Summer 1992

The keyboards that ate the world

Designers on Mac

Diane Burns and Takenobu Igarashi, Graphic-sha, £60The celebratory aspect of this publishing exercise is evident from the outset. The art director, Takenobu Igarashi (credit with instigating the project), and the author, Diane Burns, unselfconsciously revel in their Macintosh-based method of working, and extol the trouble-free production process that spanned continental divides. After encountering a flow diagram that is meant to demystify the way the book was written, designed and printed, but reads more like a shopping list of state of the art hardware – the smartmoderns, scanners, bernoullis and supermacs without which none of this would have been possible – the reader could be forgiven for expecting the book to contain little more than a flow of similar endorsements.

The authoring team obviously believes the hype, and a cynical reading could find fault with the fact that all other computer systems receive unmitigated bad press, and are cited as “dedicated”, inflexible and lumbering. Though the initial premise may have been to praise a common tool in some of the most innovative studios around the world, through the words of the interviewees, reprinted almost verbatim, what becomes obvious is the resolution of designers to defy the threat of homogeneity the Macintosh poses.

Each chapter features an interview with a big-name designer. All are asked the same questions: “How, when and where did you first encounter a Mac?”, “How is the Mac used in your office?” and “How should design students be introduced to the Mac?”, illustrated with examples of work showing progression from Mac-novice to Mac-guru. The reader is treated to a through-the-keyhole encounter with the “personalities”, thanks in part to some candid portraiture and views of the designers in their natural habitat (the design studio). But the most revealing section of each chapter shows the step by step stages of a Macintosh-run project, with information on the soft and hardware used, how images are sourced, manipulated, combined and printed: in short, the nuts and bolts of the design process. The final section of each chapter shows a portfolio of the design studio’s work, which could be subtitled “their greatest Mac-achievements”.

Designers on Mac demonstrates that even though the same tools are used by people skilled in the same techniques, their output is not simply a result of the common technology, but of the different cultural and economic backgrounds against which they work. The three Japanese writers, Susumu Endo, Kazuo Kawasaki and Yukimasa Okumura, work across a range of disciplines from printmaking to product design to mass-circulation graphic design. Their work shares elements from traditional Japanese visual languages combined with commercial values. April Greiman, working in California between Silicon Valley and Hollywood, is fascinated with “hybrid” imagery and the very latest technology. Erik Spiekermann cites his “Germanic mind” as responsible for his love of order and ability to design timetables. Mariscal likes the excess of the Macintosh: “with the computer you have 3000 different ways”. So instead of simply extolling the virtues of computer technology, the book points to more profound truths about the varied components of design and the nature of creativity.

All the designers agree that the Macintosh has changed their way of working, making life easier on the one hand, but also creating new problems. The two main questions asked of the, about how they use computers and how design students should be trained, reveal the Macintosh’s basic drawbacks. Whether their studios house rows of self-motivated Mac-literate designers (Spiekermann), or whether the designer collaborates with several Mac-based designers simultaneously (Greiman), or has a personal Mac-collaborator (Endo), they all agree that the technology is flexible, but still very primitive; pushing the technology to its limits can result in irreparable losses. For example, inaccurate colour matches between monitor, printout and printing press can undermine one of the major advantages of the system: quick, easy colour experimentation.

Spiekermann foregrounds the most negative aspect of the technology for graphic design personnel. Because the time-saving aspect has been jumped on by clients and turned into a money-saving necessity, designers have become typesetters, but lack their specialised knowledge. Quality is gradually eroded, mistakes are missed, and everyone is overworked. “So we are stuck with the responsibility, and that’s one thing I don’t like about this Macintosh business.” The attendant fear is that this downgrading of the designer’s status could begin at college, if the basic design skills of observing, drawing and making are neglected by students eager to become computer-literate, and encouraged by tutors who want to produce employable graduates. When they enter the world of work, they will be able to compute, but will they be visually illiterate?

The impact of the Macintosh technology on the design world is profound. But this book only scrapes the surface.

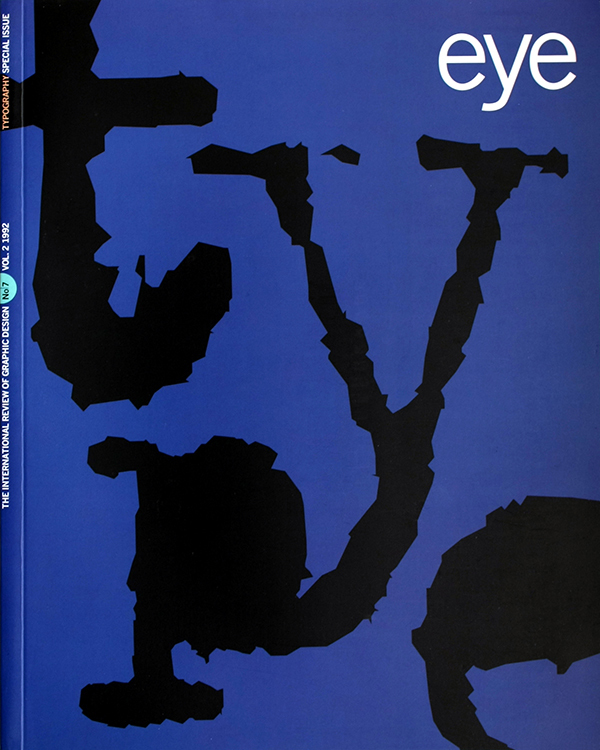

First published in Eye no. 7 vol. 2, 1992

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.