Winter 2006

The world made visible

Motif, edited by Ruari McLean, was a quirky mix of art and illustration, with its roots in graphic art and typography

Motif magazine’s range of editorial interests was unusually broad for its time and, in the often highly segmented world of periodical publishing, it has rarely been equalled in Britain. An editorial in the first issue, signed by its editor, the late Ruari McLean, and its publisher, James Shand, quotes the nineteenth-century French writer and poet Théophile Gautier: ‘I am a man for whom the visible world exists.’ Motif, they go on to explain, ‘is a periodical for which the visible world exists’.

Over the course of thirteen issues, published from 1958 to 1967, Motif ran meticulously researched and beautifully illustrated articles about painting, sculpture, art education, graphic design, typography and lettering, illustration, photography, architecture, wood-engraving, and the history of the graphic arts. ‘Visual culture’ had yet to become a category of academic study and Motif’s urbane editor and publisher, whose careers began before the Second World War, would not have used the term. The magazine’s presentation of a wide array of visual arts on a more or less equal footing can nevertheless be seen as a prescient early example of a new way of documenting and appreciating the ‘visible world’.

The first editorial acknowledges a bias towards the graphic arts, yet McLean and Shand imagine the broadest possible readership for their journal. ‘Strenuous efforts will be made to make Motif appeal to the mind and eye of the non-specialist, the ordinary man who just wants to do exactly as he likes – but who is prepared to use his eyes to find out and evaluate what he likes.’ They emphasise the point in the second issue: ‘Motif is for the receptive whole man (whether, by profession, artist or laundryman) who can get visual pleasure from Pollock’s abstractions, Mies van der Rohe’s skyscrapers, Paolozzi’s sculptures, or Stewart’s sun, moon and stars.’ (Graphic artist Robert Stewart designed the cover and endpapers, and his work is also featured in the issue.)

Motif’s content, they write, would continue to be ‘unrepentantly and deliberately various’. For Shand, co-owner of the Shenval Press, this was the fourth ambitious visual arts magazine he had started. In collaboration with the editor Robert Harling, Shand (1905-67) had published the influential journals Typography (1936-39), Alphabet and Image (1946-48) and Image (1949-52). By all accounts he was a complex man – ‘strange and difficult’, observes McLean in his autobiography, True to Type. Shand was a bohemian in a business suit, much happier in the company of artists and writers, whom he met after hours at the Gargoyle club in Soho, than he was running the family business. McLean later remembered his colleague as ‘a man of distinguished creativity both as a writer, talker, and designer, who had been forced to stifle these gifts in building up a commercially successful and famous printing business, the Shenval Press.

A magazine gave him an outlet, besides beinga showpiece for his firm’s printing skills.’ McLean (1917-2006) had contributed an article about the history of the Egyptian letterform to the first issue of Alphabet and Image, and he recalled that it was Harling who mentioned him to Shand as a possible editor for Motif. Shand proposed to pay the salaries of both McLean and his assistant, Fianach Lawry (then Jardine), and gave them a room in Shenval’s Georgian offices at 58 Frith Street in Soho. ‘Ruari was very much an all-up-front person, certainly highly intelligent and literate, but I don’t think there were any mysteries, whereas Shand was a much more complicated person,’ says James Mosley, who contributed to Motif from the first issue.

McLean was already a published author and he loved magazines. ‘I was brought up to believe that reading magazines was a sin, or at least a waste of time,’ he writes in his book Magazine Design, published in 1969. ‘I could construct a perfectly good autobiography merely by writing down the names of the magazines I eagerly devoured at all the various stages of my life. My education (and certainly my general knowledge) probably owes more to magazines than to books.’

The first edition of Motif, published in November 1958, established the template for the following eight issues. Unusually for a magazine it had a hard cover, like a book; the binding was filled, front and back, with a hazily idyllic domestic scene, showing women at a table, drawn direct to silkscreen by Charles Mozley, who had also come up with the magazine’s name one evening. In subsequent issues, the endpapers were used for graphic art. The contents included the first instalment of a three-part history of photography by Helmut Gernsheim; a piece titled ‘The Born Illustrator’ by Edward Ardizzone; a portfolio of drawings and sculptures by Elisabeth Frink, with an introduction by poet and novelist Laurie Lee; a wry guide to art students by Richard Guyatt, professor of graphic design at the Royal College of Art; and an article about the type foundry of Vincent Figgins, 1792-1836, by James Mosley, recently promoted to librarian of the St Bride Printing Library.

Mosley recalls that he met McLean and other figures on the typography scene at the library, which they used as a kind of club, dropping by to see who was around. McLean asked him what he was researching and writing about, Mosley told him, and McLean commissioned him to provide it for the first issue: ‘It was as simple as that.’

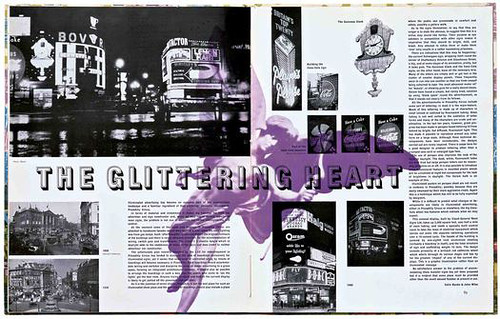

Below: No. 4, article about illuminated advertising in Piccadilly Circus by Colin Banks and John Miles: ‘No satisfactory answer to the problem of accommodating these monster signs has yet been proposed but it is evident that some place must be provided other than the much abused facades at present in use.’

Top: Motif no. 4, March 1960. Front and back cover’

This distinctive publication made an immediate impression. ‘The first issue of Motif is a tribute to the British graphic arts industry and equals anything that can be produced abroad. The contents are agreeable, readable and have civilised charm,’ wrote James Moran in Printing News. It drew attention in the general press, too. ‘As a vehicle for ideas, it may well become extremely valuable,’ wrote Quentin Bell in The Listener. 7

Shenval printed 2000 copies at the beginning, rising to 2500, except for one issue where, to McLean’s irritation, Shand arbitrarily cut the print run below the level needed to fulfil existing orders. McLean realised early on that Shand had no interest in developing a proper sales organisation, and this was a source of regret. Also, the magazine did not feature advertising at any point in its life. Shand never intended it to make a profit. ‘James Shand had to fight his brothers and board down at Hertford and Harlow to print and publish Motif because it wasn’t commercial enough for them, and they did not share James’s interest in and admiration for artistic things,’ recalls Fianach Lawry. In London, Motif was available from Better Books and Zwemmers in Charing Cross Road, Alec Tiranti in Charlotte Street, and other shops. In New York, it could be found at Museum Books and Wittenborn Book Co and it was stocked by bookshops in Chicago, Los Angeles, Copenhagen and Stockholm. It was also available on subscription to overseas readers.

Motif rapidly established a circle of enthusiastic contributors. A sense of how McLean and Shand operated can be gained from the entertainment expenses for 1960 to 1962 held in the Motif archive at the University of Reading. ‘Lots of people had these amazing lunches in those days,’ says Mosley, who describes McLean as a bon viveur who enjoyed the good life. Mosley was the magazine’s guest on four occasions in less than a year. Other names that appear in the expenses include Berthold Wolpe, Paul Rand, David Gentleman and Richard Hamilton, and regular contributors such as type historian Nicolete Gray; architectural critic Reyner Banham; Maurice de Sausmarez, head of fine art at Hornsey School of Art; and London gallery owner Robert Melville.

It was an eclectic mix of artists, art teachers, critics and scholars, whose interests might have been expected to appeal to quite different kinds of reader (it also seems doubtful that laundrymen were ever a significant part of the readership). Mosley suggests that the art subjects were ‘slightly weird in a journal which was on the face of it typographic’. He didn’t read these pieces and believes that Motif’s typographic subject matter was the central issue for McLean. The emphasis on art, Mosley suggests, must have come from Shand. In True to Type, McLean writes that Shand cared more than anything about the link that Motif’s content provided with art and artists, but says that Shand gave him a ‘free hand as editor. He never told me what to put in the magazine and never rejected anything I had chosen.’

McLean’s son, David, supports this view, pointing to a picture from 1961 in True to Type that shows McLean and Shand, caught in mid-gesture, at work in the Motif office. ‘My father was certainly a fairly powerful character,’ he says. ‘He looks happy in that photograph and he wouldn’t have been happy if James Shand was calling all the shots. I think he’s happy because James Shand was giving him a lot of rope and realised that he wouldn’t tolerate too much pushing around. I’m sure he wanted to contribute and he did contribute, but he left my father in overall control and must have, on the whole, respected his judgement.’ McLean adds that his father had wide interests and good contacts in all the creative fields: architecture, painting, graphic art, design and printing. ‘He mixed with all those people,’ says McLean. ‘He was very sociable.’

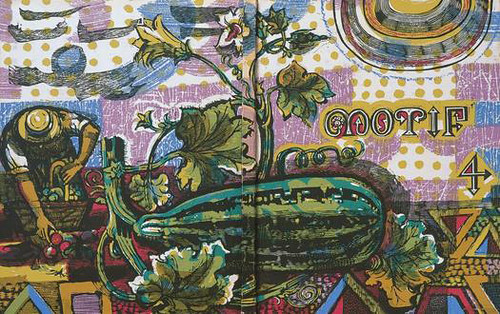

Where Motif truly excelled was as a superbly printed showcase for illustration, and this is one of the best reasons to search out copies today. Wraparound cover images such as Laurence Scarfe’s for issue no. 4, showing a gardener toiling under the sun in his marrow patch, are masterly feats of graphic art. Scarfe combines the old technique of linocutting with the new technique of silkscreen to build up intricate layers of colour and graphic texture. The magazine’s large pages abound with expressive ink drawings, experimental wood-engravings and radiant colour prints. In no. 3, a series of decorative drawings of shop fronts by John Griffiths possess a vibrancy of hue and a passion for eccentric descriptive detail, recorded with effortless delicacy and charm, that is rarely seen in illustration today.

In 1960, on a trip to the United States to attend the annual design conference in Aspen and promote Motif, McLean visited Milton Glaser, whose work he knew from the Push Pin Graphic. McLean suggested that Glaser contribute some drawings and Glaser, who had been looking at Picasso’s animal pictures, proposed a bestiary. The presentation of the twelve images in Motif no. 7 forms the most elaborate printed item to appear in the magazine. The folding pages open to reveal a display six pages wide that includes drawings of a lion, a grasshopper, a cassowary, a frog that appears almost to be clad in camouflage, and a mischievous red-faced mandrill. ‘It was most informal, as things in those days tended to be before marketing people controlled everything,’ recalls Glaser. ‘I did the drawings, he liked them and published them, and that was the end of it.’ It wasn’t quite the end of it: some of them were published in 1965 as a children’s book, with poems written in response to the images by Conrad Aiken.

Motif’s page design was as unrepentantly various as its contents. While images were always shown with a high degree of clarity and impact, McLean’s typography has none of the bracingly modern simplicity and consistency seen in Herbert Spencer’s Typographica, which was published at the same time. McLean designed each article individually, filling the two-column grid with a smorgasbord of type styles. In issue

no. 4, for instance, he uses Ehrhardt, Grotesque, Caslon, Baskerville, Bembo, Plantin and Juliana for text, and Times New Roman, Caslon, Gill Sans, Garamond Italic, Chisel, Echo and Sans Serif Shaded for headings. Mosley describes the lack of unity as a ‘shambles’. ‘I didn’t like it much really,’ he says. ‘I don’t think Ruari’s design was his strong point. He was better as an editor.’ In 1996, during a series of interviews about Typographica, I asked Spencer what he thought of Motif. ‘There is some very good material,’ he replied. ‘But it’s not presented in a very stimulating way, is it?’

The flexibility did have some advantages. Mosley’s article ‘English Vernacular: A Study in Traditional Letter Forms’ in no. 11 (Winter 1963-64) – the fruit of two years of obsessive research – runs to around 14,000 words and 106 illustrations over 53 pages. The only way to accommodate all this and to have the images move in parallel with the text was to use a three-column grid. There is evidence in the Motif archive that Mosley himself specified the text setting: 9pt Scotch Roman, 1pt leaded, on a 15 em column. The type’s appearance here is denser than usual, but for the most part, despite the lack of visual unity, Motif’s pages were highly inviting and readable.

For the tenth issue, Motif shed its stylish cover boards, which had always been prone to damage in the post and to warping. Pop Art covers by Peter Blake and Eduardo Paolozzi suggested that the magazine was making a not entirely convincing attempt to embrace the art scene’s new mood. From this point, the print specification was less elaborate than it had been in the magazine’s early 1960s heyday. Motif’s use of special papers and its fine screen work had always imposed demands on Shenval, taking up time and attention to print and bind. ‘Motif had to wait its turn down at the printing works,’ says Lawry, ‘and that could be maddening.’ There were lengthening gaps between its publication, and the issue with Mosley’s article was much delayed.

Shand seemed to lose interest and contributors went unpaid. ‘It is clear that we cannot continue to produce Motif with the present irregularity of appearance,’ writes McLean in a note to Shand in December 1964. ‘I am not prepared to give it up without a struggle to save it. There is still no magazine in Britain catering for all the visual arts in visual terms.’ It was a disheartening time for McLean. Shand was absent for long periods and hard to pin down when he surfaced. It emerged that he was ill, and he died suddenly in November 1967 of a coronary thrombosis. The final issue, no. 13, originally planned for publication in early 1965, came out at the end of 1967 as a tribute.

‘There was a time,’ notes Glaser, ‘when idiosyncratic publications like this that were the vision of individuals could find a way to survive. It’s just charming to see how entertaining, instructive and interesting they were able to be. Anybody who read Motif back in the 1960s would remember it.’ Four decades later, the magazine’s carefully balanced coverage of art and design still looks looks intelligent and challenging. Motif stands as a vivid reminder of a refined and now fading publishing culture dedicated to high standards of inquiry and writing, and with a passion to explore the aesthetic possibilities of printing and the pleasures of the visible world.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, London

First published in Eye no. 62 vol. 16 2006

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.