Tuesday, 12:00pm

2 June 2015

Retrogressive

An archive of historical, ‘aw shucks’ clip art shows a clipped version of history, says Steven McCarthy

One afternoon about fifteen years ago, my University of Minnesota office phone rang, writes Steven McCarthy. It was an attorney at law, claiming to represent The Gap, the clothing retailer.

He explained that his client was being sued by Minneapolis graphic designer Charles S. Anderson for copyright violation – it seemed that The Gap had reproduced what it thought was copyright-free clip art from a compilation of decades old illustrations published by CSA Images. Did I want to earn a quick $3000 as an expert witness by giving evidence in court?

‘Who’s Mr Anderson’s expert?’ I asked.

He: ‘Philip Meggs … heard of him?’

I declined, and not just to avoid battle with the late, venerable graphic design historian. I did not know enough about the case, and being on the right side of the issue ethically meant more to me than the money.

Fast forward to March 2015. Andrew Blauvelt, the Walker Art Center’s senior curator of design, research and publishing hosted an event unveiling ‘Minnesota by Design’, a new, online exhibit of Minnesota design. More than 100 designs, spanning well over a century, ranging from architecture to branding and products to books, are represented in a rich interface.

Post-It notes, Spam (yes, a designed meat food product), Henry Dreyfuss’s 1953 thermostat, Matthew Carter’s custom typeface created for the Walker Art Center (see ‘The space between the letters’ in Eye 19), the Twister game, April Greiman’s life-sized nude self-portrait and a modular logo for the Bahamas created by Duffy & Partners are a few examples from Minnesota By Design.

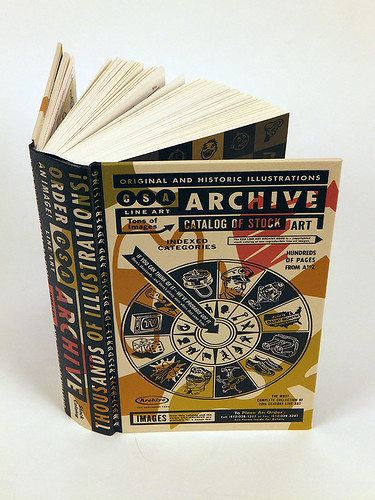

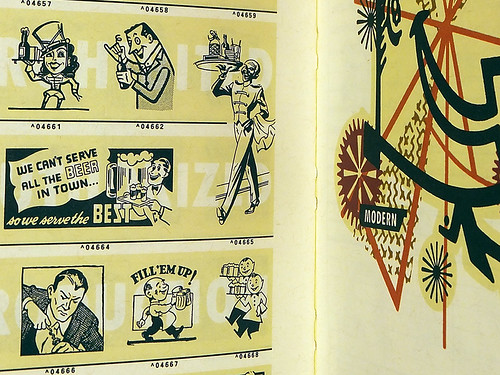

CSA Line Art Archive published by Charles S. Anderson Design, originally published in 1995.

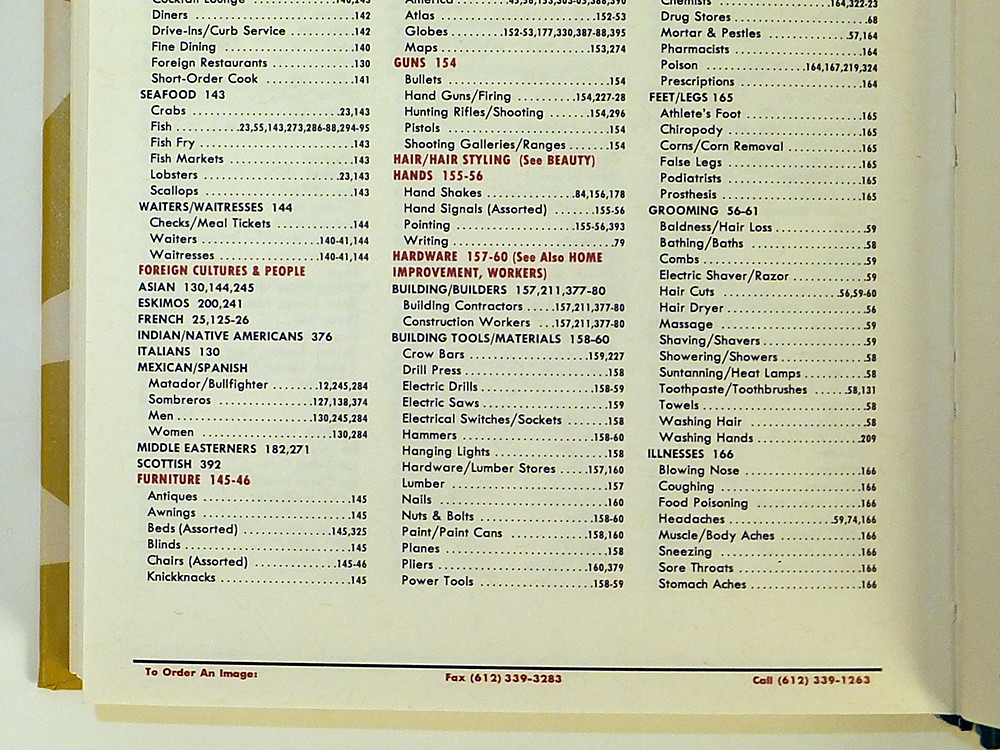

Top: An index page from the CSA Line Art Archive book.

One particular ‘Minnesota By Design’ item was also freely included in attendees’ treat bags: the CSA Line Art Archive book of advertising illustrations, originally published in 1995.

It is a teeming compendium of early to mid-twentieth century vernacular images, symbols and slogans, ‘a vast and ever-expanding resource of illustration inspired by the entire visual history of art, design, and typography,’ according to CSA’s website. Of the purportedly 7777 retro images the book offers, I wondered which one The Gap had used.

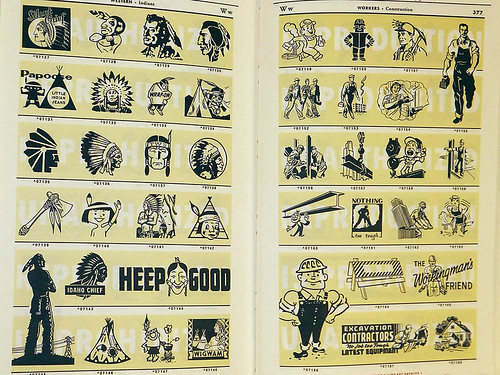

While posing as an encyclopedic catalogue of America’s ascendant popular culture, economic might and advertising prowess, Archive tells another story. The ‘entire visual history of art, design, and typography’ largely lacks depictions of non-whites. When other races or ethnicities are shown, like Native Americans (oddly indexed under ‘Foreign Cultures and People’), they are mostly in the stereotypical renderings once common to sports teams’ logos.

Apparently, African-Americans didn’t exist in the 1920s, 30s, 40s or 50s – or perhaps CSA Images edited out the era’s Little Black Sambo-like depictions for fear of offending. Wait, there’s image 04665: a smartly attired, quick stepping black waiter carrying cocktails. A couple of Asian and Hispanic people are depicted in the food section. The French are represented by chubby chefs in toques, and painters at easels.

Spread from Archive showing Native Americans and construction workers.

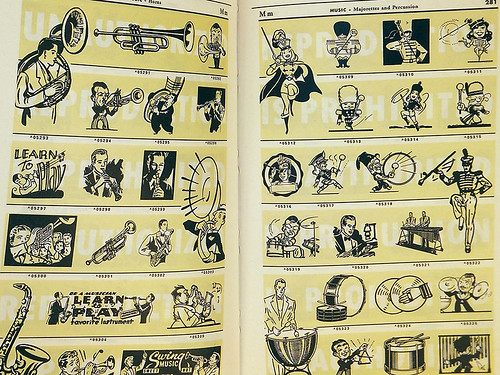

Line art illustrating wind instruments, percussion and baton-twirling majorettes.

Yes, those were different times. And when such images are shown as part of design history, captions and sources can provide context. However, CSA Images’ Archive is not a work of history, it is a work of commerce. Whether it sells a picture for any number of illustrative, graphic, packaging or publication designs, the book is an edited, redrawn, vectorised rendition of nostalgic images, often aesthetically pleasing eye candy. An ‘aw-shucks’ attitude prevails, wink wink!

But how does a book of select images – hardly the ‘entire visual history’ – frame contemporary perceptions of American life during the Great Depression, the Harlem Renaissance, the New Deal, the Second World War, the Baby Boom and beyond? That mid-twentieth century commercial illustrators depicted people from their socio-cultural vantage point is hardly news. But by 1995, the United States was a different place: legally integrated, socially aware, ‘politically correct’ and multicultural. Even then-president Bill Clinton was referred to as ‘our first black President’ by author Toni Morrison in a 1998 essay in The New Yorker.

When Abbott Miller wrote for Eye 14 in 1994 about stock photography, clip art’s slicker cousin (see ‘Pictures for rent’ in Eye 14), he stated that ‘US markets demand multi-cultural imagery.’ Does this suggest that art directors selecting that era’s photography are sensitive to issues of racial representation, while those licensing pictures from Archive are not? Or is it a matter of what is on offer?

Viewers of Archive might infer that America was a tidy, jolly, homogenous place until the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s interrupted the bliss. Whether viewers’ decoding of the images is unquestioning, informed, ironic or alienating, the book’s message (unintended or otherwise) cannot be ignored. I therefore retract my earlier assertion – in 2015, CSA Images’ Archive is a work of history, a culturally clipped history that cannot be overlooked with a wink and an ‘aw shucks’.

Spread from Archive.

Steven McCarthy, Professor, University of Minnesota

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.