Summer 1992

The digital wave

Charles Bigelow

Frank Blokland

Matthew Carter

Barry Deck

Adrian Frutiger

Erik Spiekermann

Erik van Blokland

Just van Rossum

Petr van Blokland

Bram de Does

Gerrit Noordzij

Martin Majoor

Jeffery Keedy

Veronica Elsner

Zuzana Licko

Carol Twombly

Robert Slimbach

Sumner Stone

Gerard Unger

Donald Knuth

Hermann Zapf

Jan van Krimpen

The old manufacturing companies that dominated typeface production have been swallowed and largely pushed to the sidelines. By Robin Kinross

The old manufacturing companies that dominated typeface production through most of this century have been swallowed and largely pushed to the sidelines, while initiatives in design – and in the terms and routines that condition design – have been made by a few rapidly growing software and computer hardware companies. Pathbreaking contributions have come from small studios or individual designers working, in every sense, from just a desktop. There have been ‘font wars’, corporate piracy and copyright contravention on a large scale. To use the loose terminology by which we attempt to carve up typographic history, it is clear that during the 1980s, the developed world left behind photographic typography (to which metal had ceded) and entered the era of the ‘digital’.

Digital processes were introduced into typesetting in the 1970s, but – as always in the development of human inventions – it has taken some time to realise their full implications. ‘Digital typesetting’ means that characters, and indeed any other graphic elements, exist only where they can be generated by the rectilinear sweep of a beam, either on or off. As against the apparently infinitely subtle possibilities of a hand-guided engraver cutting punches for metal type, or a pen or brush putting ink down on paper for photographic reproduction, there is an obvious bargain to be made with the technology. You have to settle for the squares the grid can allot you.

At first, in the early years, the deal seemed a bad one. Typefaces were designed within, and sometimes even in celebration of, the technical constraints of the moment. Instances of this approach were Gerard Unger’s Demos, Adrian Frutiger’s Breughel and Matthew Carter’s Video. Now these ungainly productions are gathering a period charm.

Seen from the desktop, one might think of the new era as the Macintosh age: opening in January 1984. This has been the reality for most designers, though it is a partial account. And now that the PC has all but caught up with the Macintosh, and the giant (IBM) signed a peace treaty with the giant-killer (Apple), it is a view that has lost its truth.

The ‘PostScript age’ might be more accurate. It was Adobe’s invention of a computer language able to describe text and images within and between processing units and printers which brought typesetting to the desktop. Typefaces were no longer tied to composing machines. Anyone in possession of font design and editing software could make their own typeface and have text set on a machine that might bear the name ‘Linotype’, but which would be hospitable to any instructions in the common language.

This transgression of commercial boundaries lies at the root of much of the turbulence of the recent period. The winners – in the law courts and the stock markets – have generally been the young companies who have managed to balance commercial self-interest with a generous sharing and spreading of knowledge to the vast numbers innocent of typography. It is an approach that has yielded the prospect of huge returns which could never have come from a mean, close-to-the-chest attitude.

The history of Adobe Systems may be the clearest case of the benefits of generosity. The founding partners, Chuck Geschke and John Warnock, left Xerox in the early 1980s to market the computer language (Interpress) they had helped to develop for that company. This language, then named PostScript, was licensed by Adobe to manufacturers of laser printers, notably Apple. At this point both Adobe and Apple found themselves getting into typography. PostScript laser printers were fitted out with 35 core fonts – a depressing selection that embodies the sensibilities of safe typographic taste of the mid-1980s.

At the early point, no one seems to have perceived the implications of the new technology for typography. But if a laser printer could output the shlock of Zapf Chancery, Bookman and Avant Garde, it could do the same for any other typeface, given the time and the right software. The other necessary component – programs for designing and making up pages – came along quickly. The concept of ‘desktop publishing’ was launched by Aldus Corporation (PageMaker) in league with Apple, and gradually it became possible to do serious typography with these tools: weekly magazines and 400-page books, as well as office memos and church newsletters.

The digital revolution has made possible new ways of designing and making type. The adoption of the terminology of metal typography – fonts, foundries and cutting – may be inaccurate and quaint, but it does suggest a truth. The designer of letterforms on a screen is making their final forms, without the mediation of a further copying or translation process. In this sense, the conditions of digital type design are like those of the hand punch-cutter, before the mechanisation of type design and production.

Two centres of research lie behind the development of software programs for the digitisation of letters. Donald Knuth’s Metafont project, based at Stanford University in the Silicon Valley heartland, was of immense theoretical and philosophical interest; witness the published debates about Metafont in the early 1980s. However, in its assumption that typeface characters could be modelled as simple strokes rather than outlines, Metafont backed the wrong horse. But in any case, as its name suggests, the aim of the project was to develop a program for conceiving typefaces rather than for drafting them.

The usable program for manufacturers has proved to be Ikarus, developed through the 1970s by a team led by Peter Karow at URW (Unternehmensberatung Rubow Weber) in Hamburg. In the familiar pattern for typographic development, designers were brought in to bring conscious formal awareness to processes in which decisions would otherwise have been made by default or imitation. Hermann Zapf made some contribution to the work at Stanford; Veronica Elsner joined the team at URW. In 1990, Ikarus was released by URW in an adaptation for the Macintosh. Before this, Fontographer (from Altsys) had become established as the usual designing and drafting program; now, with FontStudio (from Letraset) also on the market, the lay typeface designer is stuck for choice.

Adobe has seemed – to designers at least – to be the glamorous front runner among the new digital companies. Founded in 1983 in Mountain View, California, it has rapidly educated itself in typography to the point where it now begins to resemble the older typeface manufacturing companies in their heyday, in the role of cultural provider: the booklets that accompany Adobe’s new typefaces deserve a place on a bookshelf rather than in a filing cabinet, with their complete showings of the typeface, backed up by historical essays and bibliographies, as well as painstakingly designed specimens of the type in action. Adobe Originals have been primarily the work of the company’s two-in-house type designers, Carol Twombly and Robert Slimbach. They are of the first generation of digital type designers: Twombly is graduate from the course at Stanford run by Charles Bigelow, while Slimbach learnt type design on the job at Autologic.

While Adobe has been in the fast track, Bitstream, founded in 1981 in Cambridge Massachusetts, can claim to have been the first company freshly devoting itself to digital type. Two of the founding partners, Matthew Carter and Mike Parker, came originally from England and could draw on deep roots in European typography. The difference in the two company’s approaches can be seen in a comparison between Bitstream Charter, designed by Matthew Carter, and the Stone typeface family, designed by Sumner Stone at Adobe. Both typefaces were released in 1987; both are fresh designs, without particular historical models; both are fully digital in concept – if their designers started out drawing on paper, they soon got on to working on screen. Most importantly, both were designed to take account of the new conditions of digital output: the same forms have to exist on low-resolution laser printers and high-resolution image setters, and are generally tougher and blacker than typefaces used to be. Both also take notice of the fact that quite informal texts are now typeset: in the case of Stone, an ‘informal’ variant, for what one might call office typography, is offered.

But standing out against these common assumptions are different formal visions. Where Charter is hard, even a little awkward, Stone opts for the no-problem curve: compare the ‘a’ or ‘g’ of Charter and Stone Serif. I used to think that this smoothness in PostScript typefaces was an inevitable function of the Bézier curves that constitute their forms, but the comparison of Stone with Charter, made with the same technology, suggests that the reasons for creamy smoothness or critical sharpness lie deeper in the cultural backgrounds of the designers: West Coast or East Coast, America or Europe, drawing or cutting.

Bitstream and Adobe have grown to share centre stage. One index of their new establishment status is the fact that both Sumner Stone and Matthew Carter have now left to set up their own small ‘foundries’. Still hanging on in the centre are some older companies with roots in making typesetting machinery: Monotype, Linotype-Hell, Berthold, Agfa Compugraphic, Scangraphic. As the compound name suggest, they have been through troubled passages: forced marriages, adoptions and re-adoptions by transnational controlling corporations. While able to draw on their own rich typeface libraries, this historical baggage has tended to prevent fresh thinking about what might be appropriate in the new conditions. Now and then Monotype stirs itself to issue a booklet that, in usefulness and critical insight, outstrips anything from Adobe. But even in its trim new guise as Monotype Typography, the forces are against it.

Young middle-aged companies such as ITC and Letraset – the latter transnationalised some years ago – which played significant parts in post-metal but pre-digital typography, have been able to keep afloat, to find niches in the new landscape. Thus Letraset has moved into the software market, and ITC continues as a developer and marketer of typeface designs, without the burdens of manufacturing material product. But in the cases of these companies, too, there has been little evidence of new design approaches.

It is at the other, small-scale extreme of the typeface production field that much of the running has been made. Zuzana Licko’s typefaces for the California-based Emigre plotted the growth of one species of the digital child: from a pre-literate baby (typefaces freshly changed for every issue of the magazine) to the first pair of long pants (Journal Extended). The early productions were rationalised by reference to the requirements of low-memory computing and low-resolution screen display and printer output, and show considerable ingenuity in juggling with a heavily reduced formal repertoire, to make coherent sets of characters. Now that these constraints no longer obtain, Licko’s work seems to have lost its impetus and Emigre – the magazine and the foundry – has taken on work from other designers, notably Barry Deck and Jeffery Keedy.

In Europe, the most interesting work has been done by Dutch designers who have emerged during the digital years from colleges in The Hague, Arnhem and (less so) Amsterdam. While the work of the Americans comes out of the brief history of graphic design, that of the Dutch has its base in formal writing and in the long tradition of Europe type design. This is true even (or especially) of the Beowolf typefaces of Erik van Blokland and Just van Rossum, which constitute a critique of the tendency to facile smoothness in PostScript type, and a return of the repressed element of writing. Or take the typeface Proforma, completed this year by Petr van Blokland (elder brother of Erik). As its name suggests, it is designed for setting the complex texts of business forms, and is equipped with an exceptionally enlarged character set. The work on Proforma included the design of a font editing program (Pika) and has extended over years: only to end up in the commissioning firm of Purup Electronic closing its type department. As all its characters confirm, this most technical of exercises is rooted in the disciplines of handwriting. And although he is one of the most computer-literate of designers, Van Blokland is a champion of the old pencil-on-paper methods.

The central figure behind the Dutch typeface renaissance has been the designer and teacher at the Hague Academy, Gerrit Noordzij. In the dull and confused years of phototypography Noordzij seemed to be a voice in the wilderness, proclaiming the primacy of writing behind all letterforms. Some of his own typefaces will soon be available through the Enschedé Font Foundry, established by his son, Peter Matthias Noordzij. The foundry’s first release, this year, is a version of Bram de Does’s Trinité, an exercise in calligraphically delicate forms made by De Does’ Lexicon, digitised versions of Jan van Krimpen’s typefaces, and of the Rotterdam Metro signing alphabet. Another Hague graduate, Frank Blokland (no relation to Petr and Erik) is currently selecting a Dutch Type Library for production and marketing by URW in Hamburg.

A principal outlet for the young Dutch designers has been the FontShop chain, centred in Berlin. Founded in 1989, FontShop instantly became the designer’s favourite typeface supplier: send your shopping list down the fax, and an hour or so later a motorcyclist will hand you the goods. Alongside this bread-and-butter work of rapid supply of a large selection of typefaces, the company has made design initiatives. Grasping the opportunity that digitised information can offer, the magazine Fuse published typefaces – or notes towards typefaces – for users to interact with and develop themselves. Among the novelty items, the company’s own FontFont ‘label’ has put out some serious stuff. Unable to fund development work, it depends on work submitted by hungry young designers. Arnhem designer Martin Majoor’s Scala stands out as a text typeface without exact historical precedents, but rooted in tradition. In a development that will become increasingly common, as Europe extends east, Majoor is augmenting Scala with a Cyrillic variant. And Scala will soon be joined on the FontFont list by Quadraat, from another Arnhem designer, Fred Smeijers. This is a surprising and original variation on old themes, disproving once more the idea that the stream of new roman typefaces might have dried up.

If one had to nominate the face of the time – as Futura was, circa 1930 – this could be Meta, designed by Erik Spiekermann and released first by FontShop, of which he is a founder and chief partner. Meta is the latest manifestation of the typeface Spiekerman has always been designing: the Deutsche Bundespost letter and the ITC Officina were steps along the way. As a thoroughly articulated sans serif, it meets the hard requirements of information design: signing, forms and tabular setting. But Meta is more than just an information-letter: witness its rapid adoption in other contexts, to the extent that almost every new and re-designed magazine has used it.

Some patterns emerge from this volatile scene. On the most immediate level, one could speculate about the new sensibility that digital typefaces are introducing: after a solid diet of Times and Garamond, some of the new text faces have a sharper flavour.

One obvious material tendency is the dissolution of the typeface manufacturing companies, to be displaced by computing companies learning typography as they go. Now Apple and Microsoft, which have transformed typography by default, are beginning to become conscious of it. Apple has begun to draw on the expertise of individual out-of-house designers: Jonathan Hoefler’s one-man foundry in New York is at work on new fonts for them, while Stanford teacher Charles Bigelow was given the job of conceptualising the TrueType (outline) versions of Apple’s city-name bitmapped fonts for use in System 7 and Microsoft Windows 3.1.

This brings us back to the basic terms of the digital revolution. The ‘font wars’ of the late 1980s ended in a truce. There would be two standard formats for digital letterforms, co-existing peacefully: Adobe’s PostScript Type I and Apple’s TrueType. During the long coming of TrueType, Adobe was encouraged to extend the logic of PostScript to discover Multiple Masters (see ‘The typeface as chameleon’ by Andy Benedek, Eye 7). With this new tool, some typographers’ wish for infinite modifiability in type has come true; or it may just seem an unnecessary luxury. TrueType, too, offers infinitely flexible and intelligent typefaces, which in the case of self-inserting ligatures may be good, and in the case of self-deciding swash letters may be pretty daft. Or not daft at all, when one remembers that ‘non-Latin’ is the larger part of the world, and that ideographic and otherwise non-alphabetic typography – in which swashes are communication rather than decoration – has been the poor relation, marginalised in every development in typography since Gutenberg. It is here, outside Western typography, that the digital revolution will have its greatest effects.

Robin Kinross, typographer, type historian, London

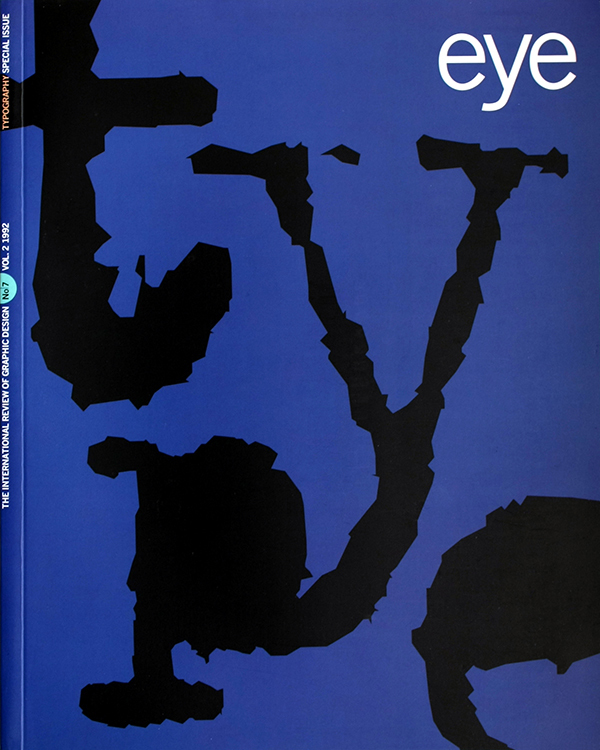

First published in Eye no. 7 vol. 2, 1992

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.