Summer 2001

Marked by time

Two catalogues reveal much about stencil-making in Germany and the US in the mid-twentieth century, while offering clues to the industry's future in the decades following their publication.

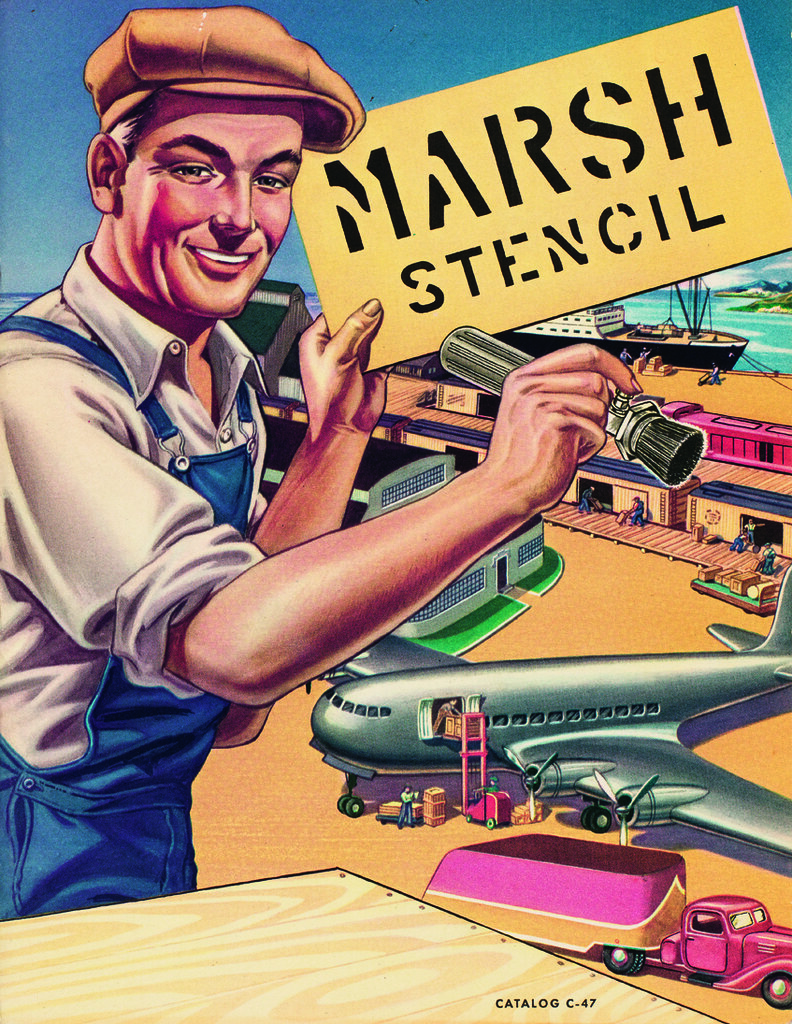

The two catalogues shown here, advertising equipment for stencilling letters and marks of various kinds, straddle the Second World War. One is German, issued in the late 1930s by the Sächsische Metall-Schablonen-Fabrik (Saxony Metal Stencil Factory) located in Zwenkau, a district of Leipzig. The other is American, made in 1947 by the Marsh Stencil Machine Company of Belleville in southern Illinois. Together they illustrate the stencil-making industry in the middle of the last century, if in quite distinct ways and in rather dissimilar circumstances.

Marks of ownership and identification printed on personal possessions, commercial appurtenances, sign boards and buildings have long been the domain of stencilling. At a small scale, these might be elaborate heraldic devices stencilled as book-plates, or delicately intertwined monograms first stencilled on handkerchiefs or pillowcases and later worked over with embroidery. Stencilled signatures were used at the close of letters, in guest-books or under the collar of a shirt giving the identity of its owner so as not to be lost in a communal laundry.

Modest applications such as these were typical of nineteenth-century stencilling and were joined by the more robust ones of commerce and industry: for armaments and dry goods packaging, shop signs and rogue advertising, seed sacks and prison uniforms. These remain familiar to us today.

The catalogue of the Sächsische Metall-Schablonen-Fabrik is at once ordinary and slightly unusual in its representation of stencil-making in the 1930s. The company was established in 1886 and after more than 50 years it had remained a specialist in the field, supplying stencils for commercial and industrial purposes like those just mentioned. While in Germany the stencil specialist was probably common, this was often not the case elsewhere. Entrepreneurs in Britain and North America, who in the mid- to late-nineteenth century began as stencil makers, usually expanded their operations into other kinds of marking, from rubber stamps to variously formatted, hand-held printing devices whose characters could be re-arranged like letterpress types.

The Sächsische Metall-Schablonen-Fabrik was typical, however, in its range of stencil products, from single-character-per-plate sets advertised for shopkeepers, complete with ink and a brush, to larger, custom-made plates of words, symbols and trademarks. The style of letter used was most often a modern face roman in the Didot manner. This reflected a regional preference (still evident today) in the basic, or standard, stencil letter: the modern face roman was prevalent in continental Europe. In Britain and North America, makers were partial to clarendons and ionics (along with sans serifs) and the modern face roman was comparatively rare.

Elsewhere in the catalogue are found more obviously German stencil letters, derived from the DIN 1451 and DIN 16 sans serifs, and from Deutsche Schrift (Rudolf Koch, 1910) and National (Walter Höhnisch, 1933), two types popular during the Third Reich. Broken-script (or more commonly ‘blackletter’) types such as these seem especially well suited to stencil adaptation, their construction already tending toward separate elements. But they acquire a retrospectively sinister effect in the stencil plates cut for the regional civil services of the National Socialists, who probably generated a steady demand.

Where the Sächsische Metall-Schablonen-Fabrik generally preserved stencil-making that with copper, brass or zinc produced objects both of utility and (when seen and held) of industrial art, the Marsh Stencil Machine Company was, by significant contrast, less interested in the stencil per se and more in its easy customisation and use. Marsh’s stencil machines removed stencil-making from the specialist, placing it instead in the hands of the worker on the shop floor. There stencils could be produced quickly and without any special skills, the machines ensuring at least a degree of proficiency in details such as letter and line spacing, even if the sans serif characters were relatively mundane. The use of oil-board in place of the various metals also simplified production and reduced costs.

Seen in context, the Marsh Company catalogue exhibits the relentless drive among American makers to automate aspects of stencilling. This process began in 1868 when Eugene Tarbox of Nashville, Tennessee patented a rotating disk that carried a stencil alphabet with numbers and special characters such as those for dollars, cents and pounds. The characters could be cut manually from the disk with steel punches similar to those used in typefounding, thus coordinating several technical paradigms later reconfigured and elaborated in stencil machines. The stencil machines themselves were developed along a fertile crescent that stretched from St Louis, where the invention was patented by Bradley in the 1890s, to the industrial outskirts of Chicago where several manufacturers established themselves. In between was Belleville, home of Marsh which by the 1940s appears dominant in the field.

It is tempting to read into both catalogues the larger narrative each suggests. Marsh was clearly on an upward course, probably flush from a good war in which stencilling occupied a significant place: eleven departments of the US government – all among the armed forces – are listed as clients. With them is a much longer roster of the corporate great and good who would power America’s postwar economy.

Graphically, the Marsh Stencil catalogue is infused with optimism and Midwestern good-humour, dedicated workers and businessmen as true believers, all rendered in the bright colours of 1940s offset lithography.

The Signier-Schablonen, by contrast, labours under a cover of decorative Modernism and cod-Classicism, though the appearance of a distinctly militaristic Mercury on the cover is appropriate – as messenger of the gods and as the god of merchants and traders. Its product offerings are shown somewhat austerely, and on their own would soon play a relatively minor role within the broader trajectory of the stencilling industry.

It is unclear whether the Sächsische Metall-Schablonen-Fabrik survived the war: no evidence of its continued operation has yet been found. Marsh, on the other hand remains, very much a going concern, though one for whom stencilling is only part of a far larger range of products and services. Marking, as the industry might more accurately be called, is now dominated by other methods of imprinting data on surfaces and objects; or has dispensed with direct marking entirely in favour of encoded data labels joined to computerised freight logistics and customer-accessed tracking services.

But it is unlikely that the diverse, informal circumstances of marking will ever disappear. And as long as these remain, the future of stencilling, a venerable and persistently multi-purpose technology, seems assured.

Top: Marsh Stencil, catalogue for stencil cutting machines and supplies, Belleville, Illinois, ca. 1947.

Eric Kindel, lecturer in typography, Reading and London

First published in Eye no. 40 vol. 10 2001

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.