Winter 1993

Reputations: Matthew Carter

“Type design had been seen as a brave but arcane business that requires a lifetime’s dedication. I’m happy that notion has gone”

Matthew Carter was born in London, England in 1937, son of printing historian Harry Carter. At nineteen, he went to the Netherlands, where he trained at Enschedé as a punch-cutter. From 1963, he worked as a typographic consultant to Crosfield Electronics and in 1965 moved to Mergenthaler Linotype in New York. He stayed with Linotype for the next six years and continued to freelance with the company after his return to London in 1971. Bell Centennial was completed for Linotype in 1978. Galliard, designed by Mike Parker, was finished the same year. Carter was typographic consultant to Her Majesty’s Stationery Office from 1980 to 1984. In 1981, with Mike Parker and two other colleagues, he set up Bitstream Inc. – the first American independent digital typefoundry – in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Bitstream Charter (1987) was the first new design to be produced. In 1992, Carter started a new venture, Carter & Cone Type Inc., with Cherie Cone. To date, the company has produced four typefaces: Mantinia, Elephant, Sophia (commissioned for a project in Design Quarterly) and a new version of Galliard. Carter’s other typefaces include Snell Roundhand, Cascade Script, Olympian, Auriga, Shelley, Video and V&A Titling, as well as Greek, Hebrew, Devanagari and Korean types.

Erik Spiekermann: Do you think there is any benefit these days in knowing how to use metal type?

Matthew Carter: It’s nice that some design colleges still have metal type alongside the Macintosh, even if they have nothing in between. I think it’s difficult to understand how to measure type and arrange it unless you’ve had some experience of handling different sizes of type and how they combine more easily if you’ve put them in a composing stick. Obviously this can be learned in other ways, but I’m certainly pleased to have had the opportunity of handling type myself.

ES: My theory is that it’s only technology where you work with the stuff between the letters.

MC: Yes. You understand that there’s a fixed amount of space on either side of a letter a little bit at the top and bottom.

ES: And then if you are designing a page in hard metal, that page had to be filled, you can’t just plop the type on the printing press.

MC: I think that whether you are talking about the physical properties of a single piece of type and how it relates to its neighbours or about the architecture of the page, it’s easier to grasp if it’s something physical, something you can pick up and hold in your hand.

ES: One thing you learn with metal type is economy – there is a limited choice of sizes, so you can’t set in 17 point, it has to be 18 or 24 or 36 point.

MC: Anything that forces you into a close relationship with letterforms – in may case it was making type, but it could have been calligraphy or stone cutting – gives you a different perspective. It’s so easy to change one’s mind on the computer, and though that’s a great thing – for me, design is about changing your mind until you get it right – I think it’s useful if you’ve had in you past the experience of having to make up your mind once and then do it. If you’re cutting lettering in stone, you’ve got one shot, and if you blow it you’ve lost a day’s or a week’s work. So you have to think very hard before you commit yourself. Similarly if you know you’ve only got 14 point and 24 point in the case, you’ve got to work with those. Although I tremendously enjoy the luxury of the unlimited choices you get with the computerised medium we have today, I still think it helps if you’ve learned in a situation where you have fewer choices and only one chance to get it right.

ES: What do you think about the new technology that will enable us to have all the intelligence of handwriting? You’re obviously more familiar than I am with TrueType, the automatic substitution of characters and ligatures, digitised handwriting? Erik van Blokland has designed a face for comic books [Kosmic, see page 55] based on three different versions of handwriting with a programme that randomises characters so if you have a double “m”, for example, it automatically inserts two different versions. You’ll never be able to tell it has been typed.

MC: All that interests me very much. It’s one of the curiosities of our script that it needs only one version of each letter, or at least one set of caps and one set of lowercase. This is almost unique –it is certainly not true of the Indian languages or of Arabic. But because the technology of typefounding was developed in the Latin world, the technology we’ve lived with ever since has been designed for dealing with scripts with a single form for each letter. There were more ligatures in early fonts of type, and we also used to have two lowercase “s”s, long and short. Very little of that survived. It is very difficult for metal or mechanised type to deal with them multiple letterforms of Arabic and Indian scripts.

With today’s technology, however, it is possible to deal what typefounders used to call exotics. And out of software manufacturers’ efforts to mechanise Hebrew, Arabic and Devanagari with all their scribal refinements has come the possibility of going back and doing the same thing with our Latin script. It’s an opportunity to create ligatures we haven’t had before, or to do what you describe Erik as having done, that is to put multiple variants of every letter in there. Which variant you use can be determined either by logic – by which letter comes before or after, for example – or randomly.

I think it’s one of the few things that might make our type more interesting and considerably more legible. I have experimented with old-fashioned italics, which are closer to handwriting than roman. These italics have large numbers of ligatures, and the interesting thing is that they disappear as you read it, they blend in perfectly. They not only make it livelier, but also make it easier to read. It’s a miracle that a lot of things to do with the computer, and with the Macintosh in particular, are as right as they are, and I don’t complain about them very much. But the font we have come to accept is too small, so the idea that we can treat a typeface as a database with all the variants, different figures, ornamental characters, contextual forms and so on is exciting. I’ve been involved with Apple in looking at this.

ES: It’s as though type and writing are going to merge.

MC: I think we should remember that we’ve only have access to formal type for about 500 years. I teach a short type design course at Yale and when the Macintosh came along I noticed that one of the favourite student projects was to design handwriting-based typefaces. This was a thing that for technical and economic reasons was unthinkable in the past. You would have had to have been a millionaire dilettante to conceive of making a typeface that was personal or idiosyncratic, and of course if you knew anything about type you would have read people like Frederic Goudy saying how dangerous it was for amateurs to experiment. But today you can sit at the Macintosh and scan in anything, including handwritten sources, and then do what I suppose Erik has done, which is to select a number of letters and arrange them in your font. I think the arrival of pen-driven computers and this interest in the less formal forms of typography, vernacular typography or whatever you like to call it, is very interesting.

ES: For years we’ve been talking about the fact that screen-based multimedia needs its own typefaces, but doesn’t that mean that the screen will go on imitating paper?

MC: I’ve been talking recently to people involved in on-line information systems, where you subscribe to information and it comes up in magazine form on your screen. All their metaphors come from filing cabinets, envelopes, business cards, the office environment as it was before there were any computers – it’s very low-tech. We haven’t got to the point yet where we have ways of looking at documents and information that have only existed on computers without metaphors from paper days. It reminds me of something I heard Alan Kay say a long time ago, which is that we are conscious of using computers. We are still, today, at a stage where everyone is very self-conscious about using computers.

ES: Neville Brody believes that the way we treat the possibilities the computer offers in terms of interface and type design is terribly old-fashioned, that we’re going to be communicating on screen with all sorts of digital grunts, more pictograms, logo symbols, Assyrian or Phoenician bushels of corn and so on.

MC: I had a conversation a few weeks ago with the musician Peter Gabriel about the question of a universal sign language. I don’t mean highway code or danger signs, but a sort of visual Esperanto that the younger, “post-literate” generation can all understand, even though as far as speaking goes they know only their mother tongues. I guess he was concerned about making music videos and how to express things graphically that people would understand all over the world.

ES: We’ve just finished work on the latest FontShop catalogue and a lot of new designs are for logos, dingbats, symbols, pictograms – for example, a dingbat for a fax. Is this pointing to the death of the alphabet?

MC: There is a small vocabulary of absolutely universal symbols, but it’s not really enough to converse with or to make any abstract point. But I can imagine a sufficiently universal knowledge of certain symbols to enable you to communicate with people non-linguistically. When I’m in Japan surrounded by kanji I can convince myself that the alphabet was an aberration and that in a few centuries we will all be back to pictographic scripts. Much easier.

ES: It seems to me that there is a large market of non-typographic users who buy typefaces like they used to buy golf balls or daisy wheels, and then there is the other market of printers, publishers, and so on who buy the fashionable and sophisticated stuff.

MC: I think the computer has thrown the market open. Ten years ago no one would have questioned the fact that type was an autonomous industry, but today it’s part of the software business. I think the people who will have be having an increasingly hard time are the larger font companies, Adobe and Bitstream and Agfa and Monotype, because moving large libraries of type has got a lot more difficult thanks to cheap font packs and the number of fonts resident with hardware and software when you buy it. The big repertory of “type by dead guys” that everyone has to have is going to get harder and harder to make money out of because a lot of people have it and it’s not easy to protect it legally.

So I don’t think we can expect the sale of large amounts of existing type to continue to fund the development of new faces. New faces will have to fund themselves and they can only so do if we have a two-tier pricing system. I talked to Zuzana Licko about this and she says she wouldn’t mind selling fonts for a buck or two if she got a nickel every time one of them was used on television. That would be wonderful, if we had something like the situation of composers and musicians who get performing rights, but it is inconceivable to me that the type industry would have as much muscle.

We’ve been selling retail fonts for a year now. For a single face we charge about and we’ve never found anyone who said they’d buy it if it was rather than . I’ve just been reading about David Carson, who’s putting the Ray Gun fonts on sale for 0. He feels they can take it or leave it and I think he may be right. There has to be a price differential between the large existing libraries and the sort of haute couture that otherwise won’t survive.

ES: The people who want to use a typeface for professional reasons or to be the first on the block to do so would pay , or 0.

MC: We sell type to graphic designers, but we’re always surprised by who some of our other customers are. There are doctors and dentists who are discovering type because they have computers. They’re not always very sophisticated at first in how they use it, but they are getting quite interested. At one time they would have sent someone out to buy a golf ball, but now, because these humming beige boxes are so universal, they have to make typographic decisions, including buying a font of type. Sometimes they become good customers, buy anything we make.

ES: So the market is still expanding.

MC: Two or three years ago there was font-feeding frenzy and type was being bought in very large amounts. I think one of the problems the larger companies are facing is that that’s blown over, whether because of the general economic situation or because people got bored with having too many fonts. It seems to me that people aren’t so silly about fonts as they were.

ES: It used to take five or ten years before a font issued by someone like Adobe got into the mainstream, unless it was hyped like Lithos was by MTV using it. Is that still the case?

MC: Particularly in the case of text faces there is a long delay before a font is assimilated. When we put our version of ITC Galliard on the market a year ago with its expert sets I think we benefited greatly from the fact that the face had been around for 15 years and was already relatively well known. I’ve been very pleased by how quickly people have adopted Adobe’s Lithos and Tekton – the rate at which they have been appearing in print and on television is amazing. And then the Adobe Garamond has done astonishingly well too, so perhaps in today’s markets there’s less of a distinction between text and display faces.

ES: At one time Adobe used to issue a lot of free type specimens to promote their fonts, but now they seem to have stopped that. Today, no one knows about new faces.

MC: The tactic we have adopted is to print type specimens for new display faces. We produce brochures – the one for Mantinia is 12 pages, the one for Sophia just four. Graphic designers have been complaining for a long time about the lack of type specimens and I sympathise –it’s like buying software without a manual. That’s particularly so in the case of the two faces I mentioned, which have non-standard character sets so you need a manual to know where the ligatures and so on are on the keyboard. You and I grew up with access to wonderful Monotype specimens and probably learned our trade largely from typefounders’ specimen books.

ES: Obviously with a fairly large market and lots of fonts, the cost of printing and mailing a type catalogue becomes prohibitive.

MC: One of the subjects independent type designers – David Berlow and others – talk about more than anything else is the idea of pooling our marketing resources in combined mailings or even some sort of combined catalogue. There used to be very well-produced typographic journals such as Fleuron and Signature which had wonderful type specimens, sometimes tipped in, and these seemed effective ways of getting type in front of the people who want to know about it. I think we may see something like that again in the near future. There was a marvellous exhibition of type specimens at ITC in New York a few months ago. They showed the typefaces in a good deal of detail and also suggested ways in which they could be used, which is a very valid approach for today’s developing market.

ES: I know it’s almost a trade secret, but how long does it take you to design a text face in just one weight?

MC: It’s a hard thing to answer because I never start a new face on Monday morning and work on it without interruption until it’s finished. Sometime you have to produce something very quickly to meet deadlines, but in such cases it’s usually not very original or innovative. I was at Bitstream for about ten years, during which time I designed only one typeface. Towards the end I was quite frustrated that I couldn’t do more work on faces I had on the back burner, but now I’ve had an opportunity to go hack and work on them properly. I’m please I didn’t finish them earlier. I’m sure the work I’ve done on them more recently has improved them a great deal. So in some ways I’m not sorry when projects get spun out over a period of time because I’m convinced they get better, at least in my eyes.

ES: You still haven’t given me a figure.

MC: I find it extraordinarily hard to do so. I mean, you can sit down at the Macintosh and make a typeface in two days, but it’s probably not going to be very interesting. Then I like to work on more than one project at a time. Some of the commissions I’ve been doing recently are very large, multiple master faces with endless weights and widths and axes. It’s nice while you are working on one of these huge, complicated projects, which takes months, to alternate it with a one-off thing, a single face in a single weight. Bang, do it! I’m not trying to be evasive but it is difficult to say how long it takes.

ES: My experience is that it takes about 120 hours to do one weight of a new typeface that is started from scratch – about an hour per character. It took me 400 hours to do three weights of Meta, which is the first face I did in the early 1980s, though that was in pre-laser writer days. So if you look at a decent hourly rate, which for guys like us should be about 0 an hour, you should charge ,000 for one weight, which is out of the question. Maybe in ten years time your new version of Galliard or Mantinia will have generated enough revenue to allow you to buy the odd pound of coffee.

MC: My working like has two parts. First there is speculative font design, that is designing new faces for the retail market. You design them, you put them out, and you hope someone buys them. It’s going to take a long time for you to recoup your outlay on that, particularly if you print type specimens and try to do it properly. At the same time I also have commissions for new faces from computer companies and publishers and so on. I didn’t know this would happen when I started, but it’s lucky it has since it is cash on the nail and it’s sometime relatively well paid. Although we said earlier that selling large libraries of type will not pay for the development of new faces, I think doing commissions possibly might, particularly since we only sell a period of exclusivity, so once the clients have banged the face about for four or five years and got bored with it the right revert back to us. I’m glad of that because I suspect most type designers don’t have an infinite number of ideas.

ES: A lot of people – including, of course, our friend Massimo Vignelli – see all this new work as visual pollution.

MC: I totally disagree. I think that when you look at the face from Emigre Graphics or Ray Gun or any of these young designers, including students at CalArts and Cranbrook, it’s not very important whether you like this font or that font. What is exciting is that there is so much going on. For most of my life type design has been seen as a brave but arcane business that requires a lifetime’s dedication to produce a single typeface. I’m happy that notion has gone, that type design has been demystified. You can look at some of the stuff and suck your teeth and shake your head, but the fact is that I can’t think of any other period in the history of typography when I would rather have been at work. At the moment we have a tremendous pluralism – a lot of people are still buying very classical type designs and using them very well and others are buying very weird type designs and using them. I think that’s all wonderful.

ES: Some kids in my studio are turning out music fanzines and they make a font a day. Almost every author creates his or her own typeface for use on that particular page.

MC: We’re back to holographic typography, like William Blake and Edward Lear and so on.

ES: Everybody with ten fingers and a computer is a type designer.

MC: I’m often asked whether I think these new fonts coming out of California or Amsterdam or wherever will be assimilated in the same way as the type designs of the past. I try to answer by pointing out that when Baskerville first appeared in 1757, people thought it was so shocking in comparison with Caslon that they said it would make you blind. The strain of reading Baskerville after a lifetime of reading Caslon would do ophthalmological damage. It seems odd nowadays that Baskerville was regarded as an unacceptably revolutionary type – however much Vignelli and others may dislike Emigre, I’ve never heard anyone suggest that reading it is going to damage your eyes. So things are assimilated despite initial horrified reactions.

ES: Is there any such thing as bad type?

MC: I do think there is bad type, but not all bad is type is type that has been created overnight. There are as many bad typefaces that have taken years to produce and are part of the canon of typography as there are among student work. And more importantly, there are graphic designers who are capable of making any typeface look bad.

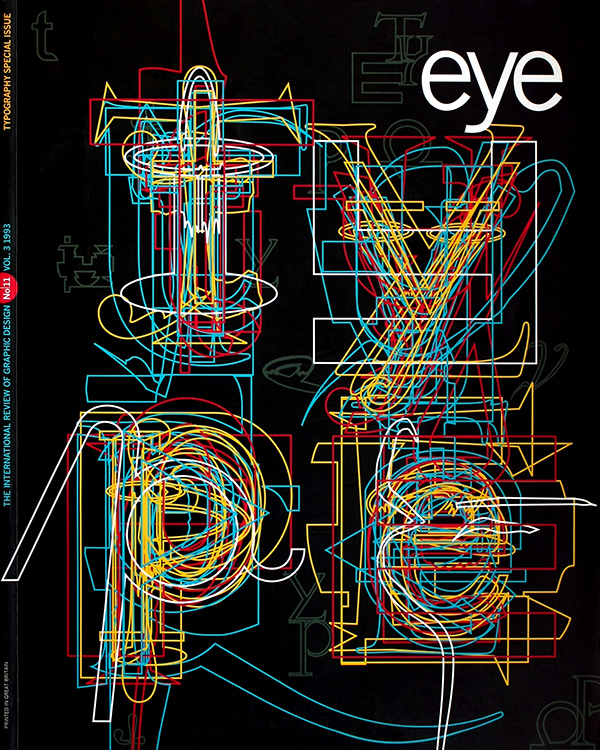

First published in Eye no. 11 vol. 3, 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.