Tuesday, 5:38pm

4 October 2016

Giancarlo Iliprandi (1925-2016) [LINK]

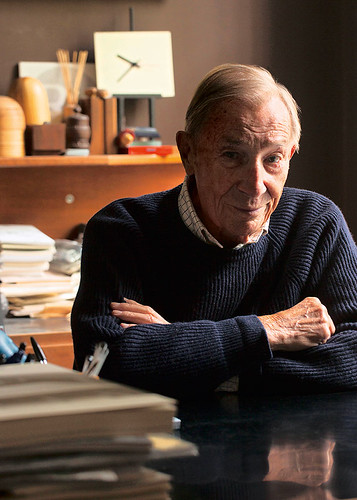

A recent interview with the distinguished and prolific Milan designer, who died on 15 September 2016 at the age of 91.

In the summer of 2015, Giancarlo Iliprandi came to London for the Fedrigoni-initiated exhibition Made In Italy (designed by SEA), which featured his posters and other work from the AIAP archive. Mr Iliprandi attended the private view, drinking red wine, signing posters and chatting happily in excellent English. The following day he sat down with John L. Walters, editor of Eye and Pulp magazines, for an extensive feature about his long career. The following text was first published in Pulp no. 6 in 2015.

Read the full text here, eyemagazine.com/blog/post/giancarlo-iliprandi-1925-2016

Giancarlo Iliprandi in 2015. Portrait by Andrea Basile.

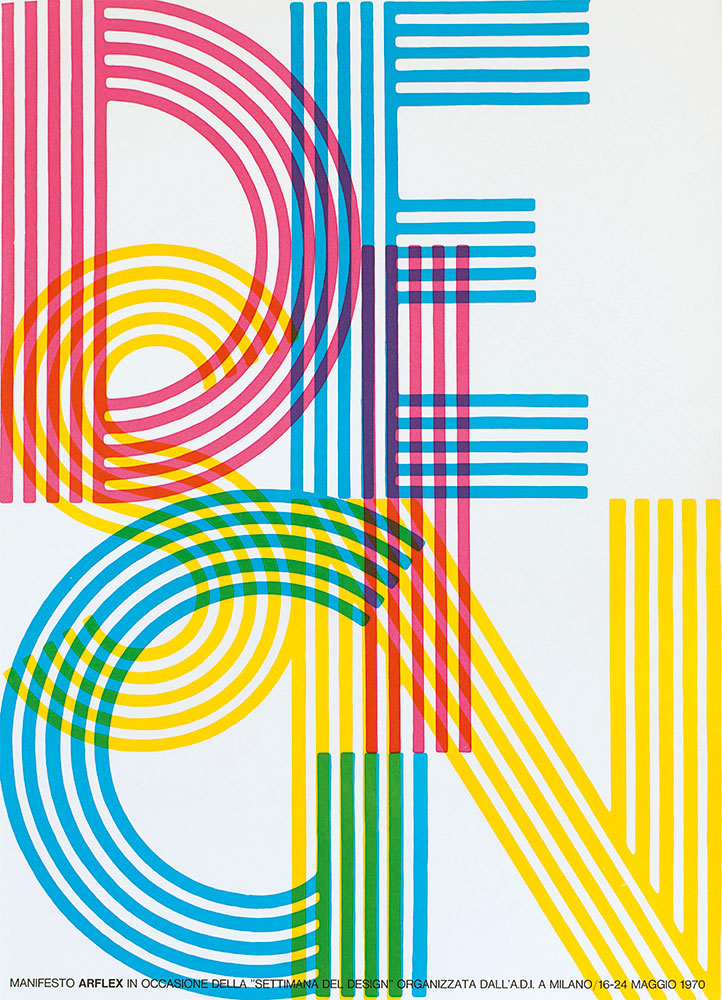

Top: One in a series of posters Iliprandi designed for Italian furniture manufacturer Arflex, 1970.