Friday, 10:30am

26 August 2011

Brothers in arts

The Stenberg brothers’ posters are as beguiling today as they ever were

While debates rage about the relevance of the poster to contemporary graphic design (see ‘Help!’ and ‘Olympic deliverance’ on the Eye blog), writes Alexander Ecob, one is irresistibly drawn to work from a time when posters were vital.

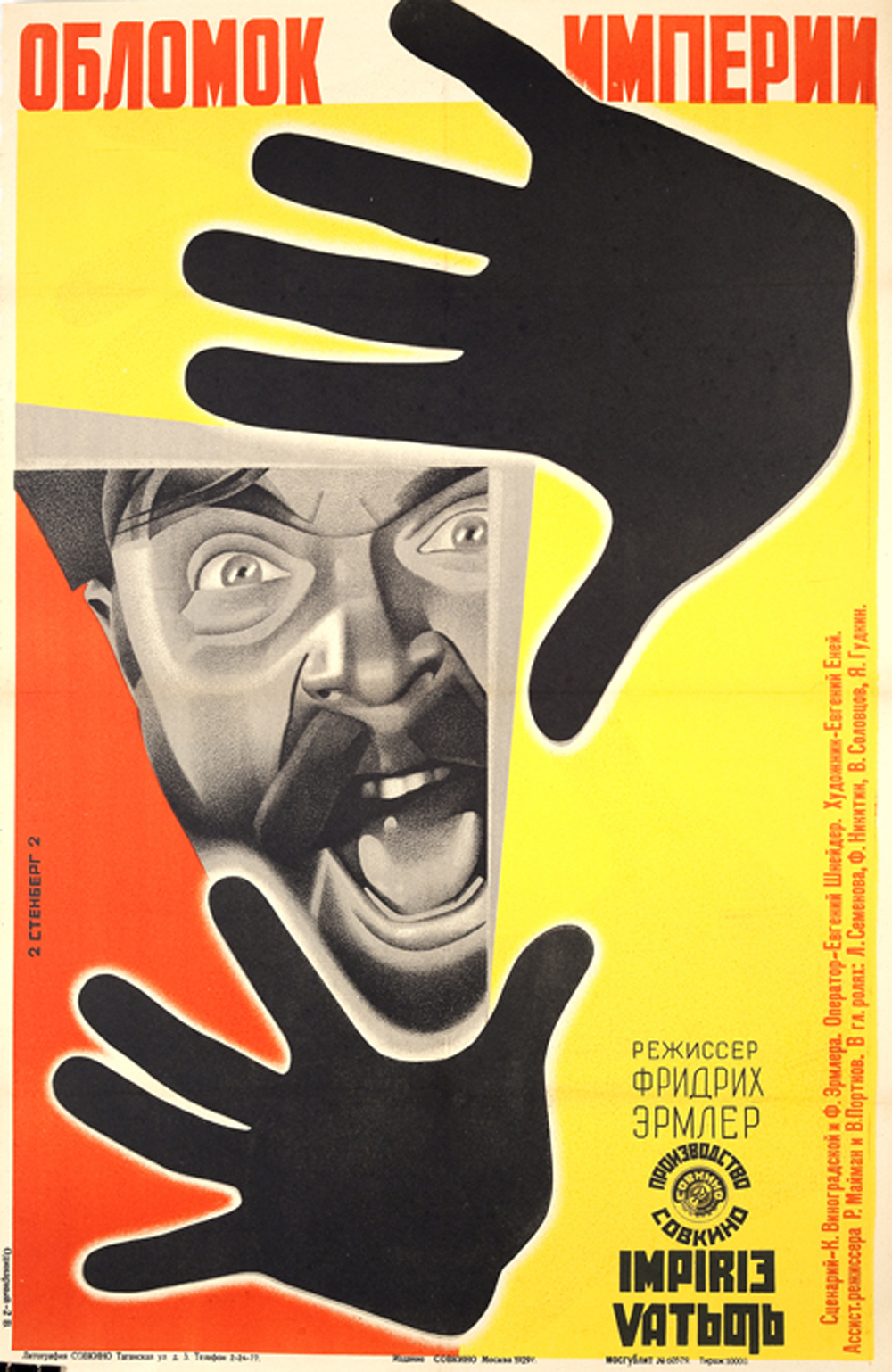

Top: Georgii & Vladimir Stenberg, A Fragment of an Empire (1929). Courtesy Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York.

Above: Georgii & Vladimir Stenberg, Mospolygraph Pencil (1928). Courtesy Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York.

To many, the early days of the Soviet Union are seen as a golden age of poster design. Fuelled by a combination of exploding idealistic and artistic movements in post-revolutionary Russia and the emergence of practitioners such as Aleksandr Rodchenko, all backed by a new Bolshevik government strongly supportive of design, it is plain to see why.

Eager to disseminate their messages and ideologies to the wider population – 60 per cent of whom were illiterate at the formation of the Soviet Union – the Bolshevik party was supportive of the cinema industry, not only in production of propaganda, but as a whole.

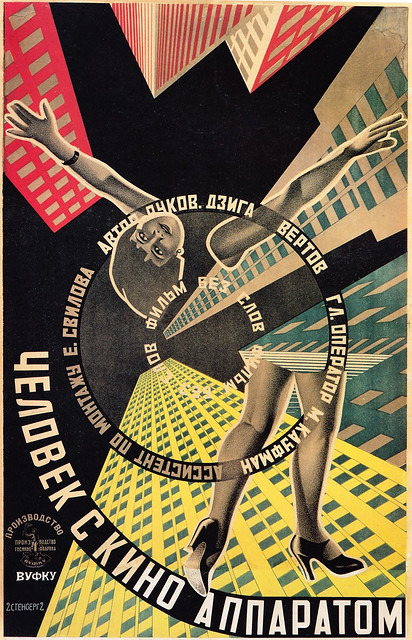

Above: Georgii & Vladimir Stenberg, The Man with the Movie Camera (1929).

While Rodchenko and Kandinsky immediately spring to mind when considering artwork from this period, an important portion of the output came in the form of cinema posters created by the prolific Vladimir and Georgii Stenberg, who were relatively forgotten until a major retrospective at the MoMA in 1997. The brothers created more than 300 cinema posters in the decade before Georgii’s death in 1933.

Born in 1899 and 1900 respectively, Vladimir and Georgii both studied engineering and fine arts at Stroganoff School of Applied Art. They began working as sculptors, architects and designed railway carriages and theatre sets, among other things, before going on to design hundreds of cinema posters for films, from documentaries to Buster Keaton comedies. Some suggest that a key to their graphic success was their deep-rooted knowledge of the theories and methods of theatre and film-making.

Above: Georgii & Vladimir Stenberg, A Shrewd Move (1927). Courtesy Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York.

The brothers, who always worked in collaboration, were prominent members of Moscow’s avant-garde – held in high regard for their stylistic representation of films’ subject matter and with their photo-realistic rendering. While many of the pieces have the look of Dadaist photomontage, nearly all of their posters were illustrated. Technological limitations of the time meant that collaged images could not be reproduced to a high standard, so the brothers developed a prototype overhead projector, allowing them to project and distort images, portraits and film stills on to their posters which they then illustrated by hand.

Above: Georgii & Vladimir Stenberg, Symphony of a Large City (1928). Courtesy Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York.

Above: Georgii & Vladimir Stenberg, In the Spring (1929).

Although these Constructivist gems were produced en masse, few copies remain, and a number of the works featured in the Tony Shafrazi gallery’s recent Revolutionary Film Posters had never before been exhibited.

The geometric forms, distorted perspective, creative cropping and montaging of different elements and kinetic typography displayed in these posters remain a vital source of inspiration.

Above: Georgii & Vladimir Stenberg, Catastrophe (1926). Courtesy Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York.

Revolutionary Film Posters: Aesthetic Experiments of Russian Constructivism, 1920-33, a comprehensive collection of rare and exquisite Russian film posters, was on view at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York last month.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It’s available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop. For a taste of the new issue, see Eye before you buy on Issuu. Eye 80, Summer 2011, is out now.