Wednesday, 1:00pm

7 October 2009

Framing the evidence of war

An ambitious hybrid combines graphic novel with photojournalism.

If a book like The Photographer already exists (cover pictured above), I have certainly never seen it, writes Rick Poynor. This three-way collaboration between the late French photographer Didier Lefèvre, graphic novelist Emmanuel Guibert and graphic designer Frédéric Lemercier is a breathtakingly

original piece of work that reveals new possibilities for a medium, the graphic novel, that still divides readers into two camps. There are those who enjoy them, and those – especially in the UK – who can’t shake the feeling that to be caught with your head in a comic book would mark you forever as an emotionally stunted post-adolescent, no matter how often we are told that the graphic novel came of age years ago.

I’m a selective enthusiast, a dabbler in the rarer comic book pleasures rather than a full-time convert, but I’m still happy to throw in my lot with the first group. If you are concerned with graphic communication, how could you not be interested in a medium that unites writing, illustration and page design in the service of a continuous narrative? The Photographer supplies a new level of aesthetic complication and a new argument for the vitality of comics by adding a fourth strand to this mongrel medium: photography.

Above: After an arduous night of walking, Lefèvre compels himself to take pictures of the early morning campsite.

The book was first published in French in 2003 and it has sold 250,000 copies in the French-speaking world. Now it arrives in an English translation (by Alexis Siegel) published by First Second in New York.

In 1986, Lefèvre undertook a gruelling assignment with Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders), travelling overland from Pakistan with a group of medics into Afghanistan, where the mujahideen were then at war with the Soviet Union. It was his first project as a photojournalist and he took pictures at almost every stage of the journey. Six of the photos were published in the French newspaper Libération later that year. Several thousand remained in storage, unseen, until Guibert, who had heard stories about the trip, suggested to his friend that they collaborate on a book about it.

Above: Travelling back to Pakistan, Lefèvre attempts to make conversation with the aid of a dictionary.

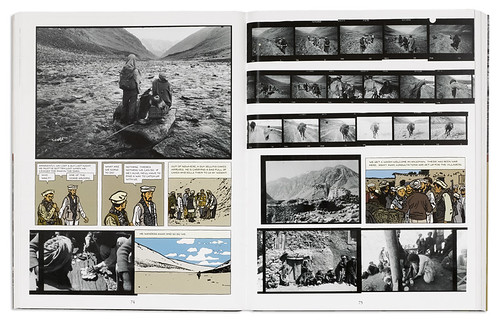

Guibert’s masterstroke is to present the photos as panels in the narrative. Where even a generous photo-essay in a magazine would need to be highly selective, this allows incidents caught on camera to be presented sequentially from multiple perspectives, building a much fuller sense of a scene than would ordinarily be possible. Guibert then supplies linking moments: sometimes just a panel or two, where an incident has been photographed in detail; sometimes much lengthier sequences, where no pictures exist. He never attempts to upstage the photographs with over-elaborate drawings – they are sensitively coloured by Lemercier – and it is a measure of the shared understanding between the collaborators that the links never seem artificial or forced. One can move seamlessly from photographic evidence, in which all the characters and occasionally Lefèvre appear, to fictional reconstruction (in scale with the photos) with no sense that ‘reality’ has been violated. The feat is all the more remarkable because Lefèvre lost the notebook in which he had recorded his observations throughout the journey.

The Photographers’s narrative density is highly involving. The journey on foot through difficult terrain is long, arduous and sometimes brutal. One of the horse grooms goes missing in the dark, while crossing a pass, and is presumed lost. He reappears in the morning against the odds, and Lefèvre captures the look of terror on his face. The pages devoted to the doctors’ labours at the makeshift ‘hospital’ at Zaragandara, with the booms of battle alarmingly close, are extremely moving. Lefèvre, aided by Guibert, shows us the doctors, who are able to cope with the most trying conditions, emptying out the socket of a man’s shattered eye and treating the burned hand of a small girl – an incident recorded with a sequence of twenty photos.

Above: A donkey rests during the crossing of a shallow but fast-flowing river. On the previous page (not shown here) Lefèvre's contact strips document his struggle to capture the picture he wanted.

One might argue, as some have, that photojournalism of this kind is intrusive and voyeuristic, though such scenes are taken for granted in TV documentaries. But MSF’s work continues in war zones around the world and The Photographer provides a brilliantly revealing document of its desperately needed efforts. The book’s international success is a welcome sign that there is an audience hungry for photographs that tell us something we urgently need to know about the world (see ‘One week in pictures’, in Eye 73).

With his film running out, Lefèvre chose to try to find his way back to Pakistan on his own. Exhausted and malnourished, he was lucky to get out alive. He made seven more photographic trips to Afghanistan before he died of heart failure in 2007 at the age of 49.

Above: Wounded Afghans, including a boy of two or three, are laid out on the floor of a bakery.

This Critique by Rick Poynor was first published in Eye 73, Autumn 2009. You can read all Rick’s Critiques here on the Eye website.

Eye is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop. For a taste of the magazine, try Eye before you buy.