Wednesday, 9:30am

18 April 2018

Different kinds of marginal

Diane Arbus’s unsparing images retain their power to discomfit. Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eyemagazine.com

In a famous essay, ‘America, Seen Through Photographs, Darkly’ in On Photography, Susan Sontag rips into Diane Arbus’s pictures. ‘Her work shows people who are pathetic, pitiable, as well as repulsive, but it does not arouse any compassionate feelings.’ Sontag proceeds to argue that much of modern art has dedicated itself to ‘lowering the threshold of what is terrible’ and accustoming the audience to the ‘rising grotesqueness in images’. The false familiarity viewers then feel with the horrible deepens a sense of alienation and makes them less able to react when confronted by actual horrors in everyday life.

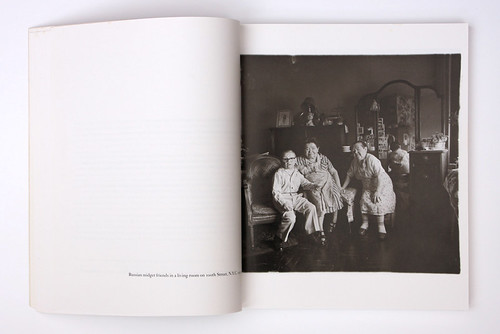

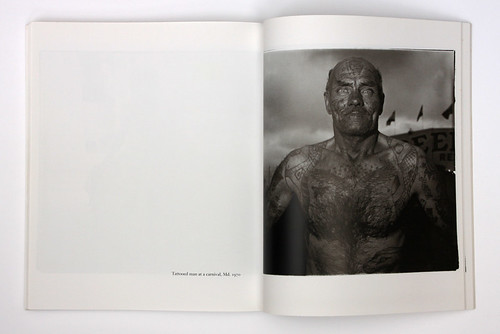

I was reminded of the essay on walking into ‘Another Kind of Life: Photography on the Margins’ at the Barbican Art Gallery, London. The first room presents six photographs taken by the acerbic American photographer between 1963 and 1970, the year before she died: three Russian midget friends, a tattooed man at a carnival, a naked man being a woman (in the words of Arbus’s title), a woman albino sword swallower, a waitress wearing an apron at a nudist camp, and a young black man and his white pregnant wife.

Spread from Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph showing Russian midget friends in a living room on 100th Street, N.Y.C., 1963.

Top: Installation view ‘Another Kind of Life: Photography on the Margins’, curated by Alona Pardo, at the Barbican Art Gallery. Photo: Ian Gavan / Getty Images for the Barbican.

The selection is more severely edited than the displays for other photographers in the show and it’s unclear whether this is to bolster the impact of the six pictures as introductory icons of different kinds of marginality, or because only a limited number were available to the gallery (all borrowed from a national collection). Apart from the nudist, the pictures feature in the Aperture monograph Diane Arbus (1972), which is still in print and remains a cornerstone of her reputation – Sontag was reacting to the book in her essay.

Much of ‘Another Kind of Life’ is devoted to images of teenage and youth rebellion and the experiences of transgender people and cross-dressers, and the spirit of these pictures leans towards the assertion and celebration of identity in the face of social rejection. With Arbus, though, there is always troubling ambivalence. What did she really think about the tattooed man, who offers his swarthy flesh to the camera like a bright-eyed emissary from a stranger world, or the mixed-race couple (top), who stare into the camera defiantly, daring the prejudiced to question their relationship? The woman’s cat-eye glasses, beehive hairdo and heavy jaw electrify the picture, giving her a look of hardness and oddity. In a text assembled for her posthumous monograph, Arbus points out the gap between how people try to look and how they actually appear to others: ‘You see someone on the street and essentially what you notice about them is the flaw.’ She identifies this shortfall and documents it without mercy.

Diane Arbus, Tattooed man at a carnival, Md., 1970.

The flaw in Sontag’s critique is that she is so judgemental, dismissing Arbus’s subjects as ‘pathetic, pitiable, as well as repulsive’. This is not simply a matter of how Arbus portrays people; it appears to have been Sontag’s personal view and her patrician distaste says more about her than them. Like Arbus, she surveyed these fringe-dwellers from a vantage point of able-bodied, financially secure privilege. It’s hard to imagine a contemporary audience, hyper-aware of disability issues and transgender rights, presuming to assess the portraits in the same reductive terms. For Arbus, the ‘freaks’ and nudists were ‘terrific’ subjects pure and simple, and she freely acknowledged that photographing them excited her. ‘Freaks were born with their trauma,’ she said. ‘They’ve already passed their test in life.’ The worst has happened and they have no choice but to live with it. But whether or not Arbus felt any compassion when photographing the midget friends, there is still great pathos in their sense of camaraderie.

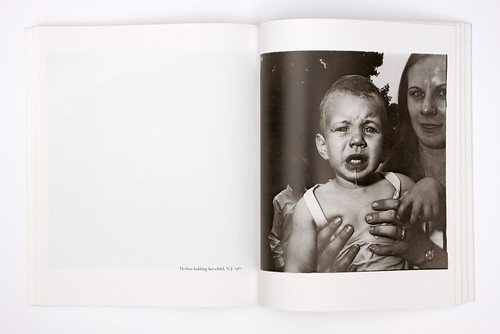

People in Arbus’s pictures are never shown in an unambiguously positive light, as a kinder photographer might do. How did she get the naked man posing as a woman to present himself with such vulnerability in this squalid room? It’s hard to believe that the picture turned out like he would have wished. Arbus could make a crying baby appear sinister, ruthlessly enlisting the child’s mother as accomplice and betrayer. A boy in Central Park clutching a toy hand grenade looks like he is in the grip of a psychotic episode; there isn’t a particle of tenderness here. The pictures are as unforgettable as they are ethically dubious, though later photographers such as Roger Ballen and Bruce Gilden went much further in their pursuit of freakishness. Arbus was one of the first photographers I admired and returning to her work, its voltage is undimmed. Considered purely as images, rather than as progressive social documents, the six pictures are some of the finest in the Barbican’s show. It’s a measure of Arbus’s unsparing eye that viewing them is a queasy experience even now.

Diane Arbus, Mother holding her child, N. J., 1967.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.