Winter 2006

Emotion graphics

Is character design a fount of rich, contemporary visual codes . . . or just a cop-out for over-stressed kidults?

For those who care, ‘character design’ is undeniably cool. These abstracted little beings, with names such as Seeker, Goner, Bunniguru and Meeghoteph, make a direct appeal to our emotional attention. And judging by their visibility in design bookshops, MTV, art, street art and advertising, their creators – illustrators and designers – are in the process of making a new global language. In our image-saturated environment this strategy for bypassing the written word has become hugely popular on the frontline of design, illustration and art.

Pictoplasma has been charting and championing the growth of this new phenomenon of figurative expression since 1999. This Berlin-based group is defining a new sub-field within design and illustration: it has published three collections of characters, and holds an online archive of characters that contains more than 6500 specimens.

The Second Pictoplasma Conference (11-14 October 2006) brought together designers, animators, illustrators and artists who are involved with what the organisation claims is ‘a new breed of character design’ and the ‘birth of a language beyond all cultural boundaries’. Intent on ‘giving characters life’, the conference literature featured photographs of humans dressed as graphic characters such as Helper and Leaflet.

A beginner’s guide to this sometimes bewildering graphic universe might feature Hello Kitty, Rob Reger’s Emily the Strange and James Jarvis’s In-Crowd. Contemporary character design, abstracted and reduced to the essentials, samples and remixes existing visual codes. Disney characters are not welcome here; nor are the alternative comics characters of the past century, such as Fritz the Cat or Tank Girl. Pictoplasma is defining the perimeters of a new genre. Jamie Hewlett may make the Design Museum’s criteria (as winner of the ‘Designer of the Year Prize’) but his characters do not appear in the Pictoplasma archive. Lars Denicke of Pictoplasma explains: ‘We are looking for iconic characters that gain their meaning through their design, its reduction and anthropomorphic appeal and through their setting, and not so much through a genre and its narrative implications.’

Character designers work across all media and disciplines: they are unconcerned about any traditional distinctions between art, design and entertainment. Fred Deakin and Nat Hunter from Airside define themselves as working entertainers, and their alien life-form character Meeghoteph (which has featured in an interactive installation at The Big Chill music festival) provides evidence of a character spilling into other dimensions.

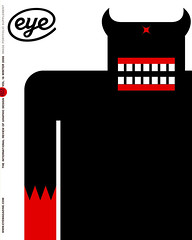

Motomichi Nakamura, Punto Zero, 2003, on the cover of Eye no. 62.

Gary Baseman, named one of the ‘The 100 Most Creative People in Entertainment’ in America by Entertainment Weekly, labels his practice ‘Pervasive Art’, by which he means to produce art in every outlet possible – galleries, print, television, film, lecture halls and even commerce. Such fluidity enables artists to weave their vision deep into the fabric of contemporary life. The work in this field encompasses illustration, publication design, product design (calendars, diaries, bags, purses, stickers, wallets, T-shirts, hoodies, jewellery), toys, commercial animation, music videos, films, computer games, painted interiors, paintings, performance art, public interventions, and installations. It’s the characters that bind these diverse media output and worlds together. Designers such as Brooklyn-based Motomichi Nakamura manage to juggle various roles with grace: his stark, three-colour (red, white and black) characters move from games and art installations to MTV ads and VJ sets. Nakamura’s work is often brutally aggressive. ‘As long as you have a happy ending it can be as violent as you like,’ he says. In contrast to this, the characters of Akinori Oishi (Japan) exist in innocent computer games where there is no enemy or death. Oishi’s sketchbooks of intricate drawings are the cornerstone of his practice, and many of the designers / artists at Pictoplasma 2006 showed an admirable commitment to hand-drawn work.

Several designers, including Baseman, Nakamura, Oishi, Airside, Tim Biskup, François Chalet, and Friends With You, have been accepted as fine artists in some quarters. Baseman’s work is in the permanent collection of the National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC and the Museum of Modern Art in Rome. Airside is presently exhibiting an interactive installation at the 2006 Liverpool Biennial commissioned by National Museums Liverpool.

The Berlin conference was essentially an event for creators of characters, with an emphasis on creative strategies and production methods. Several presentations revealed the personal relationships that many artists have with their characters. While some see their characters as a means to an end, a device to answer a brief, for others they represent private notions and narratives, embodying ideas in the personal mythology of their creator. Amsterdam-based Fons Schiedon states that he is not an artist, and the characters exist for the purposes of working in an animated short story. At the other end of the spectrum, Tim Biskup explains how his characters Goner and Helper are attempts to translate feeling. Rilla Alexander of Rinzen describes her relationship to the character Seeker as an embodiment of her feelings about immigration from Australia to Europe. And Nathan Jurevicius struggles with his role as a parent and creates Scarygirl.

A high degree of subjectivity is made possible by production methods that have given designers the opportunity to set up their own toy companies, publishing labels and animation studios. By selling work directly from their own sites, they reduce the layers of mediation between producer and consumer, and this independence has fostered the creation of idiosyncratic work, full of powerful and personal narratives. Characters can express emotional content in an efficient manner. The process of reducing characters to their essentials increases their expressive ability. Such abstraction also increases identification. Codes are learnt and manipulated in order to communicate ever more subtle data and social signals: characters draw attention to a visual language in flux.

Yet this new movement is open to charges of decadence. Does character design merely represent the self-indulgent scribbling of adults clinging to childish toys – silliness that signals a huge retreat into the imagination? During the conference’s best panel discussion, on ‘body’, Sam Borkson and Arturo Sandoval of Miami-based Friends With You (having shed the costumes they were wearing earlier), discussed the relation between their design work and magic, linking their practice to art, ritual and spirituality. Some might find plastic toys as a spiritual tool a bit of a stretch, but the audience, entranced, let them get away with it.

A presentation on the ‘aura photography’ of characters revealed that there are some people who are taking the field into uncharted (and somewhat bizarre) territory altogether. Friends With You claimed that in a culture dominated by gangsters (as it is in Miami), a retreat into innocence is a valid response. Several delegates defended the notion of the ‘kidult’, arguing that as long as the expectations of adulthood are as fierce as they are in America and Japan, a counterculture emphasising innocence functions as a critique of the dominant model. Whether such ‘kidulthood’ will challenge assumptions or simply offer another escape route remains to be seen.

Though the final panel topic was ‘narration’, there was no discussion of how narratives are built through systems of signs, no mention of semiotics or communication theory. If characters are, as Pictoplasma claims, a new international visual language, the tools we use to analyse the way language works will surely help us learn how characters work. Semiotic theory would give this movement a way to understand how meaning is constructed in the worlds of Rusty, Scarygirl, Hot Cha Cha, Emily and their friends. But the characters are doing what semiotic theory could never do on its own, which is to establish a precious and instantaneous emotional bond between each creation and its audience.

Jody Boehnert, designer, London

First published in Eye no. 62 vol. 16 2006

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.