Wednesday, 11:00am

12 April 2017

Age of the female gaze

Rania Matar

Leah Schrager

Juno Calypso

Maisie Cousins

Isabelle Wenzel

Phebe Schmidt

Shae DeTar

Photography

Critique / Photography

Web Critique

Girl on Girl – a new survey of 40 contemporary photographers – raises questions about the nature of representation without necessarily answering them. Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for eyemagazine.com.

According to the subtitle of Girl on Girl, a new book of photographs selected by art critic Charlotte Jansen, this is the age of the female gaze. In the era of social media, Instagram and the selfie, more women are taking pictures of other women than ever before. Jansen’s survey (published by Laurence King) shows two or three spreads of work by 40 photographers from seventeen countries and she provides a short text about each artist – her preferred description – based on an interview.

The female gaze is a loaded term that requires a lot of unpacking and, given the book’s serious intentions, it is surprising that Jansen skates over it in her introduction. The rubric arose as a corollary to the concept of the male gaze, a cornerstone of feminist visual theory introduced by Laura Mulvey in the essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ (1975). This analysis holds that in Hollywood films, and by extension in other visual media, women are depicted passively for the pleasure of male viewers and their full humanity is denied. ‘In the past,’ writes Jansen, ‘photographs of women were made by men for a capitalist economy to favour the male gaze and feed female competitiveness.’

Phebe Schmidt, Secretly Susan, album cover, 2015.

Top: Isabelle Wenzel, Field 1, 2015.

At the most elementary level, the female gaze covers any picture of a woman not made by a man. The female gaze is a ‘corrective’, in the words of magazine editor Zing Tsjeng, who contributes a foreword, but it is also ‘multiple’, encompassing many ways of seeing. Jansen, too, emphasises this diversity of perspective. While she describes the project as ‘pro-female’, some of the pictures included may not be, she cautions – they are not necessarily about either feminism or femininity. This looseness of definition leaves the collection sailing under a flag of convenience that has no convincing theoretical foundation in its pages. And one might add that the ‘male gaze’, while useful and revealing when applied in particular cases, becomes an implausible straw man when treated as the totality and limit of male ways of seeing women, which might equally be ‘cool, dispassionate, ironic, sublime, or tender’ – terms of approval Tsjeng applies to women’s pictures – as well as many other points of view.

The photographers are as varied a group as these provisos might lead one to expect. Their work ranges from Lalla Essaydi’s images of self-possessed Arab women in ornate traditional interiors, a riposte to the nineteenth-century Orientalist painters’ objectifying gaze, to Izumi Miyazaki’s surreal and comic self-portraits with canned tomatoes and slices of bread – visualisations of the Japanese artist’s interior world with ‘no particular message to transmit to the society around me.’

Rania Matar, Brigitte and Huguette, Ghazir, Lebanon, 2014.

The photographers’ ages aren’t given (nor always is their country of origin), but a number appear in their own pictures and they are mostly young. An exception is Rania Matar, a Lebanese/American photographer now in her early fifties, whose study of a mother and daughter, Brigitte and Huguette, Ghazir, Lebanon, is a complex and emotionally compelling image of great depth and humanity. Many pictures focus on the body and take place in the private (now made public) sanctuary of the bedroom. Physical appearance and beauty is often the central concern, even in these self-directed images. Mihaela Noroc has visited more than 50 countries, photographing women she considers serene in their beauty. Marianna Rothen’s partially clad women have the dreamy, muse-like loveliness of film stars. Juno Calypso poses voluptuously in green body paint in front of a multi-panel mirror in a love hotel bathroom. ‘I have a type I photograph in my work,’ says Jessica Yatrofsky. ‘I have to make my work based on my own desires.’

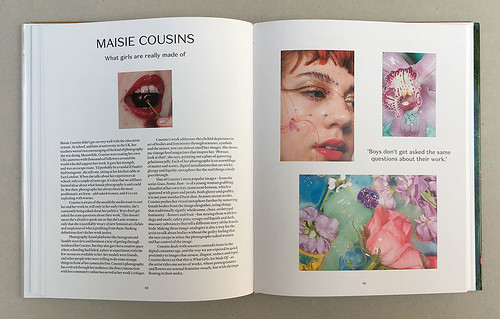

Spread from Girl on Girl showing work by photographer Maisie Cousins including an image from the ‘S.E.X.’ series, 2015; Celia, 2015; Orchid, 2016; and Untitled, 2015.

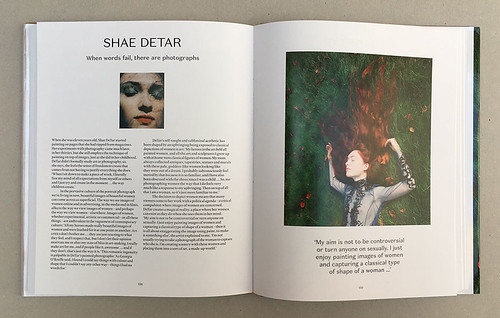

Spread showing Shae DeTar’s Most Imperfectly, 2014, and Skye, 2014.

As with any overview of this kind, Jansen’s stance as curator is inherently supportive. Although she doesn’t duck complications and contradictions when they arise from her subjects’ work and testimony, she tends to smooth over them. She concedes that there can sometimes be little difference between how a woman photographer has conceived and shot an image and how a man would do it, and then says, ‘women have the right to self-objectify and to exploit without critique, just as men have been allowed to do since the earliest forms of art emerged.’

That might sound fair, and if the women were photographing men then it would be straightforward payback (the book has only one example of this, and is largely man-free) but it isn’t much of an argument. One might even wonder whether women’s impulsion to devise images expressing their personal ideals of beauty or desire – ‘I really make art for me,’ says Shae DeTar – shows that objectification is just a natural tendency among people, irrespective of gender. On the other hand, if it is a form of behaviour instilled by a society founded on exploitation, then don’t we have a duty to resist it, assuming we believe it to be wrong?

Juno Calypso, 12 Reasons You’re Tired All the Time, 2013.

What does seem curious is that these pictures of women by women, which could venture anywhere, don’t encompass a wider range of female experiences. Why no images of female architects, doctors, teachers, sportswomen, policewomen, businesswomen, cleaners, or astrophysicists? Jansen raises the question of whether the pictures are a fair representation of women and declares, ‘Of course, they cannot be.’ Men once again provide the excuse: why should women’s photographs be any more well rounded than men’s ‘unrealistic images’ of women have been? This is an unfortunate misrepresentation of the history of photography – of photographs taken by men and women (Ilse Bing, Lisette Model, Dorothea Lange, Lee Miller, Helen Levitt, Vivian Maier, Diane Arbus, Susan Meiselas, to name just a few).

Girl on Girl is an absorbing and timely collection of pictures and it raises some important questions about the nature and purpose of representation. The most problematic images are often those that are most contemporary in their relation to online culture, where the competitive drives of capitalism, cited by Jansen, now burgeon. While some attractive women find satisfaction in the opportunity for self-display (in the cause of art), for other women these further images of unattainable allure only add to their anxiety and insecurity. Is that just their bad luck? From this angle, the uneasy and unforgiving self-portraits by Iiu Susiraja – in one she wears a crown of uncooked sausages – may be the most challenging and awkward to process in the book.

Leah Schrager, Infinity Selfies, 2016.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.