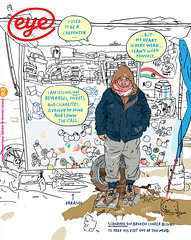

Winter 2016

Ardizzone at peace and in conflict

Edward Ardizzone’s experiences as a war artist gave an extra depth and toughness to his work

Like a number of his contemporaries, Edward Ardizzone (1900-79) aimed for a deliberate anachronism of style. Yet more than most of them, he made old methods work effectively to depict the modern world. For many British artists of his generation, there was bound to be a crisis brought on by the challenge of Modernism. At first sight, Ardizzone seems exempt from this, and did not appear to lose confidence or look for new directions, as did Edward Bawden and John Piper. Yet beneath the surface there was undoubtedly self-questioning and anxiety.

Ardizzone’s career had launched in the 1930s. Like Piper, he was a late developer and for a similar reason, that his father insisted on him following a ‘reliable’ career after leaving school. For Ardizzone, the path to becoming an artist was through the evening classes he attended at Westminster School of Art, and in 1927 he broke free of office life and began to earn his living as a graphic artist and painter. By 1939 he was a well known national figure, with his first three children’s books selling well and rapturously reviewed on both sides of the Atlantic, annual one-man shows in London galleries and inclusion in the art section of the British Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair. He owed much to the patronage of Kenneth Clark, who responded to his style, which combined elements of seventeenth-century classicism and a nineteenth-century taste for low-life subjects treated with benign humour. Clark’s enthusiasm for Ardizzone got him a place as one of the first Official War Artists, alongside Bawden, Eric Ravilious and Barnett Freedman.

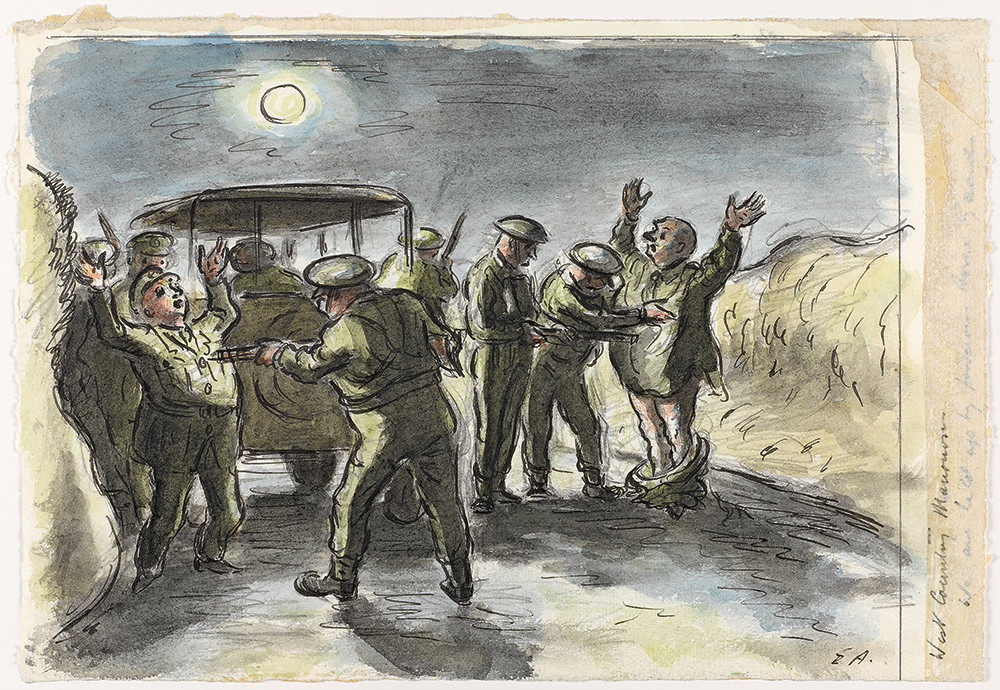

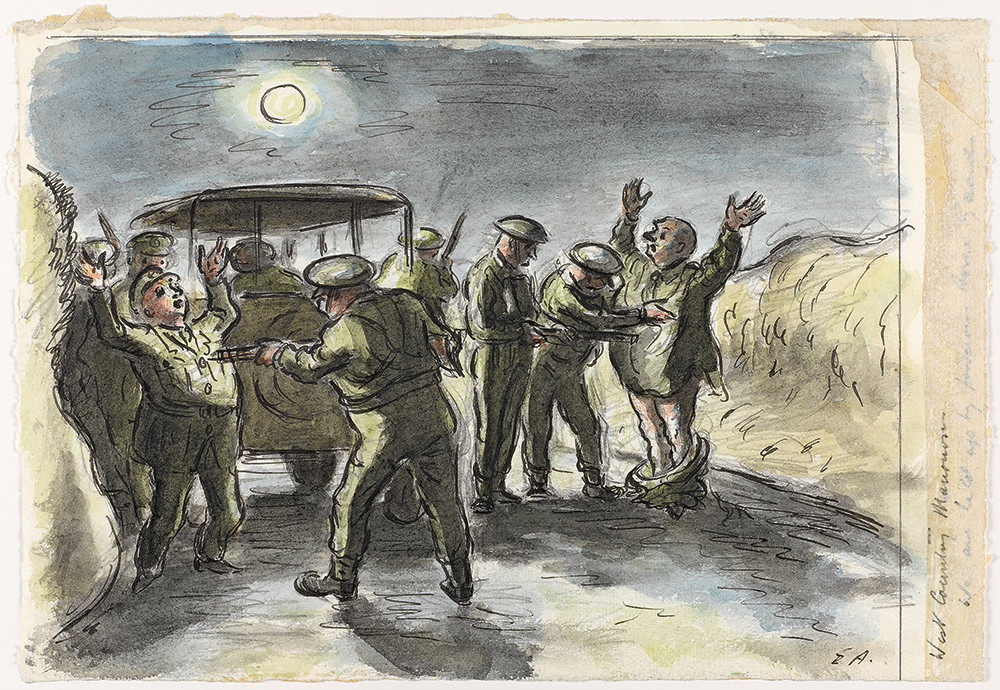

At the end of March 1940 he went out to France with the British Expeditionary Force, along with Bawden and Freedman – the trio were also protégés of Oliver Simon at the Curwen Press (see Eye 70). For most war artists, the pace of production and the unfamiliar subject matter was both a challenge and a stimulus. With Baggage to the Enemy (John Murray, 1941), Ardizzone became the only one of the group to publish an extended written record of his experience in the retreat from Belgium and France that ended at Dunkirk, and in this, with later diaries kept during the North Africa and Italian campaigns, we can listen to his responses to the experience. While generally expecting the worst to happen, as it did in the lead up to the evacuation at Dunkirk, Ardizzone maintained a cheerful attitude, possibly fortified by his undemonstrative Catholicism. He saw plenty of dead bodies and when he drew them critics sometimes complained that he was taking the war too lightly. They wanted the emotional wrench of Goya, but as Osbert Lancaster explained, not many modern artists were up to that level. Instead, in Lancaster’s classification, he gave them something more like Jacques Callot – a seventeenth-century printmaker who recorded the European wars of his time with graphic clarity.

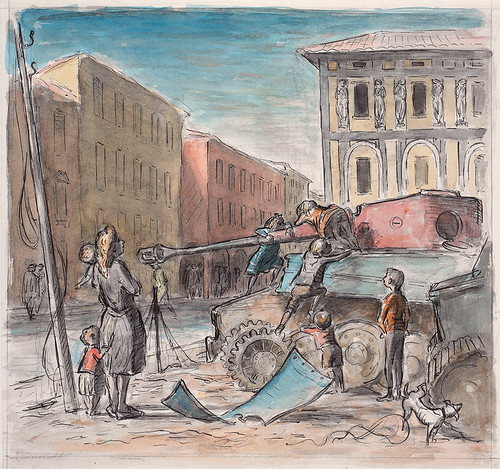

Ardizzone’s strength was in capturing moments of human action, often slightly comical ones, but his work matured as he moved away from the heat of the action in the course of the slow and painful campaign by British and American troops to break through the ‘Gothic Line’ established by the Germans across central Italy during 1944-45. Bawden, who had reappeared in this theatre of war, urged him to take the landscape as his subject rather than the sometimes conventionally-posed figure groups. This he did, in a few large paintings, such as A Battery Position in an Orchard of Young Fruit Trees in Snow, 1945 (Imperial War Museum), with a grid of trees stretching out of sight on the white hillside and no sense of spring in the air.

With his 400 war paintings completed, Ardizzone returned gratefully in 1945 to civilian life, teaching at Chelsea, Camberwell and the Royal College of Art, and resuming a hectic level of illustration for books, magazines and advertising. The postwar decade seems a glorious period for illustrators, since there were so many publications demanding line work for reproduction, a technique at which he excelled. It was during this time some of his most enduring illustration work was done, including Walter de la Mare’s Peacock Pie and Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress for Faber.

Children Playing on a Captured Enemy Tank in Forlì, 1945. Ink and wash on paper, courtesy Imperial War Museum, London. Top: West Country Manoeuvres: We Are Held Up by Ferocious Home Guards, 1941. Ink and wash on paper, courtesy Imperial War Museum.

The sweetness and nostalgia characteristic of Ardizzone’s work was toughened by a backbone of experience and keen observation during the war. He steered his students away from cliché and the fashionable styles of John Minton and Mervyn Peake. He shamelessly advocated copying, claiming to have learnt most from Rembrandt, Rubens and a nineteenth-century book on drawing trees. In a period dominated by Modernism’s quest for the new, not only his drawing technique but also his way of composing a scene like a theatre stage were being challenged –for example, by the use of close-ups in illustration, practised by Barnett Freedman.

In painting, Ardizzone exhibited with a group of mainly younger social realists, including Paul Hogarth, Carel Weight and Ruskin Spear, in shows such as Looking Forward (1952), curated by John Berger, and Looking at People (1955-56). In 1954 Ardizzone was invited by Ind Coope brewers to paint subjects of pub life for a touring exhibition. Given Ardizzone’s devotion to this subject matter (including The Local, 1939), he would seem a natural choice, but the picture he contributed is barely recognisable as his. A Quiet Morning in the Bar (1958) is dark and depressing. If this was Ardizzone’s attempt to place himself in the Kitchen Sink school, he must have recognised it as a wrong direction. The canvas never sold, and he returned to his familiar technique of line and wash and what Kenneth Clark called his ‘genial grotesque’.

In children’s picture books Ardizzone had published Little Tim and the Brave Sea Captain with Oxford University Press in 1936, and was encouraged to produce more books, as well as illustrating texts by Eleanor Farjeon, Philippa Pearce and other writers. He saw himself as an ‘Oxford’ man, but found it hard to go on producing more books about his most famous character. In 1956, Tim All Alone was a surprisingly dark story, beginning with a small boy returning home to find his house shuttered and his parents nowhere to be found. Ardizzone suffered depression at this time, and the book may have been its manifestation – as well as being his masterpiece, and recognised as such by the award of the first Kate Greenaway Medal.

Soon after 1960, Ardizzone proposed two books for Oxford that were more personal. His new editor, Mabel George, was promoting graphically bolder and at times faux-naïf styles, as practised by Charles Keeping, Brian Wildsmith and Victor Ambrus. She reluctantly accepted his Peter the Wanderer and published it in 1963. However Diana and her Rhinoceros was, in George’s view, poorly resolved. Protesting that he wouldn’t change a word, Ardizzone found a home for Diana at The Bodley Head, where Judy Taylor became his editor for the rest of his life. Diana was later acclaimed in 1979 as a feminist text (by Andrew Mann in Spare Rib). These episodes also speak of an internal crisis as Ardizzone reached the age of 60. Although his drawing style did not change, the imaginative quality of his stories was raised to a new level.

By the 1960s, he seemed better able to accept his role as an illustrator of reassuring stability; by the 1970s, English culture’s turn towards nostalgia meant that demand for his work never abated – he tends to be pigeonholed as a genial old buffer. However, his self-critical instincts saved him from ever fitting such a description.

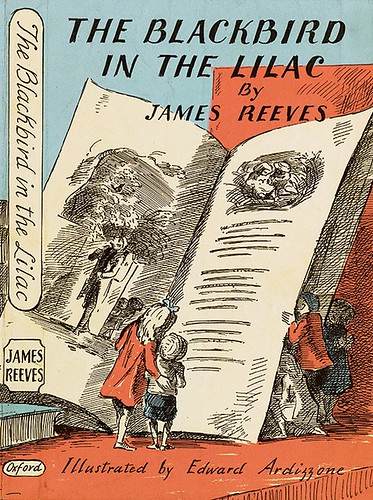

Cover and spine for The Blackbird in the Lilac: Poems for Children, Oxford University Press, 1952. Ardizzone numbered books by James Reeves, a ‘dear friend’ among his most pleasurable commissions.

Alan Powers is the author of Edward Ardizzone, Artist and Illustrator, published by Lund Humphries, 2016

First published in Eye no. 93 vol. 24, 2017

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 93 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.