Winter 2014

Truth to photographic materials

Platon specialises in arresting portraits of the world’s movers and shakers; now, with his People’s Portfolio, he’s aiming to tell another side of the story

The setting is a Russian hotel room. Blackout curtains further subdue the light from the grey Moscow sky. For the handful of people in the room, the next four hours mark the culmination of months of planning. Cellphones are made safe from monitoring. There’s a knock at the door. It opens, and in walks Edward Snowden, ‘the most wanted man in the world’. There to greet him are a team from Wired magazine, and Platon, portrait photographer and now, with the creation of his new nonprofit foundation – the People’s Portfolio – a photographic philanthropist.

The resulting cover for Wired’s September 2014 issue is another in a seemingly endless flow of arresting images of the powerful, and more recently, the powerless. Platon’s work, for Rolling Stone, The New York Times Magazine, Vanity Fair, Esquire, GQ, The Sunday Times Magazine, Wired, Time and The New Yorker, has captured wisdom, pride, hubris, sadness, struggle, fame and infamy on the faces of those that have sat for him. He’s been awarded first prize in the World Press Photo Contest (in 2007 for his portrait of Putin) and become a member of the Global Leadership Council for the World Economic Forum.

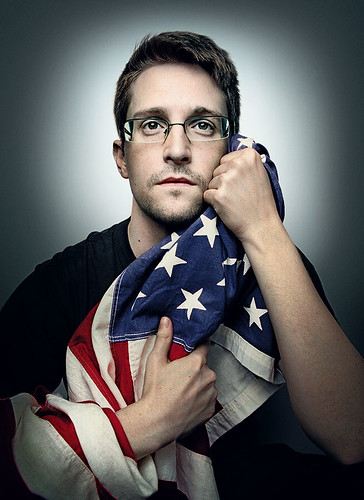

Edward Snowden, 2014. The image, for the US September edition of Wired, shows Snowden clutching the same United States flag that Platon used for his cover portrait of Pamela Anderson for the January 1998 edition of George. Platon says: ‘His glasses had broken and one pad on one side was missing, so they kept slipping, and he kept tipping them up with his finger.’

Top: Platon with George Lois, former art director of Esquire, 2012.

Yet photography was not the profession Platon considered entering. His father, Jim Antoniou, an architect and town planner who worked frequently in the developing world, was also an accomplished illustrator. Among other things, he produced a series of covers for the books of Nikos Kazantzakis, commissioned by Alan Fletcher. Platon would later work with Fletcher during the development of his debut monograph Platon’s Republic in 2004. The book was published by Phaidon, for whom Fletcher was a consultant (see ‘Remembering a graphic artist’ in Eye 62).

Despite his father’s mentoring, he wouldn’t spend his future in architectural practice. ‘I wasn’t good enough at mathematics to be an architect, or so I thought.’ What his father certainly had helped him develop was an understanding of form and texture, and a sensitivity to the principles of Modernism. ‘The idea of being truthful to your materials was embedded in my brain. I still think of what I do not really as photography but as a continuing journey of those principles, showing truth in your finished work. If someone’s character is suspicious or meditative or even aggressive, that’s the truth – the soul and spirit of the project. You’ve got to find it and bring it out.’

Platon (born Platon Antoniou), studied graphic design at London’s Central St Martin’s (now UAL Central Saint Martins). He rubbed shoulders with the emerging talents of the time – Jonathan Barnbrook, Peter Anderson and future Tomato partner Graham Wood. He pored over the poster designs of Fletcher, Saul Bass and Paul Rand. And then he picked up a camera. ‘I photographed a friend of mine as part of an assignment. There was this rush of energy between us and I thought, “This is an event.” All I did was pick up a camera. But it created a hyper-magnified version of what life is.’ He immediately fell in love with the process. ‘Although I wasn’t a great designer, I could create great imagery which still had a sense of balance and order, tone, contrast, colour.’

His graphic studies were far from wasted. They helped his early photographic work, especially on magazine assignments where his respect for designers led him to compensate for the physical requirements of a magazine layout during the shoot. ‘Most photographers thought, “It’s a beautiful photograph, don’t mess with it, it belongs on a gallery wall”. But it’s not on a gallery wall – it’s in a magazine.’ Platon would visualise the page or spread in camera, before an art director got involved.

After St Martin’s, Platon studied photography and fine art at the Royal College of Art and did some work for British Vogue. Then, to his surprise, came an invitation to go to New York and work for the late John Kennedy Jr at George magazine. When the call came, Platon thought it was a prank. Propelled to the centre of US politics and celebrity culture, Kennedy’s brief to him was simple: find the truth of the subject, whoever it is. Before each sitting, Kennedy gave Platon an envelope to pass to the subject. In it was a handwritten note. Platon says: ‘The essence of the note was: “I know you’re being photographed by someone that you’ve never heard of. This has no experience in dealing with someone of your stature, but he speaks the truth and he’s here to capture you as a human being. If you value what I’m trying to do with this magazine it would mean the world to us that you give this young man your time and your sincerity.”’

In 2008 Platon was contracted to The New Yorker as staff photographer, a role previously filled by Richard Avedon. ‘They needed someone who they felt could handle the large-scale portfolios that come out once or twice a year,’ says Platon. ‘And they decided that instead of taking on someone big, they could take on someone … they could mould.’

The ‘Little Rock Nine’, The New Yorker, 2010. In 1957 they made history by enrolling at Little Rock Central High School, previously an all-white institution. From left: Jefferson Thomas, Minnijean Brown-Trickey, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Elizabeth Eckford, Carlotta Walls LaNier, Terrence Roberts, Thelma Mothershed Wair, Melba Patillo Beals and Ernest Green.

In at the deep end

Elisabeth Biondi, visual editor of The New Yorker, threw Platon in at the deep end. One of his first assignments, a celebration of the civil rights movement, went on for nine months. He spent time with the Little Rock Nine. He sat with the McNair family, whose daughter Denise was killed by a bomb planted by a member of a Ku Klux Klan splinter group outside the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. And he spent a day at the home of boxer Muhammad Ali. Midway through the project, Platon had a crisis of confidence. ‘I just thought, I’m not qualified. I’m too young, I’m not black, and I’m not even American. I called up Elisabeth, and I said, “Look, I can’t do this job. It would be patronising to try and tell their stories.” And she said, “Let go of your mind, and use your heart. Be a human being. If you have compassion, you can tell anybody’s story.”

The status of his subjects can create problems. His energetic portrait of former US President Bill Clinton for Esquire in 2000 was taken during the last 30 seconds of his allotted eight minutes. Indeed time, or the lack of it, also explains a good deal about his austere palette. ‘If you’re aiming to get a sense of authenticity from a person, it goes back to Modernism: there should be no distraction.’ Louis Sullivan’s dictum guides his work: ‘All you need is a sense of authenticity to your materials … You don’t know what’s going to happen until the person walks in the room. Magazines love gimmicks, but for me the whole point is to strip everything bare. Something’s going to happen. You just don’t know what it is.’

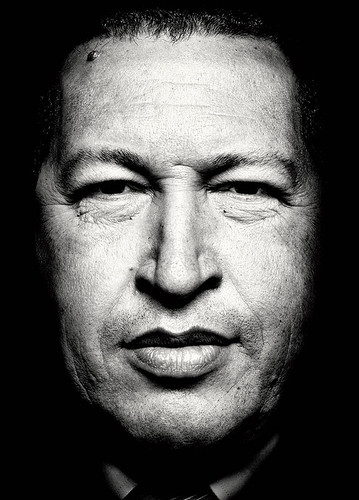

Sometimes he prefers less time – he had just 30 seconds with Hugo Chávez. Platon says he finds it difficult to sustain his concentration, and, he believes, the same is true of the majority of his subjects. He is also acutely aware of restrictions when photographing those with no power. ‘If I’m photographing a leader of the Egyptian revolution in the middle of Tahrir Square, I also only have a few minutes because in this case we’re being shot at, and this person is fighting a much more important fight than making time to pose for a picture.’ Taken as part of his assignment in Egypt for The New Yorker, his portrait of Ramy Essam, ‘The Singer of the Square’, is one of his most dramatic; both vulnerable and strong, the marks of torture burned into the musician’s back. ‘What matters to me is reaching the person. Connecting with their spirit. When you’re in the moment, I believe it, and I will die for it. It’s 100 per cent all-in committed.’

Hugo Chávez, Time magazine, 2013. Platon’s 30-second single-frame shoot of the late president of Venezuela was short even by his standards. Platon: ‘The less time the better. The more intense it is.’

Today, Platon is giving much of his energy and time to his philanthropic efforts. ‘When I started out I was definitely seduced by power. But I had a deep conviction going back to my father who worked most of his life in the Third World. He would come back from Pakistan or Kenya or Nigeria or Egypt, and he would tell us stories of how hard life can be, and how privileged we are, so I always had a very honest opinion of how imbalanced the world is.’

The idea of the foundation started with a conversation backstage at the World Economic Forum in 2011, where Platon was speaking about his portraits of world leaders and The New Yorker civil rights project. ‘A person of influence approached me after the talk and they said: “I sat and watched your presentation, and you’re a mess. You’re all over the place. You’ve got no discipline, and you’re completely ineffective. But there’s something about what you’re doing that I’ve never seen before, and I want to help you focus it, and channel it, and build it into something that is devastatingly effective.”’ And so the People’s Portfolio was born.

Through its auspices, Platon is turning his lens on people who have been robbed of power, those who are standing in the face of oppression to demand their civil or human rights. In Platon’s eyes, the People’s Portfolio is about establishing a new set of cultural heroes and throwing light on the powerless, the oppressed, the underdogs. He has photographed Burmese victims and exiles, Egyptian revolutionaries, and those fighting against oppression in Russia. He photographed Aung San Suu Kyi the day after her release.

Uncomfortable truths

‘The problem is that the big stories are not being told, and if they are, they’re not being told properly. So I thought, why don’t I find a new system? Instead of relying on the magazines’ failing infrastructures, why don’t I create my own? I’ll raise my own money and access the people I know that have power, influence and money. I’d never raised a penny before. I recruited an incredible board of directors, and we’re creating this new platform. We’re forming partnerships with NGOs who have all the stories but have no access to the media and also have no money to tell the stories either.’ Platon has shot portfolios in collaboration with Human Rights Watch, The New Yorker, the National Center for Civil and Human Rights, ExxonMobil and the UN Foundation. Platon’s reputation means he can pick up the phone to many of the world’s foremost editors. ‘I tell them: “If I supplied you with a portfolio that cost money to make and I give it to you for free, will you run it big?” and there are not many editors who can turn that kind of offer down.’

The People’s Portfolio is still in its infancy. ‘I’m constantly fundraising and being a cheerleader,’ says Platon. ‘We’re not solid yet, nor will we be until this thing is unstoppable, so right now I have to give it everything I’ve got.’ His ambition for the foundation is tempered, but set for the long term. ‘I would love nothing more than for it to become a serious platform for many storytellers to use to communicate the issues of our time.’

Platon sees his foundation as a reminder of uncomfortable truths. ‘If I’m photographing someone who’s done bad things to people, I’m not there to judge. If I get the picture right, the picture will show it. If you say “I’m being truthful” and you’re talking to someone like Putin, all he cares about is the truth, too – his truth! I don’t want to judge him by consciously making him look bad. If I believe I am being truthful, then it all shows.’

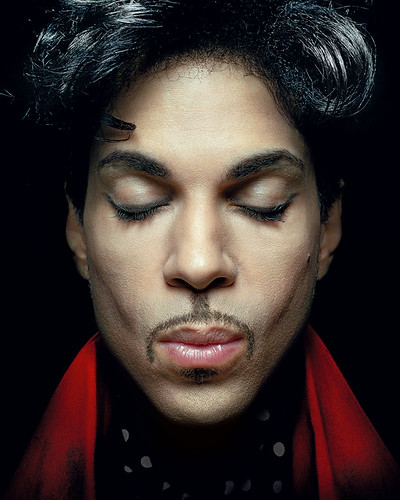

As a boy, Platon used to fantasise about being a pop star, being part of something. ‘I never made it as a pop star, but through photography I am part of what’s going on. Part of the times. That’s what we all live for. We’re all trying to move people, to remind people of what it is to be alive.’

Prince, 2004. ‘This shot was taken backstage before he went on to face an audience of 25,000 – he was incredibly serene, his nerves were steady. He seemed to be utterly in his element.’

Patrick Baglee, compositor’s son, New York

First published in Eye no. 89 vol. 23 2014

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 89 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.