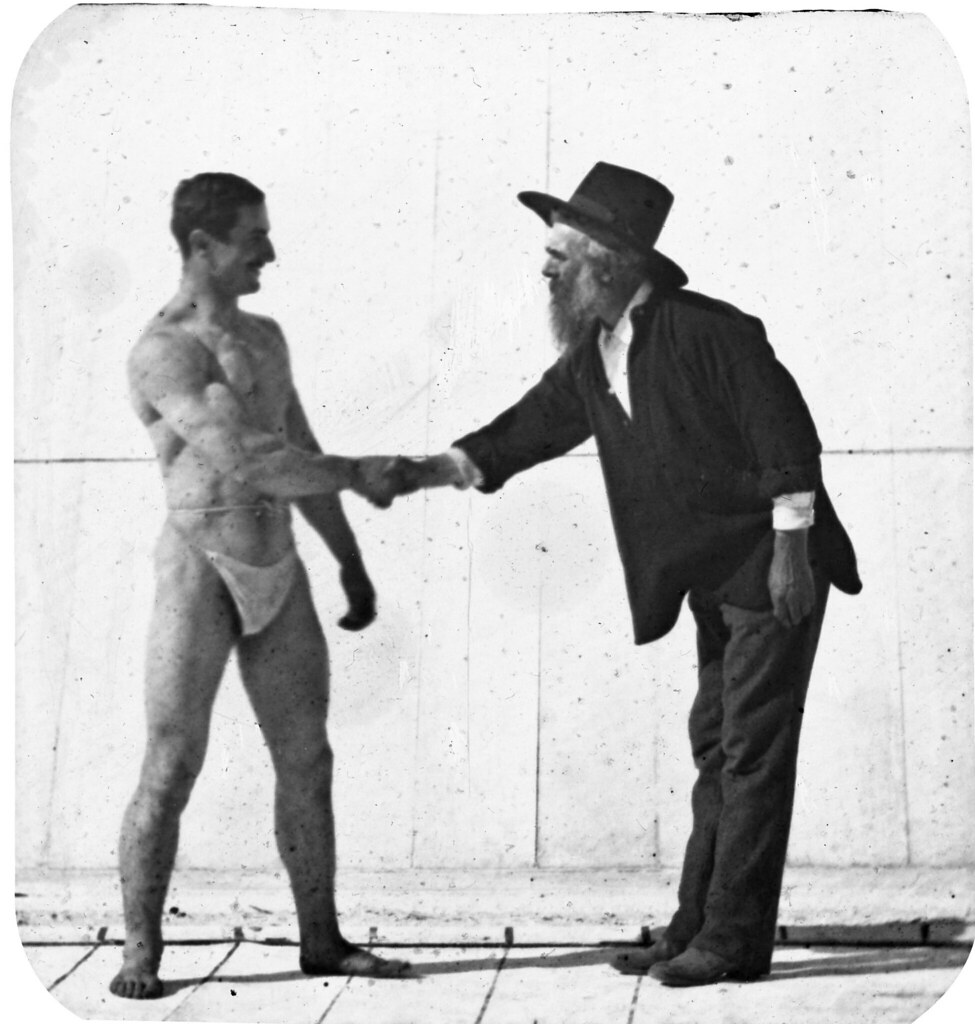

Top: Muybridge posing with San Francisco Olympic Club strongman L. Brandt (1879).

Born Edward James Muggeridge, the photographer changed his surname first to Muygridge, before settling on Muybridge and the rather more exotic / antiquated first name Eadward. In the 1870s, he sometimes worked under the artist name ‘Helios’. Early work from that period includes his photographs at Woodward’s Gardens in San Francisco, a complex of attractions including a zoo, an amusement park, four museums and an art gallery. Muybridge photographed the leisure spot’s prized stuffed animals alongside his future wife Flora to surreal effect. The images might seem distanced from his more famous motion sequences, but with them the photographer was already toying with the tension between stillness and movement.

Above: ‘Animals at Woodward’s Gardens’ (1870).

Below: ‘Scene at Woodward’s Gardens’ (1870).

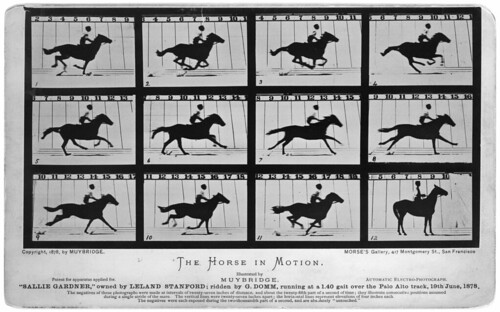

Muybridge made his first contribution to the development of motion pictures with his infamous photography of galloping horses. These experiments culminated with Animal Locomotion (1887), a a book of 781 photographs containing almost 20,000 individual images that has never been out of print since its publication.

As Braun points out, it is important to remember that this work is not one of scientific objectivity – he selected, edited and manipulated his prints: ‘what was critical for him was the appearance of congruency of the images in the print, the appearance of a logical progression and the picture’s aesthetic appearance. Throughout Muybridge’s work, the facts presented to his cameras and the picture of those facts he offered to the viewer often differered. He used his cameras as much to construct and deconstruct visible reality as to replicate it.’

Above: ‘The Horse in Motion’ (1878).

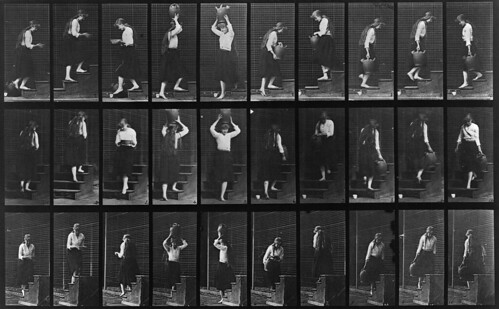

Below: Blanche Epler ‘Ascending and descending stairs’, from Animal Locomotion (1887).

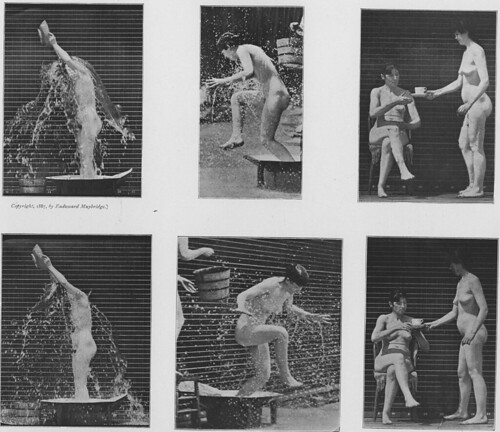

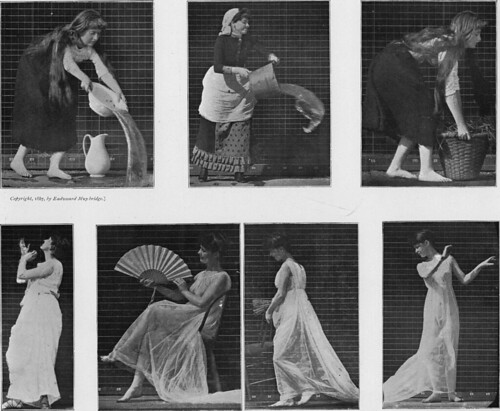

By the time of his final work, The Human Figure in Motion (1901), Muybridge had abandoned logical sequence almost entirely in favour of ‘miscellaneous’ or ‘various’ acts of motion. The connections between photographs are no longer progressive, or film-like; photographic movement is explored in these late works by dynamic page layout, by contrast rather than continuity.

Above: ‘Various Acts of Motion’, The Human Figure in Motion (1901).

Below: ‘Miscellaneous Acts of Motion’, The Human Figure in Motion (1901).

Marta Braun, Eadweard Muybridge (Reaktion Books, 2010).

See also ‘Action stations’ on the Eye blog, and ‘The mystery of frozen locomotion’ in Eye 75, both about Jonathan Miller’s ‘On the move’ exhibition earlier this year.

> 16 January 2011

Eadweard Muybridge

Tate Britain

Millbank

London SW1P 4RG

www.tate.org.uk/britain

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It’s available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop. For a taste of the latest issue, no. 77, see Eye before you buy on Issuu.