Winter 2003

The meanings of type

The back-stories, informed by trends, cults, philosophies and nationhood

Not every typeface is transparent, not all typography recedes; certain types symbolise philosophies and ideologies, some represent institutions, nations, and cults, many have intrinsic meaning. In about 1540 the French monarch François I commissioned Claude Garamond to design the typeface that bears his name. Believing that standardised typography would make governance easier, Garamond’s face was ordered to be used for all official papers, and became a symbol of French enlightenment as well as the nation’s first proprietary font. Around the same time Maximilian, the German king rejected Antiqua (used in Latin manuscripts) in favour of spiky blackletter.

In the sixteenth century, blackletter stood for German protestantism and nationalism, in the 1920s it was attacked for being antiquated, replaced by the New Typography, characterised by sans serif type in asymmetrical compositions and codified in 1928 by Jan Tschichold. In 1933, however, the Nazi government revived the blackletter face, proclaiming it Volk (or the people’s) type and condemned the New Typography as un-German.

Yet in 1941, the Nazis abandoned its own Volk type in favour of more readable faces. As if to prove further how mutable such symbolism can be, in the 1940s Tschichold lambasted the ‘New Typography’ as inherently Fascist, prompting a backlash by betrayed followers who saw him as Alvin Lustig characterised him, a turncoat.

Typefaces and typography are never designed in a vacuum. Practical and commercial motivations prevail but social and political rationales are never far away. Type design and typography are routinely informed by conscious and unconscious contexts that change with time. The following are some of the back-stories that underscore the meanings of type.

The slab serifs: big footprints

Late nineteenth-century slab serif wood types were a response to the job printers’ need for huge and durable display letters for bills and posters, and the original types were real work-horses. Despite their Victorian origins, there is nothing prim or proper about them. Slab serif faces exuded strength and masculinity – and are today associated with the printing of old wanted posters and vaudeville fliers. But throughout the twentieth century they were revived for various emblematic reasons. In the 1930s, for example, faces such as Girder, Karnak (R. H. Middleton, 1931), and Beton (Heinrich Jost, 1931), each derived from old Egyptians, symbolised the new industry manifested by American skyscrapers. In the early 1960s, however, an inexplicable interest in quaint Victorian pastiche returned the slab serif to curious prominence in the precincts of alternative publishing.

News Gothics – screamers on wood

The typographical term ‘wood’ is the jargon used by United States editors referring to so-called screaming headlines on tabloid newspaper front pages. The term dates back to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Large, sans serif wood types were common on advertising posters and broadsides because they grabbed attention without flourish or ambiguity.

In 1919 the New York Daily News, the first American tabloid newspaper started by Joseph Medill Patterson, used wood to announce with great fanfare the sensationalist – murder, sex, mayhem – story of the day. What distinguished the serious broadsheet from the scandalous tabloid was, in part, the difference between elegant Roman and gaudy gothic type. The conventions have not changed much, either. Tabloid wood may now be digital, but the goal is the same – to signal the big story.

Peignot – monument to France

In the 1920s the future of typography rested on German experiments such as Paul Renner’s Futura, the typographic emblem of modernity. In an attempt to outdo Renner, poster artist A. M. Cassandre and Deberny & Peignot proprietor, Charles Peignot, launched investigations that led to a sans serif face notable for its thick and thin body, and the use of upper case letters in its lower case form, which Cassandre christened Peignot – a testament to his boss. The face was actually the offspring of two parents: the Bauhaus and the Renaissance. After many false starts, Cassandre and Peignot decided to follow traditional lines, while at the same time avoiding copies of what had been done. ‘Copying the past does not create a tradition,’ wrote Peignot. Cassandre had the idea of returning to the origins of letterforms. ‘Was there not something to be learnt from the semi-unicals of the Middle Ages?’ queried Cassandre. ‘The idea of mixing the letterforms of capitals and lowercase seemed to us to contain the seed of new developments within traditional lines.’ The result was a quirky mixture of letters, which required a period of adjustment for the public to get used to. In 1937 the typeface was launched as the ‘official’ typeface of the World Exhibition in Paris, selected by Paul Valery as inscriptions for the two towers of the Palace de Chaillot.

A fabricator produced cardboard cut-outs for making complete alphabets, and these were also used for murals and exhibition stands.

Art Nouveau and psychedelia – youth and kitsch

Art Nouveau exerted an influence on typography throughout Europe from the early-1890s to before World War i. Designers Georges Auriol, Eugene Grasset, Peter Behrens, and Otto Eckmann, among others, filled foundry specimen books with curvilinear alphabets with eccentric calligraphic conceits. The style did not represent a political revolution but Art Nouveau (France), Jugendstil (Germany), Stile Liberty (Italy), and Vienna Secession (Austria) were youth-inspired social upheavals that altered visual language and spawned new moral and aesthetic values. Former visual taboos – including a prodigious amount of nudity – nudged out staid images. Sinuous Art Nouveau typefaces and ornaments were similarly erotic.

Yet not long after Art Nouveau was introduced it found mainstream acceptance, particularly in architecture, furniture, fashion, and graphics.

In France and Belgium Art Nouveau was the de facto national style. And even today kitsch French signs and posters include Art Nouveau alphabets. In the early 1960s, studios such as Push Pin in New York reprised Art Nouveau lettering; later in the decade, psychedelic poster artists in San Francisco adopted it as the code for the sex, drugs, and rock’n’roll generation. Art Nouveau’s youth culture underpinnings were, nonetheless, not the sole motivation. Victor Moscoso, the prelate of psychedelic posters, enjoyed the formal intricacies of the letterforms and became obsessed with drawing the ornate negative spaces between letters. The lettering for his original posters was hand drawn, designed to vibrate and shimmy.

Neuland and Chop Suey: faux ethnic

Neuland, designed in 1923 by Rudolf Koch, is a family of convex-shaped capitals reminiscent of German Expressionist wood-cut lettering. Reportedly, Koch did not make any preliminary drawings, which accounts for an informal quality that, according to a type specimen brochure distributed by Superior Typography, Inc. (c.1923), ‘expresses an atmosphere of exotic “flavor’’’. In addition it states there is an ‘unusual expressiveness; a subtle harmony of . . . ruggedness and delicacy of design.’ Neuland was recommended for advertisements promoting airplanes, boats, books, coffee, gifts, lacquers, rugs, tea, and tours, and was widely used until the 1930s when it was sidelined like so many novelty typefaces. But in 1993 Neuland was revived as the logo for Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park. Like an ageing actor, the old typeface was offered new roles as a curiously faux ethnic representation of Africa and third world cultures used on dozens of books. Similarly, the bamboo-looking novelty typeface Chop Suey (a.k.a Far East Type) has been stereotypically wed to anything Chinese.

Sans serif vs Fraktur: the Jewish question

Type design was scrutinised under an ideological microscope during the Nazi reign. Even before the infamous 1937 ‘Degenerate Art’ exhibition that ridiculed Modern art as decadent and ‘un-German,’ party ideologues dictated those typefaces that were verbotten, but many decisions were arbitrary.

A 1932 election poster featuring a stark, silhouetted portrait against black background with the name hitler in sans serif capital letters was decidedly Modern yet modern typography was later branded ‘Kulturbolschevismus’. During the Weimar Republic, blackletter was considered antiquated and ugly. Consequently, in addition to modern faces, like Paul Renner’s Futura, the humanist (and more readable) Antiqua had widespread use. When the Nazis came to power in 1933 Fraktur became the government’s semi-official typeface (and a symbol of its anti-Semitism as portrayed in Der Sturmer). Antiqua was Judenlettern (Jewish type) and at least one type designer – Lucian Bernhard who was not, in fact, Jewish – was vilified for his designs. Exceptions abounded. Some bastardised sans serifs (‘Jack Boot Gothics’) were sanctioned for use in party organs like the SS magazine, Schwarze Corps. Then in a turnaround the Nazis banned the use of blackletter typefaces in 1941, citing Jewish origins. The decision to deny Fraktur’s legitimacy was actually practical: German Volk typefaces were unreadable in the occupied countries.

Futurist / Fascist type: branding a movement

During the late 1920s the wood typeface Il Futurismo Artistico produced by the Italian type foundry S. A. Xilografia Internazionale became the trademark of the Fascist movement. In hand-set and hand-drawn iterations, in various weights and sizes, this moderne sans serif face was the model and semi-official typeface for party posters, signs, and periodicals. Slogans by Il Duce were also stencilled on walls using different variants. The original designer is unknown, yet iterations created by Fortunato Depero influenced a slew of Italian graphic artists at the time. As a member of the ‘second wave’ of Futurism, Depero typographically picked up where charter member Futurists left off with their invention of the cacophonous parole in liberta, which revolutionised typographic expression, yet relied more on old fashioned type styles. Depero injected an exuberance bathed in a Mediterranean palate that introduced a playfully dynamic Futurist aesthetic into commercial and political advertising. He adamantly rejected classical types in favour of eccentric streamlined lettering that symbolised speed.

Splash panel letters: typography parlant

Hand-drawn titles of comic strips, comic books, and even some advertisements comprise a genre (dating from the early twentieth century) known as splash panel lettering – so named for theatrical, or splashy, fanfare. Splash panel lettering telegraphs content and sometimes meaning, and although each is usually customised, they stem from the same root: exaggeration. The shadowed letters forming the word ‘war,’ in the comic of the same name, doesn’t actually symbolise either the terror or heroism of warfare but it does attack the eye with an explosive charge. The title Maus announces Art Spiegleman’s Holocaust memoir with a conventional comics trope that suggests shock, mystery and tragedy. And the word ‘horror’ in the magazine’s masthead is typical of the ersatz gothic lettering seen on old monster movie posters. Similar to architecture parlant, where a building’s structure expresses its function, this ‘typography parlant’ issues a narrative cue that tickles perception, sparks expectation and shouts a message.

Helvetica and friends: neutrality in person

If there are other typefaces that have triggered the same paroxysms of joy and fits of rage among designers as Helvetica, bring them on. Designed in 1957 by Max Meidinger, the face represents a Platonic ideal and a generic sterility. ‘Conceived in the Swiss typographic idiom, the new Helvetica offers an excitingly different tool,’ reads the promotional text in a D. Stempel A. G. Typefoundry specimen sheet (ca. 1958). ‘Here is not simply another sans serif type but a carefully and judiciously considered refinement of the grotesk letter form.’ Helvetica embodied the Modern mission to democratise visual communication, and was more effective in its neutrality than Futura (the fabled ‘type of tomorrow’). Following its introduction, first in Europe and then in the United States, Helvetica emerged as the readable, versatile, and modest typeface of choice for business throughout the multinational world. When the Soviet Union ministry of commerce needed to put a Western gloss on its ‘for export only’ publications and advertisements, Helvetica was used. When the New York City Department of Sanitation wanted to clean up its image, it specified Helvetica. When the Urban League, America’s foremost inner city Civil Rights advocacy group, wanted to appeal to white, middle-class donors, Helvetica came to the fore. Yet despite its democratic air, Helvetica has long been used to obfuscate corrupt corporate messages: such is neutrality’s double-edged sword.

Univers, designed by Adrian Frutiger and introduced in 1957, also sought neutrality in a chaotic typographic world. Though it certainly became a standard and ubiquitous typeface, it never had the same stigma as Helvetica.

Some say that Meta, created first in 1984 as the typeface for the German Post Office by Erik Spiekermann, and fine-tuned in 1995 for general application, is the Helvetica of the 1990s, and its widespread use underscores the point. Designed to be ‘neutral – not fashionable nor nostalgic,’ says the Meta website, it has yet to bear the same symbolic weight as Helvetica.

Avant Garde: behind the vanguard

Herb Lubalin’s art direction and design for Avant Garde magazine was regarded as ground-breaking in 1968. The magazine’s sophisticated marriage of alternative art and photography was framed by all manner of stylish typography, from Lubalin’s smashed-letter headlines inside to the intricately ligatured logo on the cover. The logo was so popular that Lubalin (and his partner Tom Carnase) created an entire alphabet of capitals. These were originally used for the magazine’s column heads, then commercially released by it in 1970 (with additional upper and lower case letters). Avant Garde quickly became known as the 1970s’ most emblematic typeface, with its array of quirky ligatures, used repeatedly on advertisements, magazine spreads, and posters. Maybe the name also seduced users; using it they could be avant garde, too. But it quickly became one of the most abused typefaces. ‘The only place Avant Garde looks good is in the words Avant Garde,’ type designer Ed Benguiat once complained. ‘Everybody ruins it. They lean the letters the wrong way.’ Even Lubalin lamented that he should not have designed so many absurd ligatures.

Template Gothic: off the wall

How could a typeface whose design was influenced by a handmade sign in a laundromat epitomise digital-era typography? Timing might explain why Barry Deck’s Template Gothic (1990) became the most well known and commonly used font during the 1990s. At the time graphic design was going through a technological upheaval; Modernism was challenged by an increasing number of heretics; universality had become the hobgoblin of cultural diversity. Template Gothic ventured into areas of type design deemed taboo. ‘The design of these fonts came out of my desire to move beyond the traditional concerns of type designers,’ Deck explained in Eye no. 6 vol. 2, ‘such as elegance and legibility, and to produce typographical forms which bring to language additional levels of meaning.’ After twenty years of grid-locked design, reappraisal was inevitable. Rudy VanderLans and Zuzana Licko of Emigre opened the laboratory doors and academic hothouses encouraged students to subvert. Conventional typeface design reprised or adapted historical models while strictly adhering to the tenets of balance and proportion. Template Gothic was literally ripped off the wall. ‘The sign was done with lettering templates and it was exquisite,’ Deck said. Although the original stencil was professionally manufactured and commonly sold in stationery stores, the untutored rendering of the sign exemplified a colloquial graphic idiom that designers previously had viewed as a gutter language. So, perhaps the best reason for Template Gothic’s success was that it did not invoke nostalgia, like itc Benguiat (1977), the emblematic type of the 1970s that drew inspiration from Art Nouveau, but evoked the present.

It also captured the conscious and unconscious needs of young designers to reject the recent past. Conceptually playful, experimentally serious, and purposefully imperfect, Template Gothic was a discourse on the standards and values of typographic form.

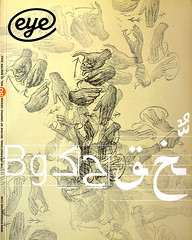

First published in Eye no. 50 vol. 13 2003

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.