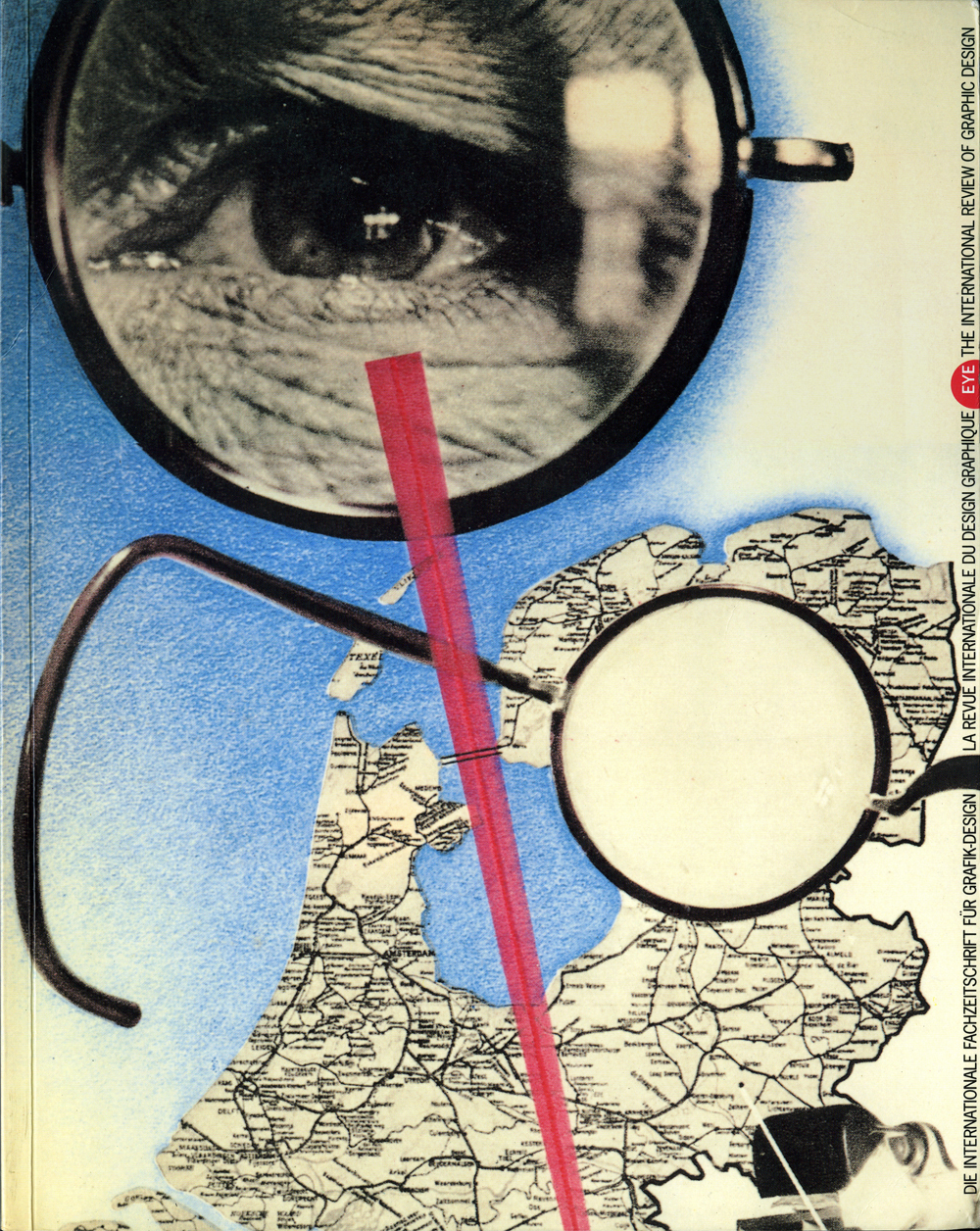

Autumn 1990

Cool, clear, collected

Blue Note designer Reid Miles and photographer Francis Wolff were a classic combo. Their covers have been envied, imitated, but rarely equalled.

In its ripest years – roughly from 1955 to 1965 – Blue Note Records represented a coherent phenomenon in which individually distinct elements combined beautifully to form a clear structure. This is the way in which one might describe a Blue Note track (recorded in Rudy van Gelder’s Englewood Cliffs studio) or a typical Blue Note album cover (photograph by Francis Wolff, design by Reid Miles) or – as I imagine it – the set-up in the company’s office, a small operation led by its founder and sole producer, Alfred Lion. So although Blue Note covers have today become an epitome of graphic hip – in their reissued form, or even more so in their now high-priced original states – they are no more than the visible manifestation of an organic whole.

If the development of jazz has been a story of Black people finding a voice in urban North America and spreading it across the world, then it was only following the gains won by the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s that this voice began to escape the racial-commercial constraints applied by White Americans and find its own place, unpatronised and relatively free of exploitation. In the 1950s independent companies began to give this music the respect it deserved: Savoy, Atlantic, Prestige, Riverside, Contemporary and Blue Note were among a host of often-tiny enterprises.

Recording has been crucial to the development of jazz, which cannot adequately be captured by written notation. And in this period recording took on an added importance in making possible the emergence of a new form of jazz culture. Long-playing records were also new, bringing the freedom of extended playing length and the possibility of making records as suites of pieces.

Blue Note stood out like a beacon even among the other independents: albums became projects with weeks of consideration behind them; rehearsal time was paid for. For the record covers themselves, descriptive notes, often analysing the music in some depth, were commissioned from critics. And Blue Note and most of the other independents resisted the cheap exploitation practised by the larger companies in their choice of cover image (anything as long as it did not relate to music and the more female flesh the better).

A key to understanding this aspect of Blue Note Records lies in the history of its founder and his business partner. Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff (who had been childhood friends) had come from Germany in the late 1930s. They would have known about human persecution, and they came to jazz from the unavoidable prejudices of White American culture. Though Blue Note covers have been criticised in retrospect as a take-over of Black culture by White style-merchants, they were in their day the best sign that this culture was at last being recognised by elements of White America as an essential component of the modern world.

These are some of the basic factors in the Blue Note phenomenon. But how to describe it more exactly? And how precisely to relate the qualities of the graphic package to the nature of the music? Pictorial covers came in with the ten-inch long-playing records which replaced 78 rpm discs. Blue Note began issuing LPs late in 1951 and their early covers, by various designers (including John Hermansader and Gil Melle), show that the company was looking for a style to match its new music. In 1956, Lion and Wolff discovered Reid Miles, the designer who was able to give them this style definitively: the graphics and the music now came together in (to quote Miles) ‘a marriage made in heaven’. And in Francis Wolff they had a photographer whose work was in itself graphic: a quality that seems to have been enhanced as his collaboration with Reid Miles got under way.

Applied to photographs, the term ‘graphic’ implies clearly defined marks, a contrast of light and dark tones and a willingness to leave undisturbed large areas of space or single tone. But in Blue Note, these qualities apply also to the treatment of photographs within the whole and to type, which becomes another element to be configured meaningfully into graphic form. In the best of these covers, the ensemble of image and test is greater than the sum of its parts. It is hard to describe these visual effects, just as (for similar reasons?) it is hard to pin down the qualities of, let us say, a piece by Jackie McLean: bounded by an explicit structure yet demanding each musician to contribute freshly, indelibly coloured by McLean’s rasping alto tone, by Billy Higgins’s forceful yet delicate drums.

‘Hard-bop’ is the usual label for the music that Blue Note mostly recorded in these years. A non-technical description might be: taut, unsentimental, often blues-based, played by a small ensemble. Oversimplifying, one might say that until that time, jazz had been shaped by great individuals: now the music developed a common approach, with skill and invention shared more widely across a broader base of players. This tendency was encouraged by record companies with a policy of fostering talent, of sticking with musicians through projects that might not show significant profit and of giving love and attention to every aspect of the recorded product. In these conditions, the music grew into what seems now to be the ‘classical’ period of jazz, before the mutations and dilutions brought on by the pop explosion.

There is a parallel explanation to be made in respect of the graphics of these album covers. Although they are the products of a particular individual, Reid Miles, and have Francis Wolff’s photographs as a vital ingredient, they are also the fruit of something larger. This is the culture of graphic design as it was by then developing in the US and above all in New York. The approach to type and image described here is actually the common – perhaps ‘classical’ – style of that time and place. It was worked out in magazine design, in advertising, in packaging and in other areas of corporate design. It fed on a lively photographic culture and on a good stock of typefaces in the printers and reproduction houses – especially of the American sanserifs. Blue Note covers hardly use illustration (though some early Warhol drawings can be spotted on a Johnny Griffin record and on two early Kenny Burrells); perhaps the ‘manufactured’ nature of type and photography was more appropriate to the hard edges of much of the music.

Blue Note covers were produced on low budgets – Reid Miles remembers that his fee was ‘50 bucks an album’ – and most look to have been done very rapidly, some very rapidly indeed. On his own account, Miles was never a real enthusiast for this kind of jazz; he worked from a simple brief from Lion which summarised the character of the album. But the fact that Miles was not completely involved with the record content may help to explain the splendid sense of certainty that many of these covers have: the product of going straight for the simple, brave answer, without the problems brought on by too many possibilities. Here the use of space plays its part: in some of the black and red covers, white seems to become a third printing, a positive component. Varnish applied to the fronts of covers (which in earlier years were often printed letterpress) contributes to the incomparable object-quality of the originals. Later, perhaps when budgets became larger, four-colour process printing was used, but these covers look weak by comparison. Turning to the other side, recording details and ‘liner notes’ were given a standard, sober treatment, saving design time and paying appropriate regard to the music. And the cover was made from thick board, which seemed to say: this music is a unique creation, treat it with respect.

Blue Note Records came to an end, in spirit if not quite in name, when Alfred Lion sold the label to Liberty in 1966. Reid Miles went off into photography and television, several hundred covers on from the time when Art Blakey, Horace Silver and all the others were just starting to create a ‘canon’ of modern music, album by album.

From the early 1980s onwards, Blue Notes have been re-issued in floods and ebbs. Emanating from the US, France and Japan, they must have reached most corners of the world by now. Just as the re-pressing of the vinyl discs (or transfer to tape or CD) loses sound definition, so the reproduced covers lose some of the subtleties of the originals. But these losses can be lived with; the principle of multiple reproduction wins out. It is nice to think of so many modest master-works of mid-twentieth-century culture still in circulation.

First published in Eye no. 1 vol. 1, 1990

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.