Autumn 2013

If not for design …

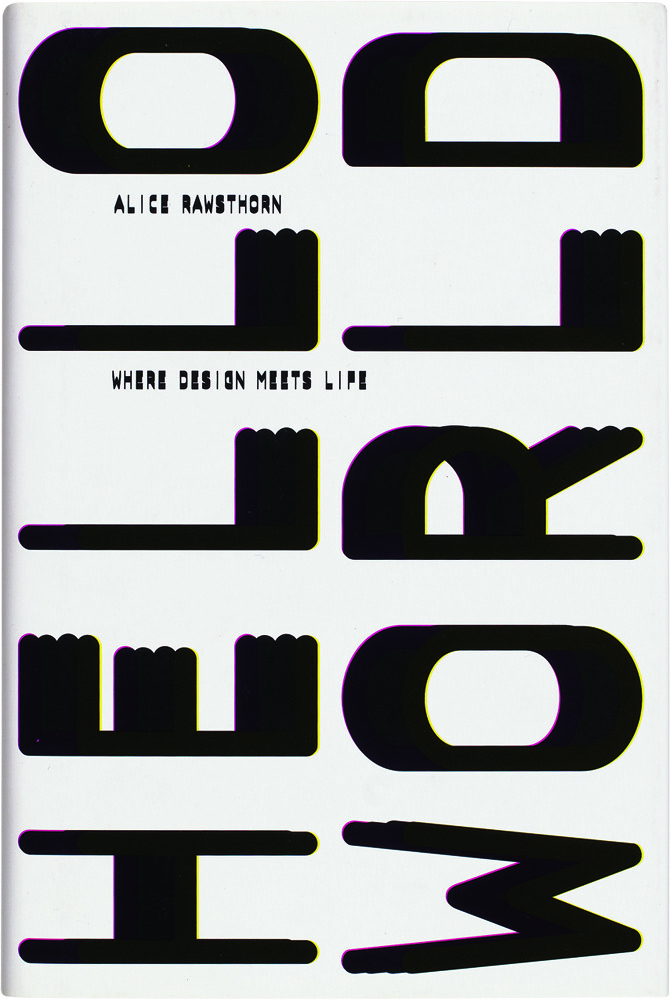

Hello World: Where Design Meets Life

By Alice Rawsthorn<br />Book design: Irma Boom<br />Hamish Hamilton, £20, $30

Books about design aimed at a relatively broad audience that are historically informed and critically acute are few and far between. This is partly because they are so difficult to pull off. Hello World succeeds where others fail because Alice Rawsthorn manages to explain how design touches all aspects of life – from things we readily think of when we hear the word design, like a chair by a signature designer, to things that we tend to relegate to the periphery of design, such as an anonymously designed world cup football.

In this sense, Rawsthorn’s opening gambit in the prologue of Hello World is telling: ‘Try to imagine that you have never seen a smartphone before … Would you expect something slimmer than a cigarette case and not much taller or wider to be stronger than a bulldozer? It is a remarkable achievement, which demanded courage, vision, knowledge and skill from the scientists involved, but their work may never have left the laboratory and transformed the lives of millions of people, if not for design.’

As with this passage, throughout Hello World the language is precise without being reductive, and the examples chosen are judicious. Rawsthorn has managed to transpose the crisp prose style developed in her weekly column for the International Herald Tribune into a format that allows for sustained passages of analysis and a greater historical sweep. In this, her writing reminds the reader of Reyner Banham’s – unapologetically Pop, but with a critical underbelly. By titling the first chapter of Hello World ‘What is Design?’ and the second ‘What is a Designer?’, Hello World follows in the footsteps of a number of important books on design, including Bruno Munari’s Design as Art and Norman Potter’s What is a Designer: Things, Places, Messages. The reason for this insistence in starting from basics, it seems, is down to each writer’s rejection of commonly held assumptions about what defines design and the designer. By fashioning their own definitions anew, each author says something about the roles of design and the designer in the epochs in which they make their main contributions: Munari in the 1930s to the 1950s, Potter in the 1960s to the 1990s, and Rawsthorn from the early 2000s (during her stewardship of London’s Design Museum) and in her writing today.

A key element Rawsthorn uses to engage her reader and propel them through the thirteen chapters of Hello World is narrative. Each chapter opens with a poignant tale, embedded in which is the nucleus of the themes the chapter will deal with. For example, the first chapter opens with a fable about China’s first emperor Ying Sheng in 246 BC and the way he used ‘design thinking’ to overcome his adversaries both on and off the battlefield and then effectively communicate the results to his subjects. The chapter then weaves in Barack Obama’s recent presidential campaigns and the palaces of Louis XIV among many other examples. The second chapter begins with a story about Blackbeard the pirate and the visual communication strategies he developed – such as the skull-and-crossbones flag to signify terror. Rawsthorn then proceeds to analyse case studies as various as Peter Saville’s involvement with the identity of Manchester and Wedgewood ceramics. The chapters come and go at a clip but the narrative opener remains constant.

The reader of Hello World cannot also help but be engaged by the fusillade of tart judgements in each chapter. Two of the best are reserved for Philippe Starck and the Wolff Olins Olympic logo: where Rawsthorn describes Starck as ‘a burly, mal barbu figure who bears a distinct resemblance to Desperate Dan, the pie-scoffing hero of a cartoon strip,’ and of the Olympic logo, which was designed to be easily recognisable in multiple applications, Rawsthorn quips: ‘admirable though versatility is, what is the point if the logo is equally dire in every incarnation?’

In the near seven-year period Rawsthorn’s column has been running in the International Herald Tribune, she has developed one of the most important platforms for design in the international mainstream media – her role at the World Economic Forum in Davos is testament to this. But the museum-goers who ceased visiting London’s Design Museum in 2006 when Rawsthorn left – and they are legion – wish she would also occasionally step off the page and into the museum again.

Alex Coles, critic, editor of EP journal, London

First published in Eye no. 86 vol. 22 2013

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 86 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.