Spring 1995

Should you be on the internet?

The internet: Looking past the hype

‘Surf the information superhighway’, ‘Communicate with 20 million users around the world’, ‘Access any data, anytime, any place’. If you didn’t come across at least one of these phrases in the last year you were probably on another planet. The continued combination of the words ‘information’ and ‘highway’ has excited a lot of people but informed few; without some clarification, many will conclude that the internet is the Emperor’s new highway.

There are a number of good – and some urgent – reasons for designers to begin to use the internet, but few of them have been realistically discussed. The internet has been the focus of attention for a number of other reasons: it is not privately controlled and has open standards, making it a model for global network; resources available on the network – software, information – are ‘free’ (primarily because there is no structure in place for cash transactions); connection to the network has been simplified with the standardisation of the basic software required for Macintosh and PC and the appearance of a number of companies providing dial-up connections via modem; and lastly, large amounts of information have become accessible via a graphical hypertext-based interface – known as the World-Wide Web – where even novices can format pages.

Ironically, the lack of charging structure is one reason why the internet will not reach critical mass in the near future: most things worth having on-line – publications, news wires, stock market prices – have a cost overhead that can only be met by direct payment from the consumer. A second reason is that, despite all the improvements in software and hardware, the internet is still not as easy to use as other technology in wide circulation, such as the television or VCR.

The internet is not the whole story of on-line communication between computers. For many years there have been private services allowing subscribers to connect to extensive networks from their computer via the telephone system. Some, such as CompuServe, have a global reach. In the US, America On-Line has the fastest growth rate, while Prodigy (owned by Sears and IBM) has the largest subscriber base. Apple Computer has recently launched eWorld – the requisite software is bundled with new Macintosh computers – while PC users who upgrade to the Windows95 operating system will have built-in access to the forthcoming Microsoft Network. Delphi, until recently the smallest of the big fish in the US, was purchased last year by News Corporation which will probably use it as a vehicle for publishing its own and other publishers’ titles on-line. Services like these provide content within controlled networks and can charge for access having first established a billing arrangement with their users. But it is for this very reason that they do not represent the future of the on-line world: as the last 15 years in the computer industry have shown, users do not want to be straitjacketed by closed systems, and producers want the kind of shrink-wrapped, standard tools that have grown up around the internet.

What are the benefits for designers using the internet? The first is electronic mail, which is largely analogous to traditional poste restante mail. A message is composed, addressed and mailed – perhaps with attached files. It is then stored in the recipient’s ‘mailbox’ on another computer until that person connects to pick up their mail. Messages can be sent at any time to people in different time zones with whom telephone conversation would be difficult – for a uniform (and minimal) cost. Corporate clients are increasingly likely to want some communication with their designers by electronic mail, particularly when it involves exchange of text or even electronic proofs.

The second benefit to be gained from using the internet is access to files – primarily software. The internet allows access to a great deal of ‘shareware’ (software that the creator distributes freely, asking payment only from those who continue to use it), and also to monitor software updates and bug fixes made available by developers. There are few design studios today that do not rely heavily on computers, and the ability to find a solution instantly to a software problem can be not just time saving, but life saving.

The third reason for using the internet is that it – or something like it – is going to have an increasing impact on print. There is a greater emphasis today on design for digital products and interfaces, whether they be multimedia CD-ROMs or World-Wide Web pages on the internet. Many companies and private institutions want to make information available on-line; publishers of magazines and journals are looking at ways to develop commercial products on-line; retailers want to advertise and sell on-line. At present, control over the interface is crude and the technology limited, but that makes now the best time to start learning about the possibilities and pitfalls. On-screen graphics will develop into an area of dynamism and excitement for designers.

Another reason for using the internet is to have discussions with other designers. ‘Newsgroups’ are discussions in which a posting by one user on a particular topic is followed up by replies from other readers of that discussion group. At present there are no graphics newsgroups; many are touted but none yet active – one of the frustrations of a medium that is evolving fitfully.

If you want to use the internet, how do you go about it? First, get an account with an internet provider. You will be charged a flat fee of between £100 and £200 per year, generally with an option of paying in monthly instalments, and given a password and on-line ‘name’ (effectively your electronic mail address). Next you will need a modem (see Eye no. 9 vol. 3) with a minimum speed of 9600bps – your internet provider will be able to recommend or sell one to you. Although most personal computers run either the Macintosh or Windows operating system, the internet was built around a third system known as Unix, which has its own network language called TCP (Transmission Control Protocol). For a Macintosh computer to talk this language it requires the MacTCP control panel; this is not free, but at least it comes with System 7.5 (an upgrade which, apart from the QuickDraw GX element, is recommended). Once you can ‘talk TCP’ you can use the internet, though you still need to establish a connection. A modem connection is usually made via SLIP (Serial Line internet Protocol) on a Windows computer, and via PPP (Point-to-Point Protocol) on a Macintosh. The software for making a PPP-connection is free and is usually supplied by your internet provider, hopefully pre-configured, leaving you simply to enter your password and on-line name.

None of this is as straightforward as users of Macintosh software have come to expect. In the future, however, Apple is likely to incorporate internet access more fully into the Macintosh operating system – making resources on the internet accessible via desktop icons, for example. Developments like this are over a year away, and all discussion has to far been unofficial. Apple has a well-earned reputation for making difficult technologies usable, but often it does so too late to establish its solution as a standard. A lot rides on Apple getting this right on time.

Once you have a connection you can begin to use the network. Most of the software required for electronic mail, file transfer and Web browsing is free or shareware – often developed under the auspices of American colleges – and will probably be supplied by your internet provider. The most popular applications are Eudora for electronic mail, Fetch for file transfer (although Anarchie is commonly used if the location of the file is not known), and Netscape for Web browsing. Some of these programs come in a cut-down free version as well as the fully featured commercial version; decide whether you like them and need the extra features before parting with any cash. One of the best aspects of using internet software is the fact that help, in the form of ‘manuals’, discussions and FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions) documents, is available on-line and always up to date.

The main pitfall with file transfer is the format in which files arrive. Most computers on the internet are Unix-based and know nothing of Macintosh file formats; software stored on them may be in a variety of formats and need decoding at your end. Software such as Fetch often does this automatically, but it is worth finding a copy of Stuffit Expander, which dedicates itself to solving these knotty problems.

Most new internet users find themselves initially addicted, forget that they are paying for a phone call and sometimes even forget that they have commitments in the real world. This reveals the immaturity of the technology. We don’t use the telephone because it is there, and are rarely even aware of it as a technology at all. When we are able to say the same about the internet, then it will have become truly useful.

Currently, the excitement is in developing applications for, and ways of working with, this technology. For designers this means specifically looking at interfaces, but in a new world, where roles have yet to be defined, design may come to mean much more. Where there is little that would be recognised as ‘design’ in the sense that we understand it today, other issues will come to the fore: organisation and quality of information; indicating the nature and extent of content; helping users to find what they want. Designers could again begin to play the role of art editors in the classic sense – a tradition that could be productively renewed as publishing moves into the electronic age.

Nico MacDonald, Eye production consultant, London

First published in Eye no. 16 vol. 4, 1995

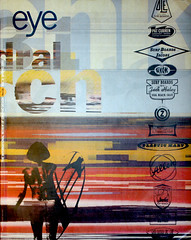

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.