Spring 2019

Last man casting

Rainer Gerstenberg is one of the few people in the world to cast foundry type, keeping alive a craft that was developed more than half a millennium ago

A visit to the top floor of an old factory building in Darmstadt, half an hour south of Frankfurt am Main, Germany, is like time-travelling to an era not so long ago. Since 1997, Rainer Gerstenberg has been casting metal type there, surrounded by heavy machinery, hundreds of type cases, even more matrices, all covered in a fine layer of grease and molten lead. These objects represent the remains of a tradition that began with Johannes Gutenberg, inventor of the ground-breaking hand mould, a device that could cast letters from a matrix even in the 1450s. (Prints were already being made from movable metal type on the Korean peninsula, more than 70 years before.)

An alloy of lead, antimony and tin is pressed into an instrument containing a matrix that slides back and forth, ejecting letters that are used for letterpress printing. ‘Foundry type’ describes metal sorts that are used for setting text by hand, as opposed to letters cast from typesetting machines, some of which set and cast an entire line of type at once (which are melted down again after printing).

Many consider the quality of foundry type (which is meant to last forever) superior to that of line casters (e.g. Linotype or Ludlow casters) as more attention can be paid to kerning of overshoots and to the overall finish of a single letter. Gerstenberg casts foundry type from original machines that belonged to D. Stempel (Frankfurt, Germany) and Haas (Basel, Switzerland), two of Europe’s largest and most influential type manufacturers of the twentieth century.

One afternoon I sat down with Herr Gerstenberg over coffee and cake and he told me the story of how he took possession of this now antique equipment and how he continues to cast metal type in the 21st century. His kind and charming nature comes with a warm Hessian dialect. He is a very knowledgeable man, with decades of experience in the field; his hands show traces of years of heavy physical work. Is it safe to say that this is the last type foundry in Germany I ask? ‘The last one in Europe,’ responds Gerstenberg with a mix of pride and regret.

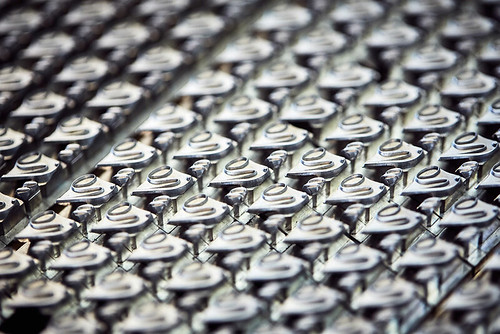

Rows of Künstler-Schreibschrift (artist’s cursive writing), first designed at Stempel as early as 1902, extended by Hans Bohn in 1960.

Top. Since 1997, Rainer Gerstenberg has been running his type foundry at the Haus für Industriekultur in Darmstadt. He is surrounded by 43 machines, most of which cast type from Stempel, Haas, Klingspor, Deberny & Peignot, Nebiolo and others, at a range of 4-72 point type size.

Photographs by Norman Posselt.

Negotiations and typefaces

In 1961, Gerstenberg began his three-year apprenticeship at Stempel’s type-casting department. In the previous decade, Hermann Zapf (1918-2015) had left his mark on the foundry by designing the popular typefaces Palatino (1950), Melior (1952) and Optima (1958). For the next 22 years Gerstenberg worked at Stempel as a type founder, casting Zapf’s typefaces as well as many others, including Garamond, Janson, Diotima, Neuzeit Grotesk and even more typefaces on licence from Haas, such as Helvetica. While Stempel’s machines can only cast their own type exclusively, Haas’s casters process matrices from other manufacturers.

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, Stempel had an exclusive relationship with the Mergenthaler Linotype Company, essentially as the only producer of matrices for the Linotype line-casting machine in Europe. As a result of this deal, many Stempel typefaces were available for both hand- and machine-setting. In 1941, the Berlin-based subsidiary of Mergenthaler Linotype became the majority stockholder of Stempel. The company did not become involved in the development of phototype-setting equipment until the late 1970s – very late, compared to their competition.

Overnight decision

One morning in 1985, Gerstenberg and his co-workers learned that Linotype had purchased Stempel’s type department. As he recalls, the liquidation of Stempel was an ‘overnight decision’. Because he was chairman of the works council and a member of the supervisory board of employees, Gerstenberg was involved in the negotiations that followed.

Against the will of Stempel, who were slight majority shareholders in Haas, Gerstenberg started negotiations with Haas. Agreements were made that Haas would remain independent, because ‘Linotype had no interest in acquiring Europe’s oldest type foundry’, as Gerstenberg remarks sarcastically – although they eventually did in 1989! Haas sold their equipment to Walter Fruttiger, with whom Gerstenberg and two other partners founded two companies that continued the production and distribution of foundry type from Stempel, Haas and other related foundries such as Klingspor Bros. and Deberny & Peignot in a typographic world that quickly turned digital.

The foundry’s new home

Instead of remaining in Frankfurt, the machines moved to Darmstadt, a Hessian town of approximately 150,000 people. Between the technical university of Darmstadt, Heidelberger Druckmaschinen (a leading mechanical engineering company that specialises in printing products) and several sponsors such as the local newspaper Darmstädter Echo, a museum was formed, the ‘Haus für Industriekultur’. It moved to an old factory building (a fitting site) in 1997 and became the type foundry’s new home.

Darmstadt is perhaps best known as a centre of ‘Jugendstil’ and its artists colony founded in 1899 by Ernst Ludwig, the last Grand Duke of Hesse (1868-1937), in the Mathildenhöhe district. It features Peter Behrens’ (1868-1940) architectural debut – his own house – as well as several houses by Joseph Maria Olbrich (1867-1908), but most notably the prominent ‘Hochzeitsturm’ (or wedding tower, which Olbrich designed to mark the Grand Duke’s marriage).

During a final meeting, Linotype signed an agreement with Gerstenberg, that he could cast type without paying royalties to the company. The intellectual property of Stempel’s type designers was transferred to Linotype and was tied to their digital fonts. This decision secured Gerstenberg’s business model for the subsequent years. Shortly before his official retirement, just a few years ago, Gerstenberg had a dispute with Fruttiger, and lost his company. Eventually he bought it back from his former business partner and today he runs it on his own, supplying about 30 to 40 clients, with an increase in the American letterpress market.

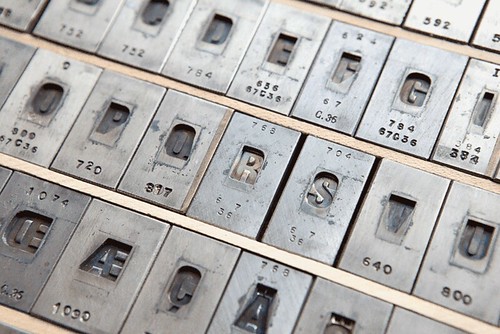

Matrices of Univers 67. This bold condensed weight is one of 21 styles in an impeccable system of widths and weights, designed by Adrian Frutiger, released by Deberny & Peignot in 1957. Photograph by Max Zerrahn.

A million matrices

Shelves packed with metal type on the top floor of the factory building are mere appetisers to the main dish in the basement: a store of around one million matrices from the major European type foundries. Each one is numbered (Stempel’s old inventory is still in use) and recorded digitally so that it can easily be accessed for casting. These include Nebiolo’s matrices, which were acquired in the late 1990s. Gerstenberg has roughly ten tonnes of cast popular Stempel types in storage. However most of his American clients ask for more unusual designs from Klingspor, and are generally interested in any type that is not available from Monotype casters.

Gerstenberg has two main worries. He has offered the museum all of his equipment as a gift in case anything happens to him. He says the museum turned down his proposal and expects him to leave the floor in a ‘well swept condition’. ‘That’s the deal’, Gerstenberg reveals, but acknowledges at the same time that without successor arrangements – and therefore no one to operate the machinery – the foundry would just be a dead museum.

In recent years he has reached a cooperation agreement with the Klingspor Museum in Offenbach that someone should be trained to become a teacher for demonstrations – not only of castings, but also of typesetting and printing sessions – a collaborative effort that involves the printing museums in Leipzig and Mainz. However a candidate has not yet been appointed.

Well into retirement, Gerstenberg still goes to work every day from 6 to 12 am. His daughter Angelika Wade assists him from time to time. When asked how much longer he plans to continue to cast type, he responds: ‘As long as I am fit I will do this. This isn’t work, this is a vocation. I have grown together with this place and I couldn’t do it any other way.’ Others might go to Mallorca, lie by the sea and get a tan. Herr Gerstenberg goes to his type foundry.

Thanks to Rainer Gerstenberg for the conversation, and to Norman Posselt for joining me on the journey to Darmstadt.

Gerstenberg does not have an apprentice, but in recent years he has been assisted by his daughter Angelika Wade, seen here calculating the quantity of letters they need to cast. Photograph by Norman Posselt.

Ferdinand P. Ulrich, typographer, type historian, lecturer, Berlin, Germany

First published in Eye no. 98 vol. 25, 2019

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 98 looks like at Eye Before You Buy on Vimeo.