Friday, 10:45am

15 February 2013

Cold-blooded runaways

A third edition of Redheaded Peckerwood, Christian Patterson’s ravishing photobook, gives this enduring American horror story another twist. Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for eyemagazine.com.

In the world of photobooks, the American artist Christian Patterson’s Redheaded Peckerwood is something of a phenomenon. First published by Mack in November 2011, the book quickly found its way on to many best-of-year lists and, just a few months later, a second edition appeared with superior printing – not that the first edition wasn’t immaculately produced. The book won the 2012 author book award at the Rencontres d’Arles photography festival against scores of contenders. Now a third edition, with some additional changes made by Patterson, has been published. (Mack doesn’t release figures for print runs.)

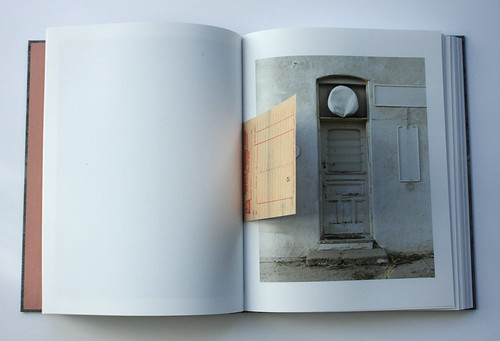

The insert is a facsimile of a receipt found in the wallet of a teenage victim. A poem by his father, the store owner, titled ‘Little Town’ is stamped on the back.

Top: ‘Burned-out Room’, Christian Patterson.

New spread from the third edition of Christian Patterson’s Redheaded Peckerwood (Mack), 2013.

I felt Peckerwood’s peculiar magnetism, too, and wrote about it for the Designers & Books website. What is it about the book that has won it such widespread acclaim in the photography world and beyond? First, there is the compulsion of its dark American crime subject. The project was inspired by the notorious case of nineteen-year-old Charles Starkweather – a redhead – and his girlfriend accomplice Caril Ann Fugate, fourteen, who rampaged across Nebraska in 1958 on a killing spree. Starkweather went to the electric chair for eleven murders, and Fugate was jailed and eventually released. Terrence Malick used the story as the basis of his cult classic Badlands (1973) and Oliver Stone produced a tenuous reworking in Natural Born Killers (1994). In 1982, Bruce Springsteen wrote ‘Nebraska’, a song about the lovers: ‘I can’t say that I’m sorry for the things that we done / At least for a little while sir me and her we had us some fun’.

Compared to these accounts, Peckerwood offers mysteriously oblique hints at a narrative rather than a sequence that resolves into a clear-cut depiction of events. Patterson explained in an interview that he allowed ‘ideas to come to me from almost anywhere, as long as they related in some way to some version of the story’ – a wide-open method of inquiry and composition. He undertook a road trip based on the route travelled by the killers and drew on a range of sources that included factual accounts in books, newspapers, court transcripts and interviews, as well as fictionalised interpretations such as Badlands. In the process of transforming these elements, he allowed his imagination free rein.

‘Broken Bulb’, Christian Patterson.

Revisiting the book, it seems as startlingly original as it did on first viewing. The images couldn’t be more disparate or at times disconnected and yet thanks to Patterson’s visual editing and sureness of atmospheric control, they meld into an experience that feels aesthetically unified, emotionally coherent and verging on mythic. Many of his pictures represent the kinds of sight the runaways might have seen as they scattered bodies in their wake: the flare of a cigarette lighter, a penknife stuck in a cracked wall, a collapsing farmhouse in the trees, a shattered door leading to the open prairie, bottle tops scattered on a filthy floor. Patterson has an epiphanic sensitivity to textures such as the inky spill of Shinola polish or the matted blue fur of a stuffed toy and his photos of banal and decrepit scenes, where every element vibrates with implication, possess a luminous purity. He also designed the book and he knows exactly where to place the cleansing whiteness of an empty page.

In the second edition, Patterson introduced some drawings to the essay booklet tucked into the back and for the third he has added four new archival photographs, uncovered during his continuing research, as well as a postcard insert, a facsimile of a message Starkweather sent to his parents after capture – the book already has other documents of this kind. These adjustments to a published work of art might seem indecisive or superfluous, but Patterson takes the view that Peckerwood, which he also exhibits as pictures, is an evolving project. A curious old photo of a poodle and someone’s shoe emerging from under a bed now falls between a picture of a house with an ominous dark mauve hue, titled ‘Day of Terror’, and a shot of a broken bulb in a ceiling light: the progression is undeniably stronger. The new pictures at the end, among them two of Fugate in custody, reinforce the book’s conclusion and help to sharpen its speculative and anticipatory passages by anchoring the story more firmly in documentary reality.

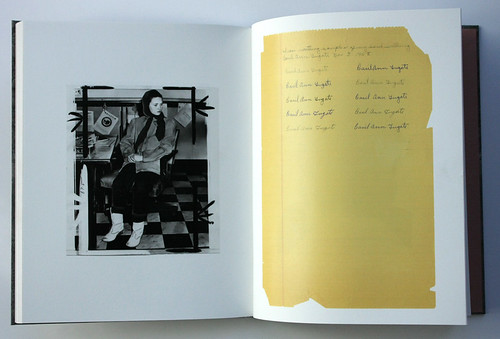

Spread featuring ‘Fruit Cake 98 Cents’ and ‘Stuffed Toy Poodle’, Christian Patterson.

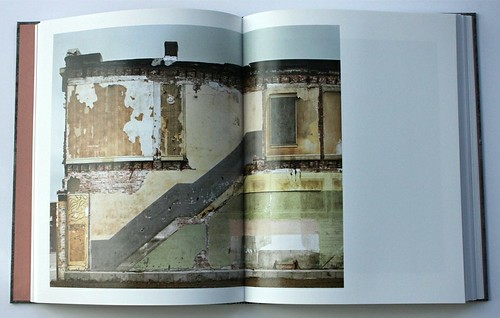

Spread featuring ‘Stairway to Nowhere’, Christian Patterson.

Peckerwood achieves a deeply satisfying balance. Its police dossier-like accumulation of evidence puts the viewer in the position of investigator circling through the pages for intimations and clues. Like other American photographers, from Walker Evans to William Eggleston (with whom he worked), Patterson loves signs and he includes several paintings of lettering in vernacular styles. This novel conflation of visual registers expands the possibilities of the photobook as a medium. Then there is the ravishing aesthetic quality of many of the images, which reviewers have tended not to dwell on. My guess is that the book’s popularity stems as much as anything from the ambivalent kind of beauty it finds in the spaces between the disturbing events of this enduring American horror story. It’s both exquisitely suggestive and as searing as a newsman’s flash bulb.

Rick Poynor, writer, founding editor of Eye, London

Christian Patterson, Redheaded Peckerwood, third edition, 2013.

Published by Mack, £40. Printed by Optimal Media, Germany.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and back issues. You can see what Eye 84 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.