Autumn 1992

Your system sucks!

The flight from Modernism left a yearning for graphics that were rough, real, unaffected and believable. At some point, though, the downtown poster hardened into a convention

Ambiguity has always played a role in New York’s street ephemera. Downtown in lower Manhattan, among the languishing galleries and real-estate developments of the East Village, and under the lofts south of Houston Street, the posters are layered on one another like the pages of in a book of subplots and subthemes, in which one character or another may take precedence for a moment, but will soon retreat to an underlayer. It is a book in which the pages are free to move around.

I remember being surprised at the impenetrable quality of New York’s graffiti. None of it was readable, as it was in my home town of San Francisco. It was neither genital or political, and it didn’t make sense to me because I was not a part of the culture that had created it. Much of the posterisation of lower Manhattan today is interesting for that very reason: you don’t get it right off. As members of a society hammered by the 15-second media buy, we are worn out by instant messages, and we find the ambiguous intriguing.

FRENZY OF POSTERISATION

Ambiguity is only part of the conversation, though. In the late 1980s and the waning years of the Bush administration, political posterisation became frenzied. Whether the work was created by one angry person with a copier or was the effort of a publicly funded foundation, the focus was dissent. The bitter battles over Tompkins Square Park’s encamped homeless produced an entire genre of caustic, hard-edged comic book graphics; the struggles over abortion led conceptual heavyweights like Barbara Kruger to design the iconic “Your Body Is a Battleground”. Artfux, a New Jersey guerrilla group (reputed to be a group of one) systematically defaced billboards advertising alcohol and cigarettes with the intensely satisfying multiple repetition of the phrase, “We have determined that your whole system sucks”.

The Gulf War, gay pride, AIDS: the roster of political causes was emblazoned on the temporary plywood of construction sites in SoHo, and on the streetlights and telephone poles of the East Village. These posters were a backlash, a response to the inhumane interests of corporations, to the terrors of police tyranny and to the pain of homelessness. But then another voice joined in.

When was it that the downtown poster became a design convention? For that is what it has become: a convention of unconventionality. Just as Futurism and Dadaism are accepted avant-garde styles for “cutting edge” graphic design, so is the downtown poster becoming the accepted visual language of the real.

Such posters have been around since the 1940s. In the Village of the 1950s, poets pasted their ambiguities on the signposts of MacDougal Alley, as Jackson Pollock spread his canvas on the ground and his neighbours looked down and shook their heads. Today, design students troop uptown to see Pollock at the Museum of Modern Art, but they get their poster fix downtown, as they stand in front of Dean and DeLuca’s food market waiting for their cappuccino to cool. They return to their Macintoshes bristling with hubris, ready to make statements about fur, the planet or gay-bashing. They have been educated in the stylistic downtown methods: the copier, the typewriter, the comic. Pollock is history, and as such, is awarded respect. But the posters are inspirational.

Why are these techniques considered valuable now, when they weren’t in earlier years? Why does type designer Tobias Frere-Jones spend hours trying to reconfigure the software of his printer so that his next face can emulate the dirt and fill-in and randomness that a copy of a copy of a copy will produce?

LONE WOLVES AND COWBOYS

The flight from Modernism has left a yearning for the rough, the real, the unaffected, the unstreamlined, the believable. Perhaps, too, the post-modern design sensibility is soothed by a medium so directly vernacular, so different and so refreshing to eyes wearied by a lifetime of the German, Swiss and Dutch. But I also sense a desire for direct causes and direct effects, for individual control over one’s life and work, and for a sense of personal effectiveness in an era in which two days of televised Bill Clinton leave one overwhelmed by the picayune realities of contemporary government. I believe the desire to imitate the downtown poster is a Romantic desire, in the sense that Frankenstein is a Romantic work of fiction and the lone wolf, the cowboy and the fire-fighter are Romantic heroes. They fight their battles, feel the rush of adrenalin, give their all to a cause, and then move on.

“Moving on” is important. Because that’s what separates the style from the real; Byron from the Greek; Hemingway from the Spaniard. Someone had to stay and patch up the place long after Hemingway had moved on to smoke cigars in Havana. And so it is with the political posterer or ambiguous symbologist of lower Manhattan. These people stay with it, whether abortion rights or AIDS are fashionable or not.

Designers schooled in the downtown style, however, will move on. For designers chase the cutting edge, whether they purport to or not. Give me a graphic designer who humbly sets forth perfect communication as the be-all and end-all of design and I’ll show you a semiotician, not a designer. Designers love the new, the tactile and the systematic, and the downtown poster provides an instantly recognisable system of mores, cultural values and social principles.

Designers will tire of manipulating Courier on their double-page monitors. They will realise that everyone else is doing it, that’s it not as racy as it once was, that, in fact, downtown is dull, and they will leave it, as the droves of interior designers who descended on Santa Fe, New Mexico left like swallows from Capistrano a few years later. Santa Fe, was changed by the influx – it now carries the patina of voyeurism – and the downtown poster, too, has been changed. The Heisenberg principle applies just as well to style shifts as it does to physics: the act of observing an experiment alters the experiment.

On the plywood hoardings of lower Manhattan, posters that use the imagery of politics are now trying to sell more than ideas. The angry image and the unbridled epithet are selling a new album. The ambiguous is selling an outfit. The flagrant and the feminist are selling a newspaper. At its most basic level, the downtown style wants you to pay $15 at the door of the music place CBGBs. At its most mediated, it tells you that Kenneth Cole shoes, or Esprit socks, or Madonna are real, are touch, are individual. The very designers who once took inspiration from the downtown narrative are now creating posters designed to sell products on the same streets. And this consumerist voice adds its timbre to the mix, offering up what looks and feels like the real, but what is, in actuality, merely the style. The political image and the ambiguous image are both now operating in the service of the stockholder and the shopkeeper.

ICONS OF THE REAL

So the downtown poster has become commodified. For the student who railed for social justice becomes the designer who works for money, and that designer holds the downtown poster as an icon of the real. Even the American Institute of Graphic Arts, that wellspring of design appropriateness, has mounted a travelling exhibition celebrating the freshness and responsibility of these posters. Where there is celebration there is appropriation.

The value of the real downtown poster lies not in its stylistic convention. It lies in its guts. It takes guts to be a Gran Fury, Guerrilla Girls or Artfux. It takes risk and it takes initiative and a good deal of exhaustive physical labour to create, produce and paste posters that tell a story you don’t get paid for. The value of these posters is in what they say about the human spirit, about human diversity, in a time when the media is compressing the expression of individual human experience down to eighth-grade level.

The Xeroxed pieces of paper that line the streets of lower Manhattan ask us to question authority, to question convention, to review ingrained mental habits. As designers, we bring to our clients what we have accepted ourselves, and these posters, ambiguous or political, remind us that we have to pay attention to what we accept without question.

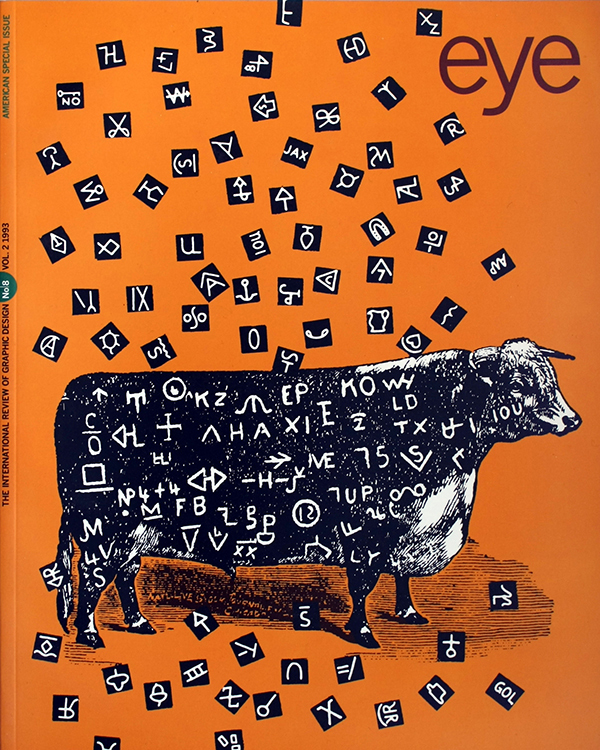

First published in Eye no. 8 vol. 2, 1993.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.