Spring 2003

Reputations: Maira Kalman

‘I was out walking the dear dog and I saw 500 things that made me want to make art.’

Maira and Tibor Kalman met in college as English students and were together for 32 years, many of them as husband and wife, until Tibor’s death from cancer in 1999. While nurturing an ambition to write short stories, she helped Tibor found M&Co in 1979 (and was in fact the ‘M’ in the enigmatic studio name). For many years, however, while raising their two children, her contribution was usually behind the scenes. Then in 1987 she published her first book, Stay Up Late, illustrating David Byrne’s lyrics with an array of colourful primitive-looking characters and expressive type treatment designed by M&Co.

A year later she published Hey Willy, See the Pyramids, her first solo book. The sarcastic wit, absurd non-sequiturs and eclectic diversions, not to mention the naive drawing and painting style of this and later books, particularly appealed to the ageing baby-boomer’s ‘inner child’. Maira helped found a new genre of picture books that employed kinetic type composition as an expressive means of marrying word and image.

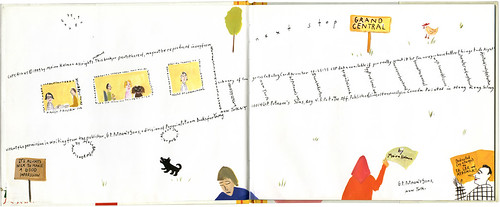

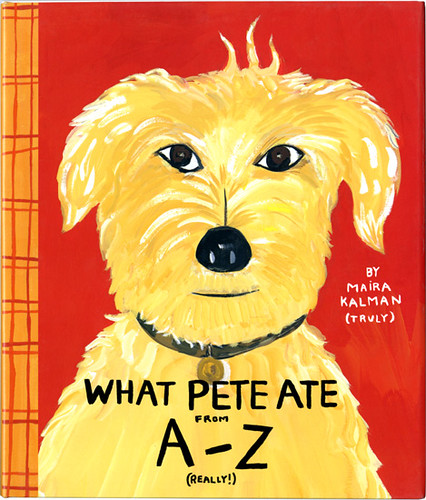

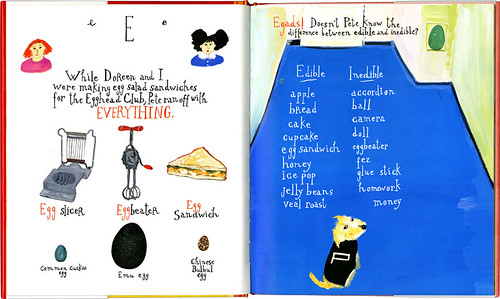

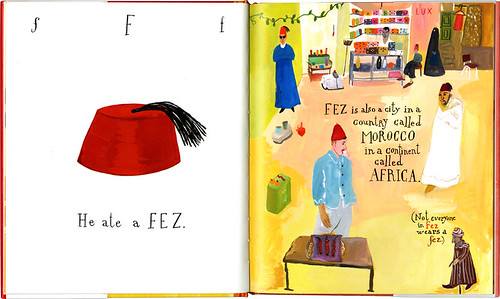

Maira’s major protagonist, a dog named Max, became an instant classic, winning children’s hearts and book awards. She also wrote and illustrated Chicken Soup, Boots; Next Stop Grand Central (based on murals she created for New York’s Grand Central Station) and What Pete Ate From A-Z (a culinary biography of her own mutt Pete). Each book revealed the Israeli-born Kalman’s own autobiography as they celebrated her love for New York City.

Spreads from Next Stop Grand Central by Maira Kalman, Putnam, 1999.

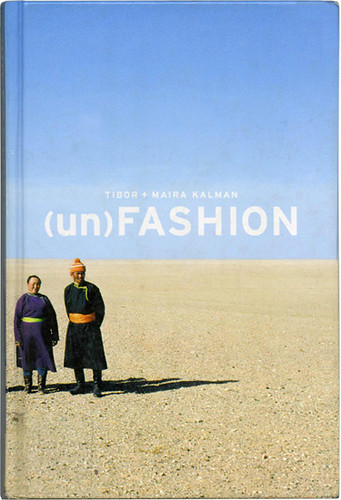

Before Tibor’s death Maira helped curate ‘Tiborocity’, a retrospective exhibition that opened shortly after Tibor died. Today she continues to work on projects that the couple had begun years ago, including (un)Fashion, a book about the way the non-Westernised world attires itself, and Colors, an anthology of Tibor’s work when editor of that magazine. She still runs M&Co, in its current incarnation as an entrepreneurial producer of paperweights, clocks and art ‘products’.

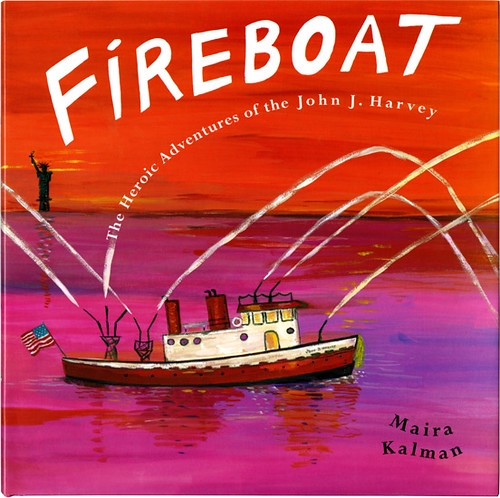

In addition to keeping Tibor Kalman’s flame alive, this one-time backstage manager has emerged as a significant artist and auteur in her own right. She has produced murals for Grand Central Station, windows displays for Sony, and clothes mannequins for Pucci. Her book, Fireboat: The Heroic Adventures of the John J. Harvey, about the decommissioned boat that fought fires at Ground Zero after 9/11, reveals a growing interest in fusing real life and art into an entertaining, though poignant form of social commentary.

Maira has reported for The New Yorker, produced commentaries on public radio, and is working with choreographer Mark Morris on a performance piece to be mounted at the mental institution Creedmore.

Cover (un)Fashion by Maira and Tibor Kalman, Abrams, 2000. Started before Tibor’s death as a counterpoint to our fashion-obsessed culture, the book takes a look at what the non-Western world wears.

Steven Heller: It’s more than three years since Tibor passed away. How are you doing?

Maira Kalman: I am doing as wonderfully and as awfully as can be expected.

SH: You just published a book of postcards of Tibor’s (and your) work called T.BOR linked to the retrospective exhibition ‘Tiborocity’. And you recently published the Colors anthology, as well as a book that you and Tibor had worked on together called (un)Fashion. It is often the role of the surviving partner to keep the flame burning – do you have any other memorial plans?

MK: Tibor as a legend, as a dynamic force, just won’t quit. I get testimonials daily (too daily, thank you very much) from people who have been profoundly influenced by him. Not to mention in the larger design sense, seeing the lack of him around. Not to mention in the even larger personal sense, not having him around. So the obvious answer is ‘No Way’. No more memorial plans. But, I do want to continue the (un)- series.

SH: During the heyday of M&Co you were, more or less, the silent but significant partner. What did you contribute to the firm and its legacy?

MK: Tibor and I met when we were eighteen and our dialogue was intense and honest from the beginning. We grew up through many culturally charged events and we also started a business and raised a family. But even though feminism burst into being one rainy night in 1969, we still had a conventional relationship in the sense that I was in the background. I was insecure about dealing forcefully with the outside world, but with Tibor I had someone who respected my ideas, humour, irreverence, zaniness. And I have to come back to the honesty. We bounced ideas back and forth in this creative atmosphere, but we could always be completely honest and we would not get hurt.

SH: What made you come further to the fore?

MK: What made me come to the fore was Tibor’s death. I thought you and a few friends might throw me on the funeral pyre. But then I discovered that I had accumulated a bit of courage. Maybe I had learned more than I knew from Tibor and maybe I realised that life is short, so why not do whatever you can think of that excites you. There is probably a myth about a woman not being able to really thrive without a man after a lifelong relationship. But people are incredibly resourceful. There are kids and friends and ideas and travelling to China. You know – life.

SH: You’ve inherited M&Co, so to speak. And while it’s not the frenetic, cutting-edge design firm it was when Tibor was alive, it still produces quirky products. How does it operate today?

MK: Tibor wanted me to not shrink away from the world. So he made me promise that I would continue M&Co. But I actually had my fingers crossed when I promised and he was too sick to notice. I would never in a million years presume to be a designer. I have insanely strong opinions about design. I know when I see the real goods, I think. But, I don’t want to design anything other than the odd thing that pops into my head. I am still coming up with products that The Museum of Modern Art [MoMA] distributes. That is fun, but not essential. I am finding that editorial work in all its forms is what excites me. I suppose I really don’t want any clients. Too complicated.

SH: What is your motivation for creating a new M&Co product? Entertainment? Enlightenment? Onion rings?

MK: So that my heirs and their heirs will bless me every year. I love that Preston Sturges invented the non-smear lipstick for the family company while writing his smattering of brilliant works. It is fun to imagine something, then to noodle around and then to see it happen. It’s the butterfly design paradigm.

SH: What’s the butterfly design paradigm?

MK: I made it up – a nice way to say dilettante.

SH: And what products have you produced?

MK: The ‘Prozac’ paperweight. I took our crumpled paperweight and listed all the antidepressants that people take. It was a long list. It was a reaction to the panic of a million discarded ideas. The room was littered with those. The other product is the ‘Zupa’ rubber ball clock. You were supposed to be able to bounce it across the room when the alarm rang. But it is more delicate than the ideal. So no wild bouncing. And I am working on a line of children’s toys / learning tools.

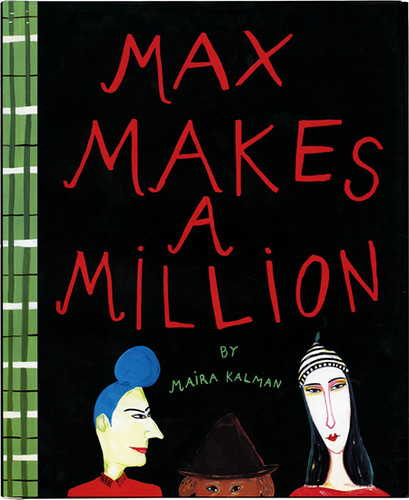

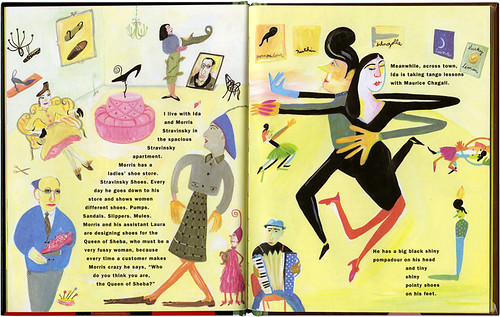

Cover and spread from Max Makes A Million, Viking / Penguin, 1990.

Top: Spread from Ooh-La-La (Max in Love), Viking / Penguin, 1991.

SH: You emerged in the 1990s as a popular children’s book author / illustrator with your Max series. Did you ever dream that your method, which was more primitive that the prevailing style of children’s books of the time, would take off?

MK: I doubt and question myself all the time, but I knew that I was giving people something very different in books and I knew that if I liked them, other people out there would too. The books are not cynical – which I also knew people would respond to. And they have tons of digressions that people understand, because that is what life is like. So I had no choice in what I was doing.

I followed my instincts. Not bad advice.

SH: Why did you decide to make children’s books?

MK: I knew I wanted to be a writer from the time I was a child. But I stopped writing in college because I thought my writing stank. So I did narrative illustrations, because I could tell my story. And since I did it from an unschooled place, it was a pleasure. I did that for about fifteen years. Then we had Lulu and Alex and I was itchy to do more than little illustrations. I realised that I could write and paint and that it was called a book.

SH: What was the impetus for Max? Was there some hidden agenda or mysterious past you wanted to explore?

MK: Incapable of making anything up, I look at my family, life, friends, and weirdos on the street. But where Max came from is a mystery. Sitting at my typewriter hitting keys, suddenly he appeared. And Max, of course, is kind of me. A nutty-kind-of-philosopher-comedian. Hardly veiled at all.

SH: What is the age range for the Max books? Are they for real kids – or for us addled kids at heart?

MK: No limit.

SH: How has Max done commercially outside of ‘our market’ of design-savvy hipsters?

MK: I think the Max books have a broader audience now. My early books may have had a somewhat urban and urbane readership. The books are still eccentric now, but not rarefied. Humour and optimism are universal connectors.

SH: Of all your work, what is the most exciting?

MK: The experimentation with language, painting and typography in the books. The making up of everything in the books, including architecture, fashion, industrial design, landscape – everything.

SH: And …

MK: What also is exciting is the dance project I am working on with Mark Morris for the AIGA. (He will teach us intrepid designers a movement piece and we will perform it at the once infamous Creedmore mental institution). The performer in me is always appearing. I think that in my ultimate fantasy world, there would be little difference between art and life. So I would like to be involved in performance pieces that are funny and emotional. Also there is a play that has been brewing in my decaffeinated brain for many years.

SH: And the renting of a storefront for a year with a bunch of people and – creating a museum of who knows what?

MK: I like curating, finding odd things that go together to tell a story. I also like selling things. It is nice to do things with other people part of the time. And when it gets boring I can go back into the studio or go for a walk by myself.

SH: There’s always something going on that does not pigeonhole you as an illustrator, designer, or whatever. So what is the play about?

MK: The play will be a cacophonous musical tanztheater (with a touch of Pina Bausch) that will tell the story of my family. Do I really know what it will be? No. Except I will have my mother in it.

SH: Sounds fascinating – can you tell me more?

MK: It’s totally fantasy. Except I know it will have Russian songs, and tangos, and other romantic evocative work. And Einstein may be mentioned. You can’t go wrong if you bring in Einstein.

SH: Your books were among the first to play with the conventions of children’s typography. Sure, Lissitzky and Schwitters had had this idea decades ago, but recently children’s book type had become rather stodgy. What made you and M&Co make kinetic type an integral part of your books?

MK: We had (I have) a big library full of our favourite work of Dadaists and Futurists and lots of other ‘ists’. And we both liked the surprise of vernacular design and hand-lettered typography. And I thought there was no reason for any part of a book to be boring. So all of these influences came together when the design was considered. The text was of a piece with the art. It was meant to heighten the communication. It makes sense. I don’t see why you would do it any other way.

M&Co was always preaching and practising social responsibility, but whereas Tibor addressed global issues, you are very local in your concerns. For example, as a teacher (at the School of Visual Arts MFA / Design Program) you have each student work with residents of the Greenwich Village nursing home as a way to tell their story through design or illustration. Do you feel that the majority of your work requires a socially responsible foundation? And if so, what constitutes this?

At the root of my work are two things (which can be subdivided into eight things and broken down into 22 subsets): a love of the absurd and a feeling of humanism for everyone on earth except Mrs Kelly on the eighth floor, who is a horror. But I can’t stand or can’t grasp politics. I can’t stand dogma. But I can really relate to the underdog.

SH: You were born in Israel and return there regularly. Has the situation in the Middle East made you more political?

MK: I am sighing as I say this: to me, it is becoming clearer that the existence and safety of Israel is critical for the entire world (not just for us Yids). But I am an optimist. The new generations of Israelis and Arabs watch the same TV and listen to the same music and wear the same jeans. That bodes well for rejecting fanaticism on both sides. So I am beginning to think of products that will rely on both sides for production. A notebook? A children’s book? Commerce and cross-pollination seem to be the key.

SH: Tibor believed that good design was a moral imperative. Do you likewise believe that design is a powerful tool?

MK: Design is stupendously important. Un-design is stupendously important. But there is nothing there if there is no content. That was Tibor’s point.

SH: What is the message you want to get out in (un)Fashion? Are you saying that jeans and MTV are part of the solution to the Middle East situation, or part of the globalisation process the culture jammers reject so righteously?

MK: I am saying that jeans and MTV could be part of the solution. Common ground. Common culture. But at the same time, unearthing the eccentricities, the style anthropology of tribes around the world is fascinating. So I guess both things are happening at the same time. I don’t feel qualified to talk about globalisation. Don’t like to make global generalisations. Each case is different. The peculiar twists and turns of the individual are much more interesting to me.

SH: What about the picture editing on this and forthcoming (un)- books. Was it instinct? Did you agonise for hours, or delegate to others, or both?

MK: Kevin Kwan was the photo researcher on (un)Fashion. He searched through zillions of pics. Lara Harris was the designer. Kevin and I edited. Lara and Kevin and I designed. There was instinct, agonising, delegating, re-editing, re-thinking – what there always is when you create a book.

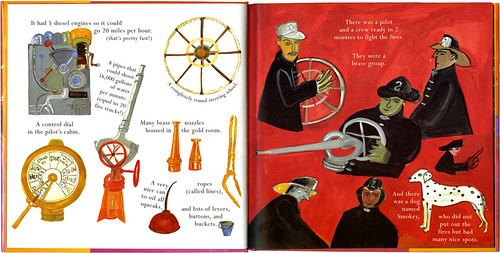

Cover and spread from Fireboat: The Heroic Adventures of the John J. Harvey, Putnam, 2002, an homage to the retired NYFD boat that helped fight fires after the World Trade Center attack on 11 September 2001.

SH: Over the past three years you have emerged as a quintessential New York artist. Your current book Fireboat about a retired NYFD boat that was used to fight the flames during the 9/11 tragedy is so much a tale of the city’s tenacity. You’ve created display windows for the Sony store, murals for Grand Central Station, and your New Yorker cover, ‘New Yorkistan’ (done in collaboration with Rick Meyerowitz). You are an outsider, so to speak, but you feel this passionate affinity with New York. How does it influence you?

MK: Being an outsider is a beautiful thing. Tel Aviv is my emotional base. My crazy family, who I continually depict, the beach, the heritage, etc. – all that comes from Israel. But coming to a new city, grey and blue and hard and noisy, and the Fifties and wow. Zam. This amazing energy. This new language. This sizzle. I got it right away. And I became a listener and looker. That is really my job. To report on the parade. There is no better, smarter, funnier parade than the New York parade.

‘New Yorkistan’ cover for The New Yorker, 5 December 2001, by Maira Kalman and Rick Meyerowitz. Art director: Françoise Mouly.

SH: What are some of your favourite New Yorkisms and how have you translated them into your art?

MK: Crazy artists and dreamers. Coffee shop slang. Yiddish. Fastness. Humour. Digressions. It’s all in Max Makes A Million and Chicken Soup, Boots – and the ‘New Yorkistan’ cover.

SH: Has the city changed for you over the years since you landed – or since 9/11?

MK: New York was, is and always will be, the epicentre of energy on Planet Earth. There is more humour and hope here per square foot than any place I have ever been. This place is the definition of life.

SH: So the answer is ‘No’. But what about people who have influenced you; you’ve mentioned Mark Morris as an inspiration. Who else do you admire and why, and do any of them influence you?

MK: Pina Bausch, Eleanor Roosevelt, Pippi Longstocking, Eva Hesse, Marcel Duchamp, Albert Einstein, Sara Berman [Maira Kalman’s mother]. I admire people who have a startling vision and strength of purpose. People who seem vulnerable, yet persevere.

SH: You have a Maira Kalman style to be sure. And I’ve seen others in recent months try to copy it. But what is most important for you as an artist: to have this identity, or something else?

MK: People have been copying it for more than a few months, Mr Heller! Arrogance aside, there is something deliriously inviting about whimsical illustration and writing. It seems like a breeze. But as always, you can copy the style, but that is all it is. So I am always unhappy with my last book and search for the newness in me for my next book. The style is consistent, but I hope that I am changing as an artist and experimenting. But having said that, the writing and ideas are really what count, because after all, you can say that I really can’t draw.

SH: What constitutes good drawing, and what would you call the kind of drawing that you do?

MK: I am flitting between art and illustration. Maybe it’s the ‘I didn’t learn this in school’ thing, which can be looked at as good and bad. Maybe because I am not serious – my style is naive narrative whimsical. I would like to be associated with Ludwig Bemelmans and Charlotte Salomon and Florine Stettheimer and Jim Nutt and other nuts.

SH: How do you make things – hands-on, or by hiring helpers? Is there a staff at your beck and call?

MK: I have a wonderful person named Meaghan Kombol who sits across from me and wonders what the hell she is doing there. One minute she is wearing a giant sandwich costume for a film. The next minute she is organising a party at The New York School of Dry Cleaning. She produces my books, pays the bills and generally does all that needs to be done. When it comes to the products, MoMA handles research and production.

SH: Coming up with startling, witty, un-programmed ideas seems paramount in your creative life. How do these ideas emerge? Can you give me a vivid description of your thought process?

MK: First I make myself a nice big cheeseburger. I have found that Cheddar is best for ideas. I may be lucky that I did not go to art or design school. I may be lucky that my mother never stopped me from daydreaming. I may be lucky I was born with a sense of humour. I may be lucky that I have a round nose (and growing by the minute). I don’t know. How ideas emerge is a mystery. And as you know, when you are looking for one and there is nothing there, you can go into a big fat panic. I just let my brain go. And I try to think of the things that I love and things that inspire me and somehow I travel to a real place.

SH: So, what are you thinking right now (aside from ‘what an idiotic question’)? Is there anything at this moment, or this day, that makes you want to go out and make art?

MK: I was out walking the dear dog (who is a sweet meal ticket – two books about him, one New Yorker cover and a back page) and I saw 500 things that made me want to make art. I ran into a father taking two kids to school. The girls were wearing green skirts and orange rain boots and one of them had a ponytail and was carrying a pink book and was pigeon-toed. Then I saw a man wearing a bowler hat with a feather and he was wearing an eye mask like Zorro made out of a twenty-dollar bill and I thought, ‘There is a God. Thank you, whoever is showing me this.’

SH: There are few things that you are unwilling to try. Just last year, as a reporter, you covered a convention of philosophers, and published a piece for The New Yorker ‘Talk of the Town’ on Alex Melamid and the Rubber Band Society. What are some of the other unexpected adventures you’re doing that we should expect?

MK: I am going to have a one-woman show at the Julie Saul Gallery where I will do things like hang out and fold fabric and have my mother iron clothes. I will also have paintings, so that we can all hopefully make some money. But I am interested in the events part. And that is about having fun – just plain old fun.

You are always thinking of weird ways to make a scene (in the best possible sense of the word).

SH: At your Colors book party last spring, your mother ironed handkerchiefs printed with Tibor’s quotations – I still have mine, nicely pressed and folded, and I can’t bring myself to blow my nose on it. You’d make a great party planner. Have you ever thought of doing some kind of performance art? Something using narrative?

MK: The play, the gallery show, the store front, the Mark Morris, walking to the post office. I think that is one of the places I am heading.

SH: Okay, if you had a chance to do anything this year without worrying about money, fixing dinner, or folding the laundry. What would it be? What is the zenith of your creative urge?

MK: I would be doing exactly and precisely what I am doing every day.

Cover and spreads from What Pete Ate From A-Z, Putnam, 2001, an eccentric alphabet book that celebrates the appetite of Kalman’s trusty pooch.

Steven Heller, design writer, New York

First published in Eye no. 47 vol. 12, 2003

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.