Autumn 2008

Revelations in style

Gallimard’s Découvertes series secures readers’ loyalty by showing respect for their curiosity and intelligence. Critique by Rick Poynor

In the early days of Eye, we ran an article about the New Horizons series of illustrated introductions to the arts, culture and science published by Thames & Hudson. Our writer considered them as an example of how book publishers threatened by supposedly more appealing media – television, video, computer games and CD-roms (remember them?) – were having to rethink their old-fashioned, bookish conventions. ‘This means looking afresh at the ways people read,’ wrote Jim Davies, ‘ditching centuries-old assumptions, and recognising that the . . . traditional, linear approach to the presentation of information is anathema to emerging generations . . .’

This was written (in Eye no. 13 vol. 4, Summer 1994) before most people had access to the internet. We have heard the same essential argument repeated many times since then, but New Horizons must have been doing something right because the series is still going fourteen years later and 84 volumes are currently in print. This is nothing, though, compared to the French publisher Gallimard’s Découvertes (Discoveries) series, from which New Horizons draws its titles. Découvertes, which began in the late 1980s, now boasts a list of more than 500 volumes. By any standards, this ambitious, encyclopedic undertaking is one of the great projects of contemporary popular publishing.

Although I have bought a number of the New Horizons over years, they seem more routine compared to the original versions of the same books. No doubt it is for sound commercial reasons, but the British series feels too selective, too market-conscious, less inquiring, discursive or speculative, less . . . well, French. Even the lack of numbering on the New Horizons titles suggests a different attitude. Gallimard’s spine numbers signal a commitment to all the Découvertes it has ever published. I saw them shelved in numerical order, with a few gaps, in a French bookshop this summer. Without the numbers, books can be quietly dropped – a New Horizons from 2006 lists fifteen or more titles that are no longer available.

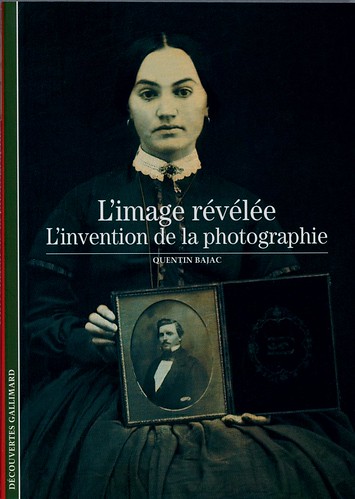

Thames & Hudson tends to go for the more obvious subjects and it makes the titles more descriptive and banal. So L’image révélée: L’invention de la photographie becomes The Invention of Photography. What happened to the idea of revelation? Since the French cover picture of a woman showing a photograph of her husband – an image both intimate and sociological – no longer worked so well with the title, T&H changed it to something more arbitrary, a Pierrot with a camera. Although it is essentially the same book, it has ended up feeling less sophisticated and sure of itself than the French version, a casualty of the unfocused, ‘something for every reader’ approach.

Below: L'image révélée by Quentin Bajac, first published 2001.

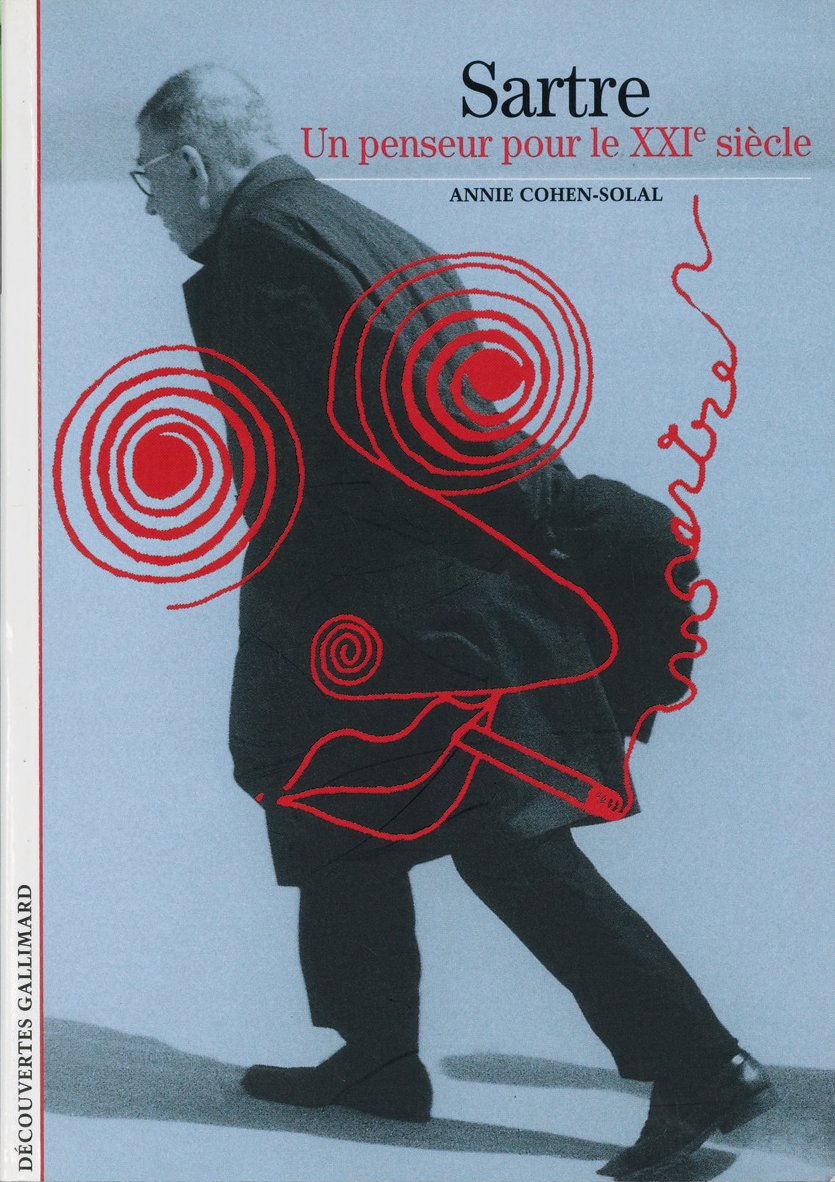

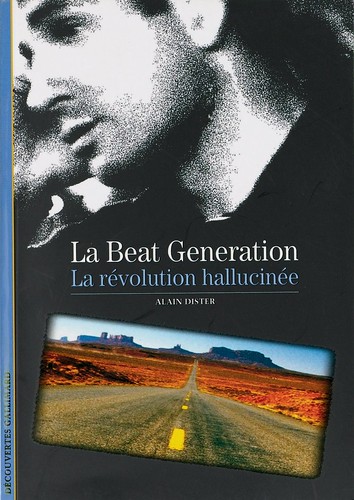

Top: Sartre by Annie Cohen-Sohal, first published 2005.

Many of the more intriguing French titles never make it into English. This includes Découvertes’ entire literature series, so don’t go looking for New Horizons about French writers such as Balzac, Baudelaire, Camus and Sartre, or for that matter, about the Beat Generation (subtitle: La révolution hallucinée – beautiful). The Littératures have some of the best covers of all, based on author photographs paired with a piece of the author’s handwriting or, even better, with a line drawing, often stylised and witty. The French editors show a wonderful confidence in the cultural tastes and intellectual appetites of readers out to buy compact, low-cost, illustrated guides. So we have – though not so far available in English – books about melancholia, in the arts series; the adventure of mysticism, in the religion series (another great title: Seul avec Dieu – Alone with God); and fear of wolves (La peur du loup), in the culture and society series. Découvertes has twenty books about cinema, covering everything from Feuillade to Godard; New Horizons shuns the big screen.

While the internal structure and style of the books is durable enough to have remained unchanged for two decades, Gallimard has made some minor adjustments to the typography along the way, notably the use of bold sans serif subheadings in place of the underlined serif the publisher once favoured. It makes sense that the contents page is now at the front rather than lost at the back, as it was for years. Most strikingly, the newer covers are matt-laminated rather than glossy, giving the cleverly chosen cover images greater allure, and earlier volumes are being reprinted to match. The elegant cover typography has the same feeling of quality and the series’ visual identity is stronger than ever.

Gallimard’s British partner could learn a lesson here: such panache encourages loyalty. By respecting the reader’s intelligence and going beyond the obvious ‘educational’ subjects presented in a predictable way, Gallimard makes you curious to see where this editorially innovative and consistently adventurous series will go next.

La Beat Generation by Alain Dister, first published 1997.

Rick Poynor, writer, founder of Eye, London

First published in Eye no. 69 vol. 18 2008

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.