Thursday, 11:10pm

18 February 2010

20-20 digital hindsight.

Early adopters of computer art and design enter the V&A collections

In the past few years the Victoria and Albert Museum has amassed what is now the national collection of computer-generated art and design, writes V&A curator Honor Beddard.

Many people are surprised to learn that the collection begins as early as 1952. The Word and Image Department at the Museum has been acquiring digital art since the 1960s, but the core of its collection is formed of two recent donations; the archive of the Computer Arts Society, London, and the collection of Patric Prince, an American art historian.

Above: Ben Laposky, Oscillon 40, 1952, C-type photographic print. Given by the American Friends of the V&A through the generosity of Patric Prince. © Sanford Museum, Cherokee, Iowa, US. Photo: V&A Images.

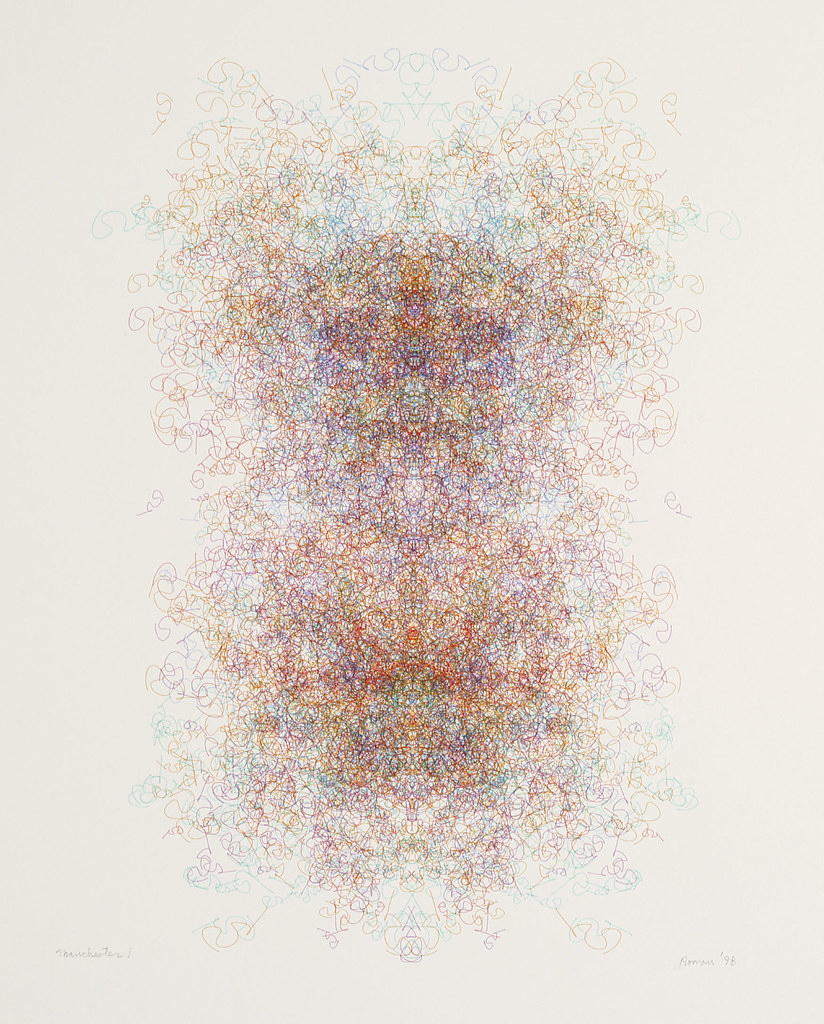

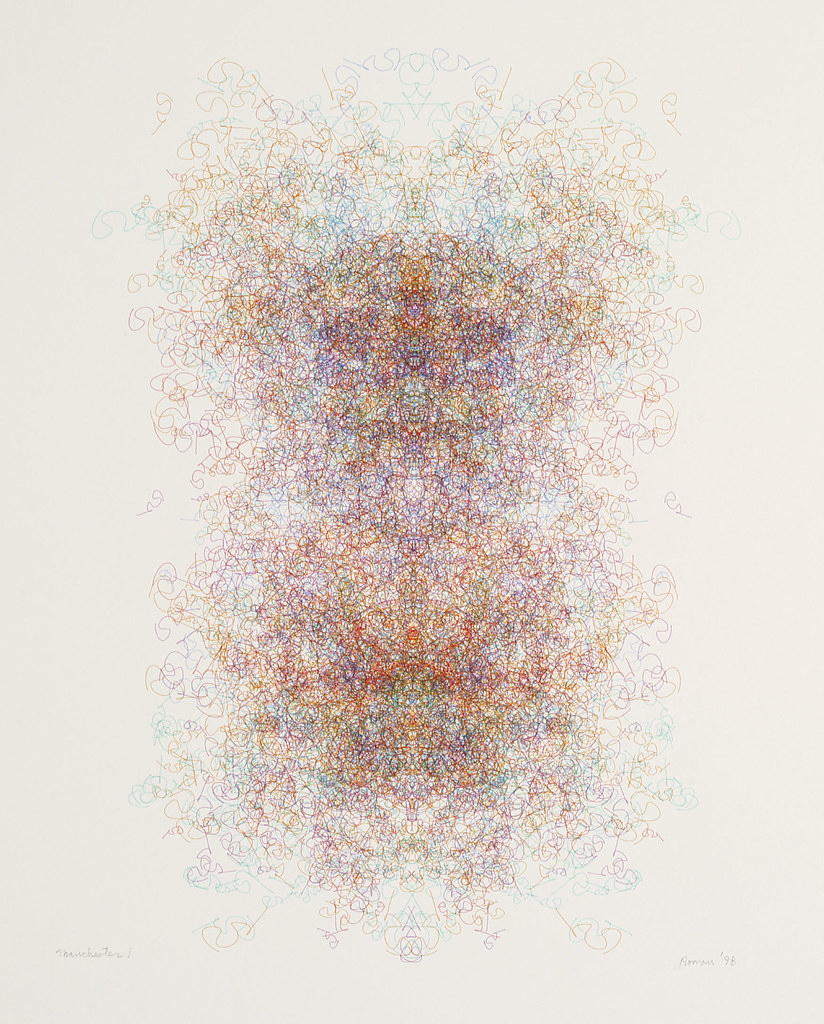

Top: Roman Verostko, Manchester Illuminated Universal Turing Machine #1, 1998, detail (see below).

Some of the earliest works in the V&A’s collection were created using analogue computers and machinery, which were manipulated to exploit their graphic capabilities in a way that anticipated the digital work that was to follow. Early digital practitioners began working in the mid to late 1960s and set themselves the difficult task of generating images using algorithms, or code, that they had written themselves. Their computers offered no user interface or screen and drawings could not be seen until they were printed.

Below: Frieder Nake, Hommage à Paul Klee 13/9/65 No. 2, 1965, screenprint after a computer-generated drawing. Given by the American Friends of the V&A through the generosity of Patric Prince. © artist. Photo: V&A Images.

The result was hard-edged, linear geometric works of art whose formalist approach was in keeping with the Modernist culture from which they sprang. By the 1970s artists with traditional fine art training were beginning to adopt the computer into their practice. Many, such as Manfred Mohr and Vera Molnar, were already working in a systematic way that prefigured their use of this new technology. By the 1980s personal computers were becoming increasingly common and the arrival of off-the shelf-software radically changed the nature of computer-generated art and design.

Below: Herbert W. Franke, Quadrate (Squares), 1969-70, screenprint after a plotter drawing. Given by the Computer Arts Society, supported by System Simulation Ltd, London. © the artist. Photo: V&A Images.

The collection at the V&A reflects all these developments and more. It holds plotter drawings from the 1960s until the present day, early impact prints and a variety of more traditional prints, such as screenprints, etchings and lithographs, in which the computer played a key role in the design or production.

Above: Manfred Mohr, P-021, 1970, screenprint after a plotter drawing, from the portfolio ‘Scratch Code: 1970-1975’, edition 51/80, published by Editions Média, 1976. Given by the American Friends of the V&A through the generosity of Patric Prince. © the artist. Photo: V&A Images.

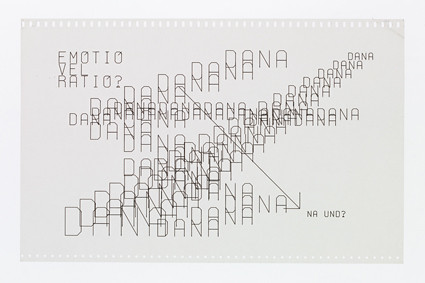

Below: Unknown, ca. 1970s, plotter drawing on computer paper. Given by the Computer Arts Society, supported by System Simulation Ltd, London. Photo: V&A Images.

The Museum also holds early laser prints, inkjet prints, negatives from computer animations, a range of photographic prints, and even some stills from early video games. Our holdings are not yet fully comprehensive but the V&A continues to acquire works as recognition of this relatively under-explored area of art and design grows.

Below: Roman Verostko, Manchester Illuminated Universal Turing Machine #1, 1998, multi-pen plotter drawing with gold leaf. Given anonymously. © the artist. Photo: V&A Images.

The collection has brought with it some challenges, both in terms of recording and in conserving, but it offers the benefit of hindsight that is a major advantage as the Museum begins to acquire contemporary digital art and design. The V&A is the first UK museum, and one of only a handful world-wide, to collect this type of material, a status that was recognised in the recent awarding of an Arts and Humanities Research Council grant that has allowed us to research the collection further.

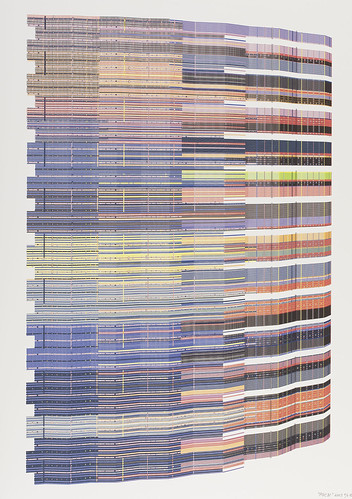

Above: Mark Wilson, p9303, 2007, digital inkjet print on paper (1/5).

Below: Mark Wilson, PSC31, 2003, digital inkjet print on paper, edition 5/5. Given by the artist. © the artist. Photos: V&A Images.

A current display at the V&A, ‘Digital Pioneers’ (until 25 April 2010), contains highlights from the collection and provides a historical counterpart to the contemporary V&A exhibition ‘Decode: Digital Design Sensations’ (see ‘Electric Narcissus and digital Echo’).

Article by Honor Beddard, Curator, Word and Image Department, V&A.

See also the ‘Computer art’ feature on the V&A website.

Eye, the international review of graphic design, is a quarterly journal you can read like a magazine and collect like a book. It’s available from all good design bookshops and at the online Eye shop, where you can order subscriptions, single issues and classic collections of themed back issues. Eye 74 features a Reputations interview with Karsten Schmidt, whose work is featured in ‘Decode’ and in its promotional posters and animations.