Friday, 12:00pm

25 September 2020

Godard becomes ‘Godard’

In 1961, the new wave director posed for a German fashion photographer. The publicity pictures that followed are as self-reflexive as his films.

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eye magazine.

The British film magazine Sight & Sound has launched a series of special issues presenting articles from its archive about the auteurs of cinema and the first is devoted to Jean-Luc Godard, one of the medium’s most innovative directors. The cover photograph, a portrait of Godard by the German photographer Franz Christian Gundlach, is aptly chosen. It was taken in 1961 for Film und Frau magazine when Godard was in Berlin to present his third feature, Une femme est une femme, at the Berlin film festival.

From the early 1950s, Gundlach specialised in fashion photography and Film und Frau (1949-69) was a regular outlet. His sensitivity to sartorial style and to the construction of the model’s pose are obvious in the picture. Sight & Sound cropped the photograph for impact, but the studio backdrop is still fully apparent. Gundlach makes great play of this device, even allowing the roll of paper to obscure Godard’s left foot. In the original picture (above), the normally concealed roll dominates the image as a vertical shape and Godard is surprisingly small within the surface area; behind the roll is a second empty backdrop, which becomes the frame. The picture deftly exposes the mechanics and artificiality of its making, while still presenting its well dressed, slightly mysterious subject (note the dark glasses) as a figure of seriousness and substance. Meanwhile the subject, then in his early thirties, already looks like a natural at playing the game of self-presentation for the camera’s lens.

Sight & Sound special issue on Godard. Photograph: F. C. Gundlach. Design: Chris Brawn.

Top. Godard by F. C. Gundlach, 1961. F. C. Gundlach Foundation.

Was the picture’s concept a happy accident, an ingenious response to visually routine subject matter (compared to Gundlach’s usual elegant models), or a piece of image-making of considerable insight and prescience, as its use on Sight & Sound as visual summary now implies? The famous jump cuts and other devices in À bout de souffle (1959) had introduced a critic turned film-maker prepared to play fast and loose with the conventions of film language, but Godard’s most audacious Brechtian subversions were yet to come. Was Godard perhaps a partner in conceiving the image? He was clearly, at the very least, a willing accomplice. One curious, time-bound and possibly random detail is the folksy and far from stylish wooden chair, which forms the only substantial prop (there is a barely discernible folded airmail letter in Godard’s hand). Today, closer attention would be given to selecting a signifier more in keeping with the picture’s purpose and tone. But perhaps the chair was intended to function as an intrusion of blunt reality into the pictorial artifice.

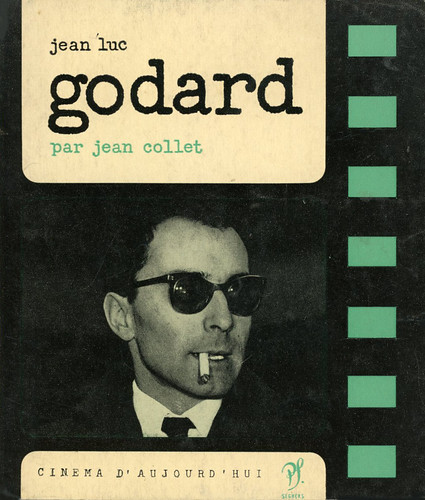

Jean-Luc Godard, published by Seghers, 1963. Photograph: Yvon Beaugier. Design: Jean Fortin.

In the early to mid-1960s, Godard became a perfect avatar of himself in photographs. The pictures that fascinate most today, embodying an ideal of French cool (though he was half Swiss), are portraits made for publicity purposes. Photographed unawares on set, directing his films or talking to actors, with a cigarette jammed in his mouth or dangling from his hand, Godard always looks dapper in well cut clothes. Sometimes he is caught in moments of intimacy, for instance with his star and wife, Anna Karina. Those pictures are more ordinary. In a photo from Télérama magazine, used on the cover of the first French study of his films, Godard becomes ‘Godard’. The shot was most likely taken impromptu in public when he knew he might be photographed. Emerging from the darkness wearing the sunglasses seen in Gundlach’s portrait and smoking a cigarette, Godard is steely, alert and inscrutable, like a secret agent of cinema.

Photograph: Philippe René Doumic, 1960s.

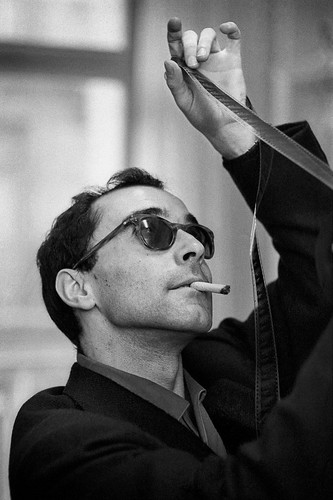

The definitive photograph of Godard in these years is Philippe Doumic’s portrait of the director immersed in his medium. Godard holds aloft a long ribbon of film, supposedly to examine its frames, though the smoky lenses of his glasses would have made that difficult. A burning cigarette protrudes from his lips just centimetres away from the precious film strip. On earlier viewings, I have assumed the picture to be a work scene because of its informality. Yet the portrait is clearly staged. In a variant from the same session, Godard holds the strip in front of him, but the pose is wooden, his expression too blank, and there is little sense of the director as a cerebral connoisseur of filmic form, as there is with the classic picture.

Photograph: Georges Pierre, 1960s.

The final pictures shown here come from a studio session with Georges Pierre in the mid-1960s. One of the photos, which became a frontispiece in Cahiers du cinéma’s exhaustive Godard au travail: less années 60 (2006), shows Godard scratching his head. A contact print featuring this picture and a more widely seen variant of the gesture (above) surfaced on the Mubi film website. The film-maker seems most at ease, most like Godard, as we think of him, in the studies where he can articulate himself as an image for media consumption with the aid of a cigarette. In a less widely seen shot, apparently from the same session, though not on the contact sheet, Godard splays his fingers and prods at his eyes, as if to clear away specks and see the world more clearly. With the omnipresent smouldering cylinder mostly cropped out of view, this became the cover portrait for Godard (Le cinéma) (2006). Godard’s unreadable expression is a performance – a simulation of idiocy, indifference, boredom? – rather than a reflection of genuine emotion. The eyes stand for the director’s vision, the cameras he will use to record it, and his transaction with the viewer.

Godard (Le cinéma), published by Gallimard, 2006. Photograph: Georges Pierre, 1960s.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.