Winter 2014

Still standing and outstanding

Constructing Worlds

Barbican Gallery, London EC2Y 8DS<br> 25 September 2014–11 January 2015<br>

The demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St Louis, Missouri, in the spring of 1972 has been elevated by Charles Jencks and others into one of the creation myths of architectural postmodernism. The sense that a destructive act could bring something new into being simply added a pinch of Dionysiac grist to the postmodernists’ mill. Yet, as we now know, the story didn’t end there. A decade later, in 1982, footage of the exploding buildings was incorporated into Godfrey Reggio, Ron Fricke and Philip Glass’s ecological jeremiad Koyaanisqatsi. Nineteen years after that, another project by Pruitt-Igoe’s architect Minoru Yamazaki, the World Trade Center complex in New York, would in its destruction assume a nimbus of tragic and humane associations that the buildings could never have attracted while still standing.

If the phoenix currently rising from the ashes of Lower Manhattan is a bit of a disappointment, that is a measure of the complex sensitivities, and the still more complex web of interests, involved. But at least 9/11 put an end to the idea of collapsing buildings as spectator sport.

An outstandingly coherent and visually exciting exhibition of architectural photographs at the Barbican rejects postmodernist critique – though it does feature a few postmodernist buildings – in favour of what might be called the ‘humanist’ line, locating architectural form within a complex continuum of decay and renewal and untidy day-to-day use.

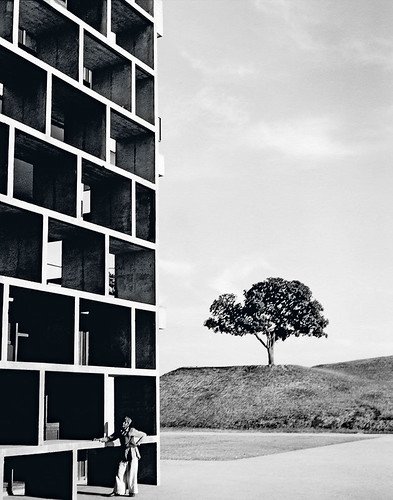

There is a ‘pure’, depopulated formalism, or a dehumanising primitivism, in several pictures (sometimes both at once, as in Lucien Hervé’s velvety-black images of Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh, through which the occasional grimacing local can be seen). There is inevitably a strong sense of the tragic here and there, whether from a Koyaanisqatsi-style eco-perspective or the standard failed-utopia one. Yet as a whole it is a show that finds variety, and does not shy away from ambiguity, in what might be thought a fairly monolithic theme.

A strong narrative line is rigorously enforced by the gallery staff, who ensure that the visitor starts with Berenice Abbott’s jaunty and eventful pictures of a New York in transition, then moves in an orderly fashion through Walker Evans, Julius Shulman’s Mad Men-esque images of Case Study Houses, Hervé, Ed Ruscha’s aerial views and a wall of Bernd and Hilla Becher water towers. The central zone of the lower floor is divided into large booths of a suitably strict formal purity displaying more recent practitioners, including Andreas Gursky’s artfully sutured composite picture of crowds at Sé metro station in São Paulo, Guy Tillim’s images of avenue Patrice Lumumba in Léopoldville, Luigi Ghirri’s studies of works by Aldo Rossi (cleverly installed in a very Rossian cylinder) and Hélène Binet’s of Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum in Berlin (which make the building appear rather gimmickier than one hopes it is in reality).

The consistency of the images past which you’re processed mean there’s inevitably some repetition. A chapel by Walker Evans resembles a later one, in colour and set at an angle, by Stephen Shore. There’s a lot of iron, glass and concrete (and, later, a lot of decaying concrete). But even if you are familiar with most of the images – and if you’re interested in either photography or architecture, chances are you will be – the juxtapositions are informative. The Shulman pictures are generally held up as exemplars of a postwar ‘aspirational’ Modernism, alongside hi-fi systems or Clement Greenberg articles; but in this company they seem much more concerned with the thrifty, prefabricated structure of the houses. A trellis of cast iron at Rossi’s Modena cemetery casts you back to Abbott’s images of the Manhattan skyline.

The last two displays, as you head to an exquisitely curated gift shop and the exit beyond, assert the transcendence of nature, in Nadav Kander’s views of the Yangtze, and of humanity, in Iwan Baan’s pleasingly messy images documenting life in the carcass of Torre David, a financial megastructure in Caracas, abandoned unfinished after an economic crash and subsequently squatted. This failed utopia is made to look rather more attractive than many of the other kind, as settlers personalise their little corner or tier of the vast shell, then apply themselves to everyday tasks: selling groceries, pumping iron or cutting hair, and living ordinary, disorderly lives.

Photograph by Lucien Hervé of the High Court of Justice in Chandigarh, 1955: ‘“pure”, depopulated formalism’.

Top: Water towers photographed by Bernd and Hilla Becher, in the Barbican’s exhibition ‘Constructing Worlds’.

Keith Miller, writer, London

First published in Eye no. 89 vol. 23 2014

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 89 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.