Tuesday, 11:10pm

31 August 2010

Escaping Modernism

Edward Weston’s flight from photographic theory

The early twentieth century saw photography dominated by the influence of painting, with the then popular pictorial style drawing its reference points from the impressionist artists of the period, writes Wayne Ford. It was in this style, like many of his generation, that the great photographer Edward Weston (1886-1958) began to work.

Yet a photograph taken shortly before his arrival in New York in 1922 exhibited none of the pictorial blur of his earlier work. In a series of photographs of the Armco Steel plant in Ohio, we see Weston take a straight Modernist approach to his photography. ‘Within days he had set off on a new artistic course that paralleled the Modernist movement that had taken over the art world,’ says Giles Huxley-Parlour, director of photographs at Chris Beetles Gallery where 37 of Weston’s photographs, posthumously printed by his son Cole, are to be exhibited next week.

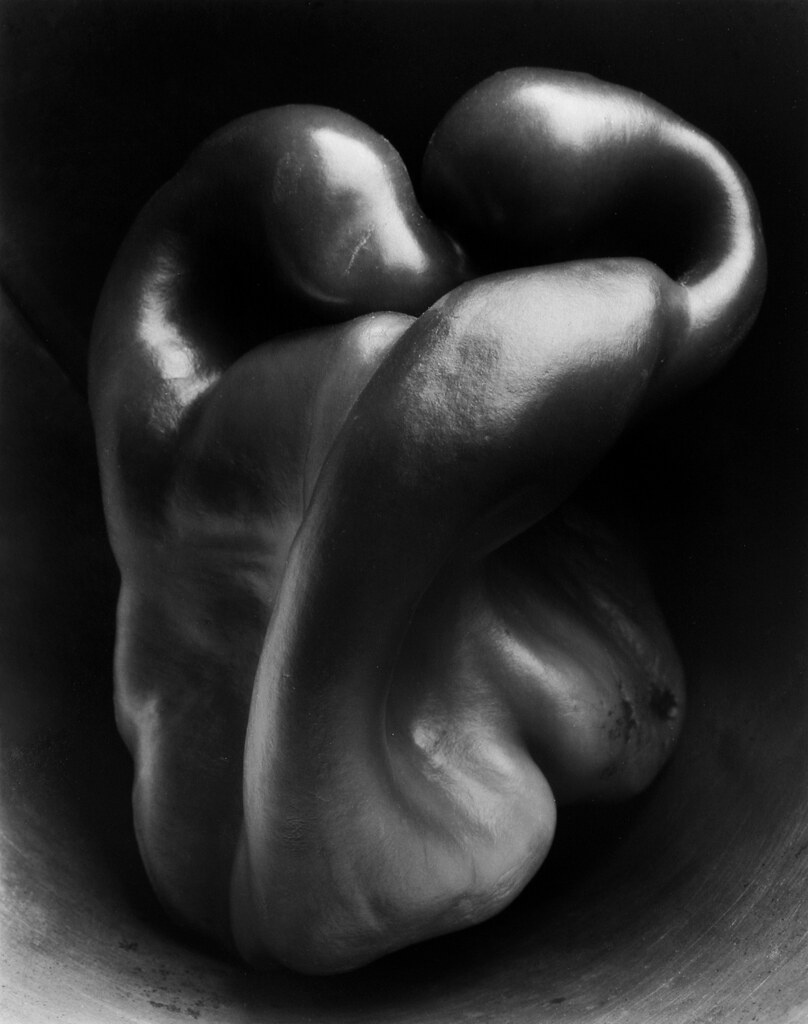

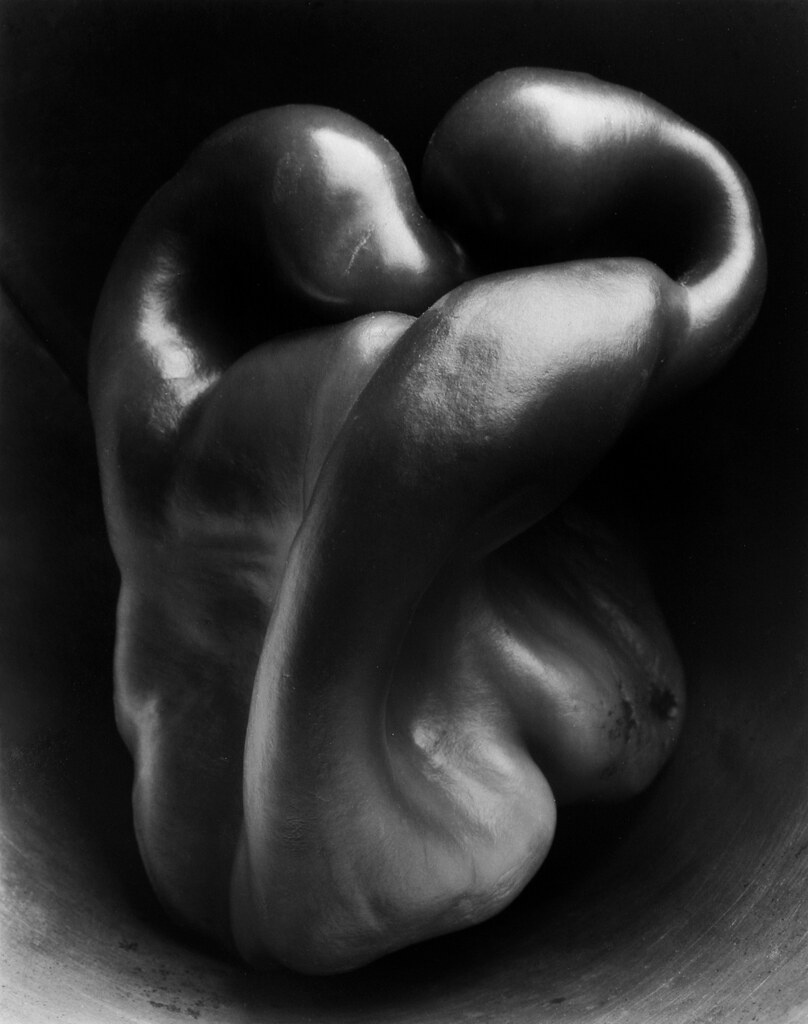

Top: Pepper. Photograph by Edward Weston (1930).

©1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents.

Above: Oceano, Photograph by Edward Weston (1936).

©1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents.

Instrumental in bringing photography out of the soft-focus Victorian era, Weston embraced the Modernist spirit. But to categorise Weston as a Modernist would be incorrect – he was too individual an artist and too anti-theoretical to align himself with any particular movement.

‘He used Modernism to help him towards his own personal photographic aims, beyond which he disregarded it,’ says Huxley-Parlour. In 1930, Weston held his first solo show in New York at the Delphi Studios, the first print to sell, Eggs and Slicer, 1930, angered Weston: ‘I suppose it is purchased because it is “Modern”. I am so sick of the word!’ he exclaimed. ‘One’s spirit of approach may be contemporary, but subject matter is immaterial,’ he continued, reflecting his disinterest in the core element of Modernism: ‘the subject of the modern age.’

Above: Cabbage Leaf. Photograph by Edward Weston (1931).

©1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents.

In 1923, Weston suddenly left his wife and children for a new life and lover in Mexico, a cycle that was to be repeated and which would see him continually move around the West Coast of America, with a succession of different women, and with each move he sought out a place away from the pressures and influences of modern day America. As Huxley-Parlour points out, ‘Weston wanted his art to be his own and, whilst he did inevitably feed off the ideas of others, he tried to reduce this as much as possible. The escape to the countryside provided Nature as the great stimulus, and in turn provided him with another escape — from ideas and theories.’ Weston himself said: ‘let the photographers who are taking new or different paths beware of the very theories through which they advance, lest they accept them as final.’

While living in Mexico with his lover Tina Modotti – a revolutionary and talented photographer whom Weston photographed frequently – he made a photograph titled ‘Excusado’. He wrote: ‘Form follows function. Who wrote this I don’t know, but the writer spoke well! I have been photographing our toilet, that glossy enamelled receptacle of extraordinary beauty … My excitement was absolute aesthetic response to form.’

‘Part of Weston’s mysticism was an interest in, and concerted effort to provoke, responses,’ says Huxley-Parlour, ‘to bring about the intangible power that photography can have on its viewers.’

8 > 25 September 2010

Edward Weston

Chris Beetles Gallery

8 & 10 Ryder Street,

London

SW1Y 6QB

www.chrisbeetles.com

Eye magazine is available from all good design bookshops and at the online Eye shop, where you can order subscriptions, single issues and back issues. The summer issue, 76, out now, is a music special – full contents here, and you can see a selection of visual details on Eye Before You Buy on Issuu. Student subscriptions are half price, see bit.ly/EyeStudentOffer.