Winter 1993

If the face fits

Well dressed magazines wear tailor-made fonts. Eye talks to three of the most sought-after names

Why, when foundries everywhere are producing inexpensive digitised fonts, do American magazine designers feel the need to create their own? Is it because reading in the US is now more of a chore than a leisure activity, so magazines are becoming more colourful and decorative as designers compete with MTV? In a market where many magazines are covering the same subject jostle for the same advertising dollar, it would make sense that art directors should seek new ways to make their product stand out. Or are they just indulging their egos?

‘Yes,’ says Rolling Stones art director Fred Woodward with a grin, ‘but in facts it’s not so glamorous.’ Hiring type designers and letterers came from wanting to work bigger and bigger. ‘We would blow up type on the Xerox machine, but it would distort and we needed someone with good hand-skills to make it perfect. It also grew out of trying to use faces we thought were a bit rare.’

‘Having custom fonts is not new. That’s where Century and Times came from,’ says Roger Black, who besides having been head of design at the New York Times and Newsweek has been a constant force behind the revival of extinct metal faces. ‘Besides trying to achieve a unique look, having a custom face is worth it because you can fine-tune it to fit your printing capabilities.’

Woodward and Black are ubiquitous names in this small world of type centred in New York. Woodward represents the avant-garde of commercial magazine design that will be copied by everyone else a couple of years later. His focus is specific to the story or issue at hand. Black’s scope is wider, and he and his studio have redesigned large, well-established magazines and newspapers, not only in the US but in Latin America and Europe as well. Working closely with them are type specialists Dennis Ortiz-Lopez and Jonathan Hoefler, who operate one-man foundries in New York, and David Berlow at the Font Bureau in Boston.

Dennis Ortiz-Lopez

Dennis Ortiz-Lopez drew his first professional alphabet in 1967 and has been an ornamental type designer for New York magazine art directors since the 1970s. if there is a need for special lettering on a cover, a display face for a one-off section, or a redesigned logo, the solution is simple: ‘Call Dennis’.

Fred Woodward explains how their connection started. ‘We would start letters out of small books from the flea market, even jut for a headline, and then get Dennis to draw up the alphabet and fill in the gaps.’ In those days a fancy headline was as far as they got, but in more recent – that is, digital – times, if the designers at Rolling Stone decide that the face Ortiz-Lopez is drawing up for a custom headline ‘had legs’, they will commission him to design the entire alphabet. Thus were born faces such as Woodward Long and Tall and Sinead Stoned And Pointy, both thing and graceful nineteenth-century-inspired fonts that are perfect for editorial since they can be run large yet still fit in a lot of characters. Typefaces such as Anderson Gothic were inspired by old type catalogues.

Working on New York’s Upper West Side in a small living room crammed with computer equipment, Ortiz-Lopez, in shorts and with a shaved head, says that he rarely originates fonts without a commission, though sometimes he will finish an alphabet he likes himself. ‘I’m only in it for the money,’ he says wryly, ‘so I usually only draw what people pay me to do. No greed, no ink. But if I draw a headline of say 17 letters, and then a week later I like to font, I’ll finish it up. Most of my catalogue came from that.’

His catalogue is a collection of fonts he has drawn since he started using the Macintosh three years ago. It includes a portfolio of logos and exclusive fonts as well as a list of commercially available faces. Ortiz-Lopez is quick to point out that all of them were drawn directly on to the computer, without any scanning of originals. By his own estimate he has drawn about 100 alphabets in the last three years, with many extra add-on faces sporting ring shadows, highlights, tinted layers and the like. Most are titling faces with no lowercase, Campaign ’92 Initials was commissioned by Greg Leeds, art director of special sections at the Wall street Journal, for use in a report on last year’s Clinton-Bush campaign. The typeface was developed from Stokler, a fat nineteenth-century wood poster face, to which were added stars, stripes, an outline and a drop shadow.

Other fonts Ortiz-Lopez has produced for magazines include headline faces for Premiere, Men’s Journal, Us, New Woman, Self and Family Life. He has also drawn the logos for Metropolitan Home, Sports Illustrated, People, Texas Monthly, New Woman, Travel & Leisure, Self and new magazines In Style and Family Life. He has been commissioned by book publishers and video companies and is currently working on an alphabet logotype for the Milwaukee Braves baseball team.

Jonathan Hoefler

If Dennis Ortiz-Lopez is the hired gun of the ornamental display type world, Jonathan Hoefler is the reincarnated monk of text type. His booklet Every Art Director Needs His Own Typeface promotes the two major strands of his work: the studied redrawing of old faces for modern technology, for example a new cut of Bodoni, and new interpretations of old type designs such as his Hoefler Text. Hoefler Text, as descrived in his booklet, is a combination of Garamond No. 3 and Janson Text and includes four fonts ‘complete with modern and quaint ligatures, small caps, swash caps, terminals, alternates and fleurons: all in all, a total of 508 characters with 1,866 kerning pairs.’ Jonathan Hoefler is serious about his work.

‘Jonathan brings typefaces to our attention. He’s our type historian,’ says Fred Woodward. Hoefler has recently designed a series of fonts for interchangeable use in Rolling Stone, where the art department deciced to redo the type format for each issue rather than just for specific features. The faces are all variations of Ziggurat, a fat slab serif that Hoefler then translated into a Latin wedge serif and a Grecian and wooden-look sans serif. They all share the same character count so they can be easily transposed.

Hoefler was also commissioned to draw a series of nineteenth-century poster-like Gothic headlines for art director Steven Hoffman at Sports Illustrated. But sometimes the faces’ function is transformed. ‘They were originally supposed to be all set at 36 point. Now they’re all over the place, even in captions at 10 point. It’s really scary,’ says Hoefler, a slim young man of 23 with trendy tortoiseshell glasses. He tries, not always successfully, to educate his clients on the more arcane aspects of type. ‘Recently someone form Rolling Stone called me up to ask why I had named their new face Ziggurat. I began the tedious explanation of how at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution advertising type was invented to promote consumerism and there was a lot of excitement at the time about Egypt so they began calling slab serif type Egyptian, and so…They said, “Yeah, yeah, OK Jonathan, must go”.’ One of his more visible jobs is the Bodoni he drew for Fabien Baron at Harper’s Bazaar. As Hoefler describes it, ‘Fabien said, “I want you to draw me Didot Bodoni”. So I said, “Well, do you want Didot or Bodoni, because Didot was an eighteenth-century French type foundry and Bodoni was Italian?” Fabien said “Whatever”.’ Hoefler now looks at his Didot in Harper’s Bazaar and realises, ‘It’s condensed 80 per cent. What are they thinking?’

Hoefler started work on magazine development for Roger Black’s studio in 1989, while attending Parsons School of Design. He soon dropped out. ‘I found I could make up a fake annual report for some second-rate art director from the 1960s at school and get lousy advice, or make up real magazines for Roger and hear what the client had to say. It wasn’t a difficult choice.’ Three years ago he went freelance, and he has been on his own ever since. ‘It’s been one long rollercoaster of type,’ he says, starting with his first font for the Chicago Tribune, a Grotesque 79 done for the Font Bureau.

Hoefler’s studious approach to type history brings him to other mediums than the Macintosh. His business card is set in metal, and he is toying with the idea of learning stone-cutting to give him an understanding of the roots of modern type. Besides magazines, his biggest clients are Adobe and Apple, for whom he has designed a TrueType GX font, due for release this spring.

David Berlow

While Jonathan Hoefler and Dennis Ortiz-Lopez are asteroids in the digitised font universe, Font Bureau has grown to be a proper planet. Back in the early 1980s, David Berlow was working was a type designer at Linotype and later at Bitstream with Matthew Carter. ‘Roger Black would come through on a strafing run, trying to get custom fonts for this or that magazine. It was too expensive and too laborious to do them, so we just told him to forget it. Then I started with the Macintosh in 1986. Designing type with it was akin to sculpting a bus through a porthole. Later we got a Mac II, Fontographer, a big monitor and a laser printer, and suddenly designing new type seemed easy. So the next time Roger came through we were ready.

‘At that point, Matthew suggested we do a custom face. So we did Belizio, something like Egiziano, for Roger, who at the time was working for California magazine. I began to think it was time to do a business plan.’

Berlow went off to work on his own, and Black offered to be his partner. They leased Macintosh equipment and the new team went on to design the fonts for Smart magazine, some for the New York Times, and the main fonts for the redesigned San Francisco Examiner. By 1990 they had 13 faces that had outlived their exclusively contracts and Gone Bureau was able to start selling them commercially.

Now Font Bureau, made up of Black, Berlow, his brother Sam and an assistant, employs 20 freelance type designers. ‘We produce about 230 faces a year, a third of which are digitised versions of typefaces found in old specimen books, a third brand-new designs for both retail and custom fonts, and a third specific client requests,’ says Berlow. ‘An example of a client request is the New York Times, which is now in the process of converting from Autologic to PostScript. We are about halfway through redrawing the 50 faces the paper uses.’ Font Bureau has also been hard at work creating a new text face for Newsweek. ‘It is based on the nineteenth-century Edinburgh, or Scotch Roman from the Miller Foundry,’ says Black.

‘There is an advantage to producing custom fonts,’ Black explains. ‘When someone like Matthew Carter designs a commercial font, he is trying to imagine what people want. In our case we known exactly what they want, and the design is clear and focused.’ Art directors are constantly consulted. ‘And they go serif by serif,’ moans Berlow.

Font Bureau is perhaps best known for its family of Grotesques. A few years ago it was impossible to look through an American magazine without seeing Franklin Gothic everywhere. Today, ‘People can’t seem to get enough Grots,’ says Berlow. ‘It’s the face that’s eating America now.’ Magazines that have bought custom Grots include Entertainment Weekly, PC Week, Esquire and Smart Money, as well as the newspapers El Sol and the Chicago Tribune.

‘Reproduction is the most important thing about publication custom fonts,’ says Black. ‘It’s a production problem rather than design. For instance, Times may be a great letterpress face but it doesn’t work well offset. We just did a version of Palatino for Playboy because the text wasn’t matching on their gravure and offset sections. Newsweek goes to ten printing plants, so we are still in the process of fine-tuning the Scotch Roman. We can adjust our design to whatever printing and paper a publication uses. Many newspaper people flounder around trying to make their typefaces legible by changing the printing or the plating, but with custom faces we can tune it exactly. After all, the whole idea is to get people to read this stuff.’

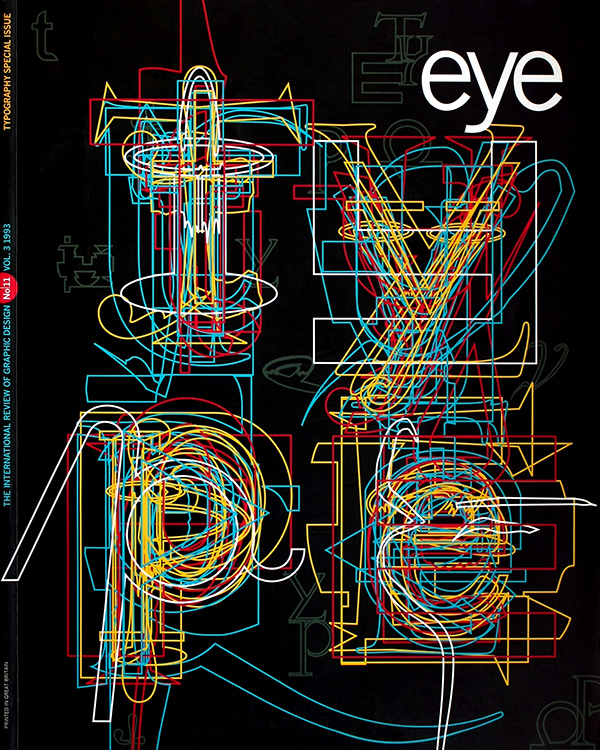

First published in Eye no. 11 vol. 3 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.