Spring 1992

Visual aids

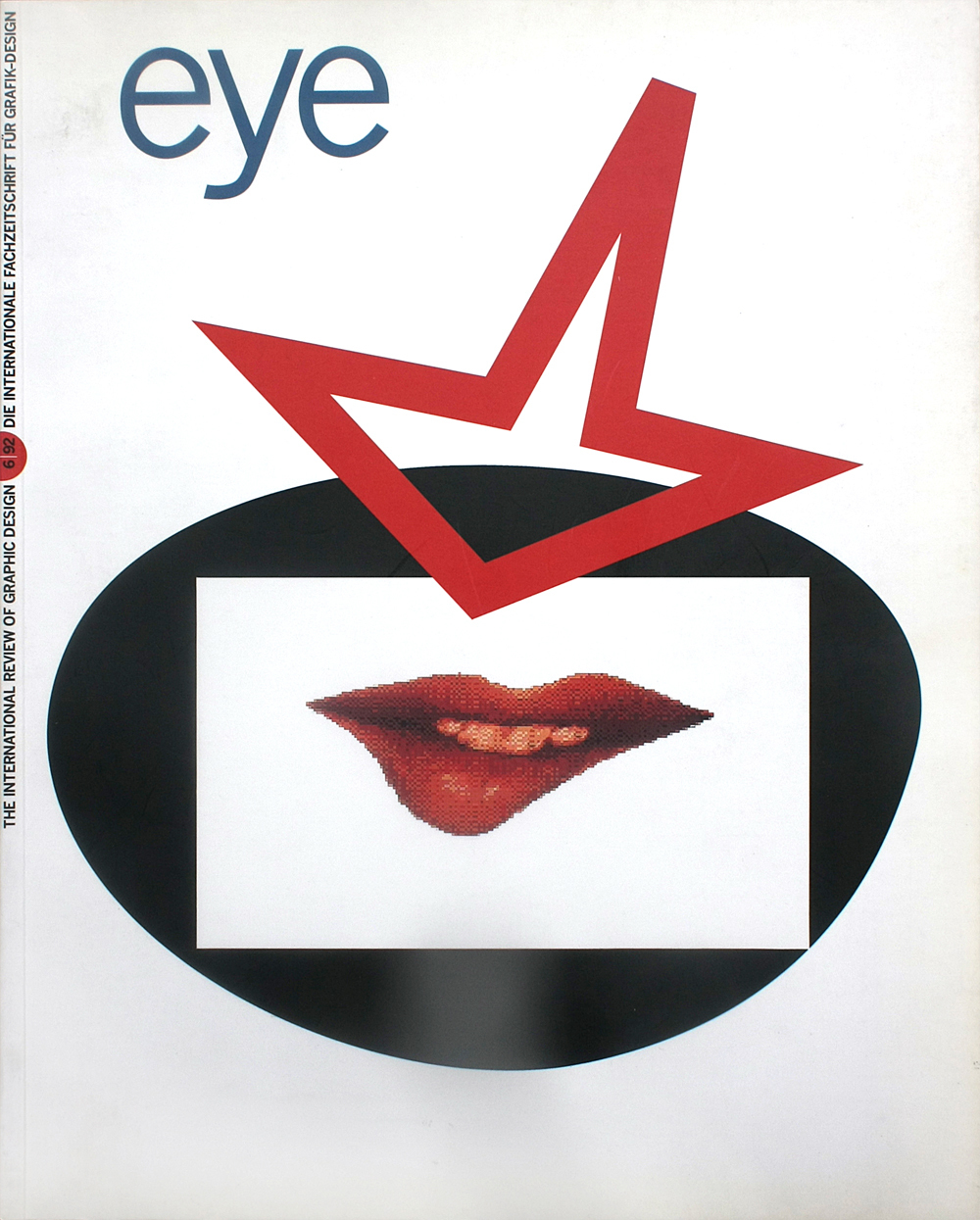

Poster campaigns have an important role to play in AIDS health education. But what makes an effective poster? Eye analyses international approaches and looks at the work of the New York activist group Gran Fury.

Posters have played a major role in AIDS education. All over the world, government agencies have produced posters with a wide variety of aims and objectives. Poster campaigns vary according to the nature of the institutions which produce them, and according to local needs. Medical information and social policies change over time, while concrete experience of the epidemic varies greatly within and between different parts of the world. Thus, in the countries of northern Europe, the majority of cases of HIV (the virus that damages the immune system) and AIDS (the life-threatening conditions from which the body may then be at risk) are among gay men. In the south of Europe, most cases are among drug-users and their sexual partners.

In most countries, however, there has been a marked contrast between national, state-funded AIDS education aimed at the general public, and education produced by charities and community-based organisations targeting specific social groups. Governments of all political persuasions have evidently been reluctant to provide frank safer sex materials, for fear, it is often claimed, of ‘offending’ potential voters. Indeed, one of the strangest aspects of the world-wide history of AIDS education has been the repeated assertion that condom education might ‘promote’ promiscuity, or that the provision of needle-exchanges for drug addicts might ‘promote’ the use of drugs. Thus most official government campaigns have tended to be vague and euphemistic, relying on scare tactics and the pretence that everyone is at equal risk. Such campaigns have caused much confusion, while the needs of those most at risk are largely ignored.

This is why it has proved necessary for non-government organisations to produce their own materials addressing topics and population groups which governments have proved unwilling or unable to face. The major problem, of course, is sex. Government posters tend to recommend either monogamy or celibacy as the ‘correct’ moral answers to the problem of HIV infection, while overlooking the needs of lesbians and gay men, the young, and the sexually active. It is only at arm’s length that government money can be used to support more practical and pragmatic approaches. Government agencies usually employ the services of large, successful advertising agencies to produce their materials for the general public, and these are marketed very much in the same way as any other commodity. It is only in the voluntary sector that more imaginative and demonstrably effective strategies have been undertaken.

The result has been that different population groups have received very different kinds of AIDS education posters. Advice to heterosexuals is frequently unclear and indirect. Materials produced by and for gay men, on the other hand, have tended to be far more explicit and supportive. Posters produced for racial and ethnic minorities tend to be dull and overly didactic; injecting drug-users and prostitutes are often depicted in highly stereotypical ways, as if they were the problem, rather than HIV. Like many other areas of health education, AIDS posters frequently lapse into over-literalness, as in the advertising of services provided by charities and hospices. Nor should it be forgotten that in many countries AIDS education is limited by laws defining what is and is not ‘decent’. Hence the repeated use of metaphors such as bananas and socks, which have an insulting tendency to treat adults as if they were children who must not hear the word ‘s-e-x’.

The best AIDS posters have tended to be the simplest. The Swedish RFSL support service’s ‘Take care – be safe’ campaign took a single, simple phrase and used it in a wide variety of contexts. In Germany, the Deutsche Aids-Hilfe has also produced excellent posters. These have emphasised shared gay community values in the face of the challenge of HIV, while frequently drawing on local cultural associations within the history of photography, such as the portraiture of August Sander in the 1930s. Australia’s Victoria Aids Council and the Aids Council of New South Wales provide examples of carefully targeted and researched work, which has been especially attentive to the generally neglected needs of gay teenagers. The results of such neglect can be seen in the Bay Area of California; while the general rate of new cases of HIV among gay men has fallen, this has been much less marked among the young, who have rarely been addressed. Hence the significance of the San Francisco Aids Foundation’s poster, which literally wraps two young gays in the American flag, wittily drawing attention to the way in which the group is usually excluded from supposedly national campaigns.

In Africa and elsewhere in the Third World, where heterosexual transmission accounts for the majority of cases of HIV and AIDS, the best posters have drawn on local cultural traditions. And everywhere the need to use condoms has generated a host of differently styled messages, from the bizarre Swiss vision of an ideal village nestling safely inside a vast condom, to a parallel epidemic of Swedish cartoon penises. As this shows, the jokey, ‘ho ho!’ approach has usually been less than successful. Many poster campaigns have also revealed the limitations of documentary photography in health promotion. In the United States, with the worst epidemic on earth, but no coherent national AIDS education, AIDS activists such as Gran Fury and the late Keith Haring have produced the most directly confrontational posters.

Yet posters are in themselves only a small part of effective HIV/AIDS education. Too often it seems that posters are produced by state agencies in order to be seen to be doing something, rather than in response to actual, concrete needs. At their best, AIDS education posters can work as triggers – reminders of the epidemic at times when, and in places where, we might prefer to forget it. It is therefore vitally important that all such campaigns should be properly evaluated, in order to learn promptly from past mistakes and successes. Sadly, this has rarely been the case to date. As we move nearer the end of the century, and as the epidemic worsens in those groups where HIV was widely transmitted in the years before it was even known to exist, it is more important than ever that five fundamental principles should be more widely respected and observed.

First, the need for honesty. People are entitled to clear, unambiguous information, which takes them and their lives seriously. Second, all poster campaigns should be targeted at specific groups, since few will identify closely with messages designed for an abstract, average ‘general public’. Third, information should be as widely accessible as possible. There is no time for obscurity. Fourth, posters should be as supportive as possible of people’s emotional and sexual needs. The history of health education demonstrates the inevitable failure of campaigns that try to frighten people into changing aspects of their behaviour; the continuing failure of anti-smoking campaigns for the young is a case in point. Finally, posters should try to combat the ignorance and prejudice which continue to surround so many aspects of the epidemic, making both prevention and care unnecessarily difficult.

Effective HIV/AIDS education does not involve long lists of ‘dos’ and ‘don’ts’. On the contrary, it involves helping people to make choices, while respecting that we all have different sexual needs and pleasures. For such work, we need intelligent, socially sensitive graphic artists who are willing to collaborate closely with community-based organisations that best understand local needs. Much depends on our continuing to find them.

First published in Eye no. 6 vol. 2, 1992

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.