Spring 2019

Pay it forward

Rubén Fontana devised a system for teaching typography that is grounded in Argentina’s culture and politics

Designer Rubén Fontana (b.1942) is a figurehead of design and design education in Argentina. Fontana endured the effects of the coups and periods of military rule during the 1960s and 70s. ‘Dictatorship dealt a blow to everything on a social and cultural level,’ says Fontana. ‘We were at an impasse; we just worked to survive.’ (See ‘Buenos Aires project’, Eye 63.)

Last December Fontana, now retired from teaching, sat down in his studio in Buenos Aires, FontanaDiseño, to discuss his long tenure, from 1985 to 2017, at the Universidad de Buenos Aires (UBA), where education in typography is part of the graphic design programme. UBA is a public and state-funded university which provides education free of charge to students from Argentina, and more widely to students from across Latin America. Furthermore, an egalitarian admission system allows all applicants who meet the educational prerequisites to enrol – no interviews or portfolio reviews. A consequence of this is large classes: Fontana recalls teaching classes of more than 300 students from the start of the BA Graphic Design Career course. The classes later grew to as many as 600, taught by fourteen or so professors – it takes a lot of teachers to lead such a popular course. When education is free, the teachers’ fees are meagre, but many academics are themselves former UBA graduates who view their teaching duties as a way to pay back and pay forward: they are repaying the privilege of free education by contributing to the next generation. And there is no obligation to pass students whose work does not meet the standards and requirements of the course.

Fontana said: ‘The positive aspect of such huge classes is that students have to learn to survive among so many people. When they finish their studies, it equips them for the local market and abroad. Students here must also work during their studies, which gives them perspective and a work ethic. When students graduated and went out looking for work, they widened the market and the demand grew.’

Fontana’s book Pensamiento tipográfico / Typographic Thought (1996) tells the story of building the course from scratch.

His syllabus aimed to ‘be the source of inspiration in countries which, like Argentina, have little experience in the knowledge and teaching of the art of typography.’ His detailed account explained how each session should be run and why, covering subjects such as ‘Developing sensitivity to rhythm’, ‘Visual memory’ and ‘Typography and identity’, and later ‘Typographic thought as a methodology of design’ and ‘Experiencing typography’.

No time for ‘stars’

Most remarkably, the staff conclude each day with a crit that sees students placing their work in long rows on the workshop floor. This model allows professors little one-to-one time with students, but Fontana had little interest in the ‘stars’ of his classes. ‘I was only ever interested in the whole group moving forward. Even those who don’t stand out have something to learn and something to teach. The most important thing is teamwork. Everyone co-operating. We played, studied, investigated, made and spoke together.’

Since Typographic Thought was published, teaching at UBA has developed in many ways. In 2007 Fontana started a postgraduate typography course, which grew into a programme for a masters in typography six years later. And it has expanded thinking about typography – for example, asking students to consider the role of written language in unconventional ways. One exercise that Fontana describes asks students to design communication systems for one of Argentina’s many indigenous peoples such as the Mapuche, Wichí, Pilagá, Toba and Guaraní. (The country has fifteen living indigenous languages.)

Fontana says: ‘Colonisation flattened native cultures and the development of languages was interrupted. No one is studying them. We care about the previous 500 or 600 years; we care about the culture, the laws, the customs. A written form of that culture is a way to not lose it.’ Zalma Jalluf, his co-director at FontanaDiseño, continues: ‘It is not a matter of reviewing the past, or nostalgia. Currently there are tens of thousands of people who speak Quechua or Guaraní. And in Argentina there is intercultural, bilingual teaching in Spanish and native languages, so typography remains important.’

The magazine tipoGráfica is another example of Fontana’s dedication to students’ understanding of international typography and type design. As its editorial director, he commissioned designers, type designers and historians from Argentina and around the world, including Félix Beltrán from Cuba, Martin Solomon from the US and Robert Bringhurst from Canada. While tipoGráfica had an international, professional readership, its prime audience was students; the magazine supplemented their education. Since it closed in 2007, no type or graphics magazine has taken its place.

Rubén Fontana and the typography programmes he founded at the UBA are an example of how to instigate change and propagate the importance of typographic design outside English-language and European models. While there are parallels to be drawn between approaches to typographic teaching all over the world, Fontana and his colleagues built a syllabus that has remained rooted in Argentinian cultures.

Thanks to Zalma Jalluf, and to designer Daniela Pedro, who assisted with translation.

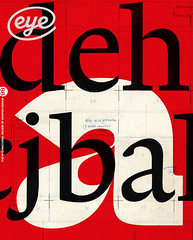

Top: Rubén Fontana’s tipoGráfica no. 1, July 1987, published in Buenos Aires.

Sarah Snaith, design writer, editor and tutor, RCA, London

First published in Eye no. 98 vol. 25, 2019

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 98 looks like at Eye Before You Buy on Vimeo.