Friday, 7:00am

16 December 2016

Eye of Bamako

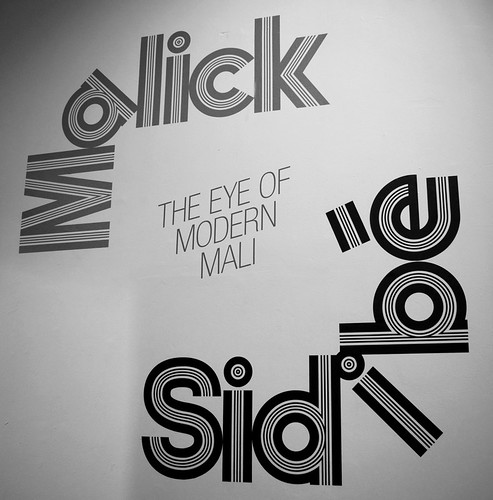

Malick Sidibé: The Eye of Modern Mali

Somerset House, London, until 15 January 2017<br>Malick Sidibé’s photography captured the energy, joy and hope of post-colonial Mali. Review by Mariam Dembele

Malian photographer Malick Sidibé was known as the ‘Eye of Bamako’, writes Mariam Dembele.

Sidibé earned this nickname for his work photographing Mali’s capital city in the years after the West African nation gained independence from France. He photographed the Malian events – weddings, graduation celebrations, beach parties and nights out – in the way his mentor, French photographer Gérard Guillat-Guignard, had covered colonial events in the years before the country’s 1960 independence. The current exhibition, ‘The Eye of Modern Mali’ at London’s Somerset House, includes 45 of Sidibé’s black-and-white prints, which give a glimpse into his world and into the vibrant youth culture of Mali in the 1960s and 70s.

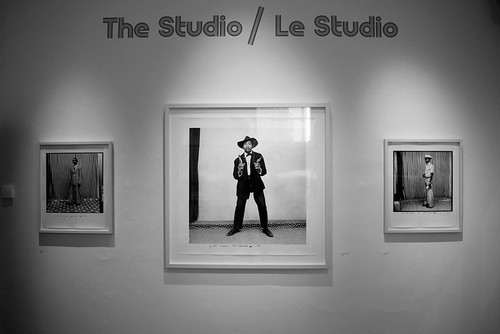

The exhibition is divided into three rooms based on three themes within Sidibé’s work: Tiep à Bamako, Au Fleuve Niger and Le Studio, which translate to Nightlife in Bamako, Beside the Niger River and The Studio. DJ Rita Ray’s playlist of rock’n’roll, pop and Malian roots music plays in the background, giving the visitor an impression of what it would be like to be out for a night at Bamako’s club Las Vegas or sitting in on a photo session at Studio Malick.

The exhibition begins with the theme Tiep à Bamako / Nightlife in Bamako, taken between 1963 and 1965.

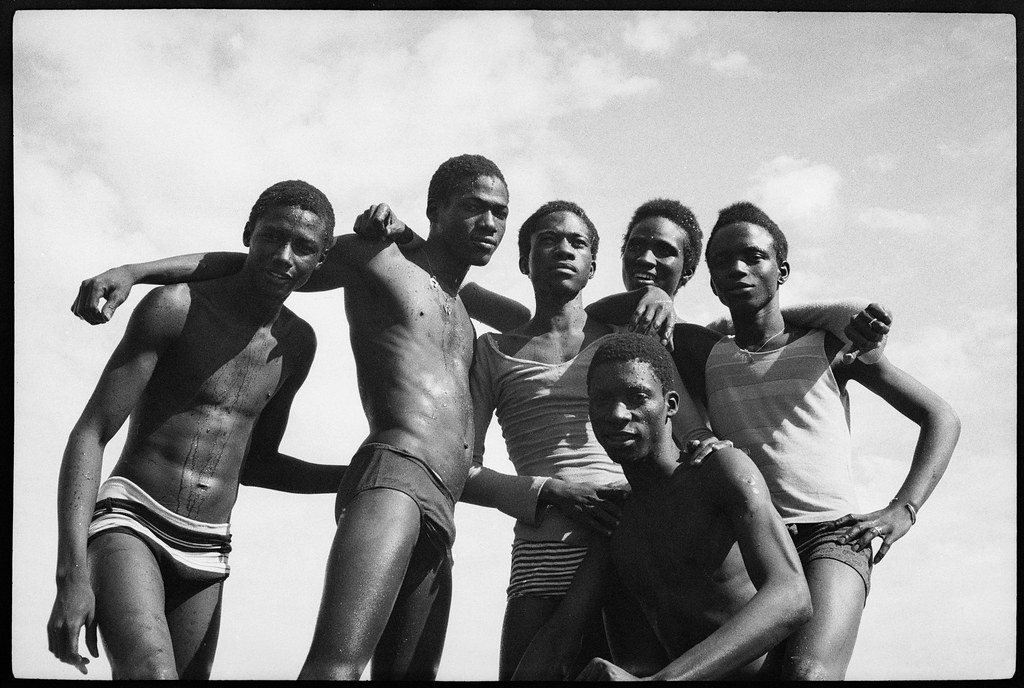

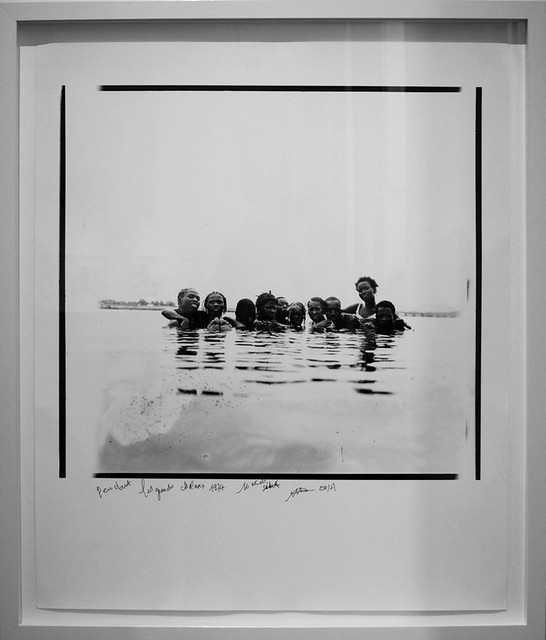

Top: A la plage, 1974 © Malick Sidibé. Courtesy Galerie MAGNIN-A, Paris.

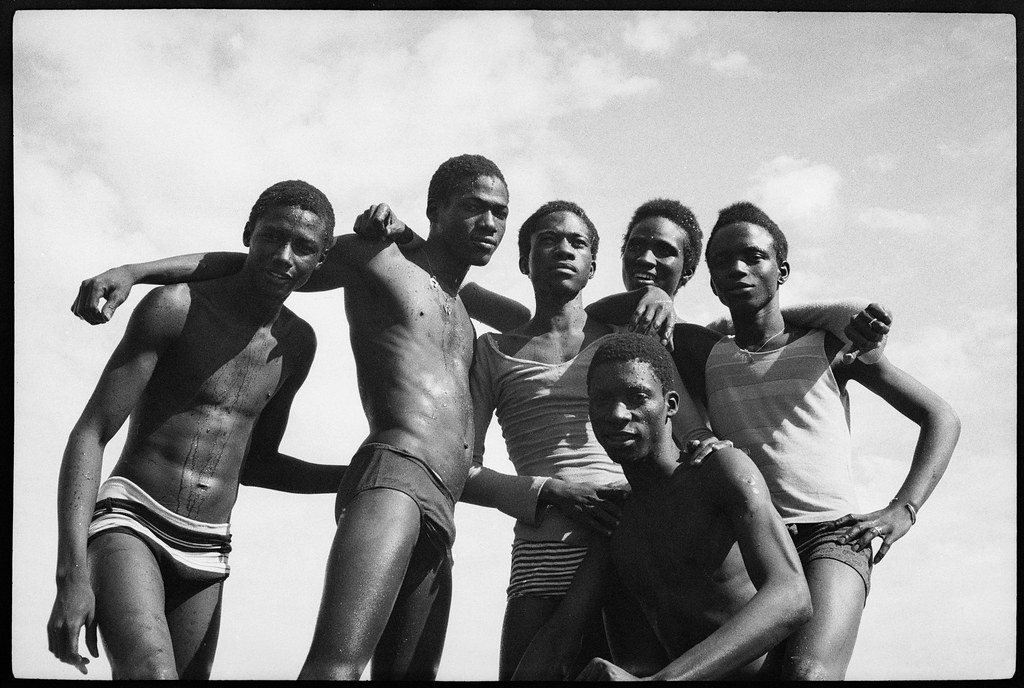

Dansez le Twist, 1965 © Malick Sidibé. Courtesy Galerie MAGNIN-A, Paris.

The first room Tiep à Bamako, shows scenes from the nightclubs where Sidibé began to develop his documentary style with a Brownie Flash camera. During the 1960s there was a new youth movement that emerged in Mali, partly inspired by the influx of western music. People were listening to James Brown and the Beatles and they were dancing the jive and twist.

As Sidibé recalled during a 2010 interview with The Guardian, ‘We were entering a new era, and people wanted to dance. Music freed us. Suddenly, young men could get close to young women, hold them in their hands. Before, it was not allowed. And everyone wanted to be photographed dancing up close.’ Sidibé would sometimes go to four or five clubs a night to document the styles and attitudes.

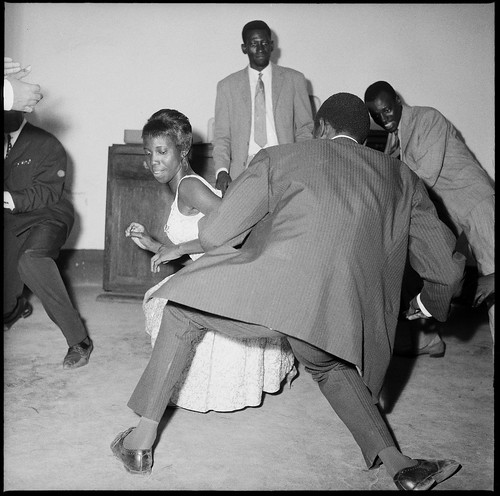

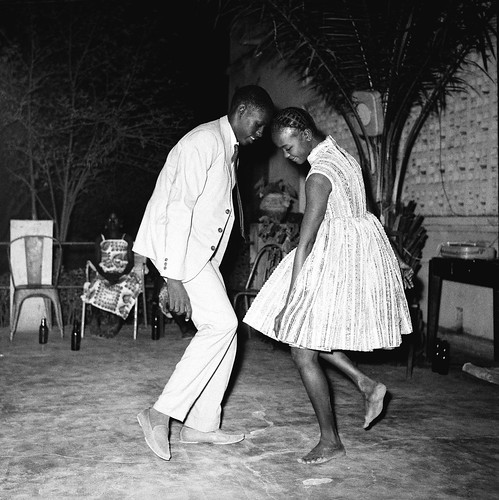

It was during this time that Sidibé took some of his best known photographs, such as Nuit du Noël (Happy Club), 1963, which shows a man and woman dancing close yet not touching, the woman barefoot in her dress and the man wearing a white suit, both with shy smiles. The picture captures the hopeful anticipation that was present during the decade, and the beauty of an intimate moment shared between the two dancers.

Nuit de Noël (Happy Club), 1963 © Malick Sidibé. Courtesy Galerie MAGNIN-A, Paris.

The second room continues the mood of ease, celebration and camaraderie, with photographs taken along the Niger River in the 1970s. Reminiscent of a beach party, the photographs depict snuggling couples, and friends who swim in the river and pose together.

Malick Sidibé, Pendant les grandes chaleurs, 1971.

Sidibé’s photographs included in the Au Fleuve Niger / Beside the Niger River section were taken in the 1970s.

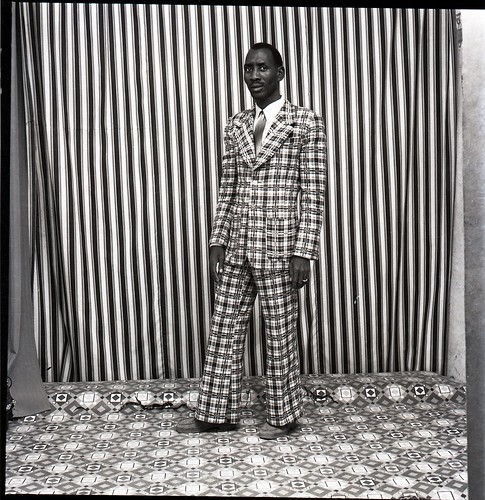

The last section shifts from the street photography style of the first two to formal portraits. The photos were taken at Sidibé’s Studio Malick, which he opened in 1962 after leaving his apprenticeship with Guillat-Guignard. Sidibé described the studio as a party. He would encourage clients to bring props such as hats, guitars or favourite record albums with them for the photos, and would then arrange them in ways that brought life and action to the images, continuing the themes of energy and movement that are felt throughout the exhibition.

The final collection Le Studio / The Studio includes portiats taken at Sidibé’s Studio Malick in Mali between 1960 and 2001.

A moi seul, 1978 © Malick Sidibé. Courtesy Galerie MAGNIN-A, Paris. Some of his photographs from this period were used for CD and album cover art (See ‘Noted #40’ on the Eye blog).

Even after Sidibé gained international fame in the 1990s, he continued to live and work at his small home in Bamako. He became the first photographer – and the first African artist – to receive a Golden Lion award at the 2007 Venice Biennale.

Sidibé once said, ‘It’s a world, someone’s face. When I capture it, I see the future of the world.’ Sidibé is remembered for his photographs that documented the future of newly independent Mali through the faces of its young people. Somerset House’s ‘The Eye of Modern Mali’ expertly weaves together Sidibé’s images with electrifying music to bring to life a vibrant period of African history.

Mariam Dembele, journalist, Temple University, Philadelphia

Malick Sidibé: The Eye of Modern Mali exhibition continues at London’s Somerset House until 15 January 2017. Photographs of the installation by Mariam Dembele.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.