Monday, 11:01am

14 September 2015

Hans Unger centenary exhibition

Naomi Games remembers ‘Uncle’ Hans Unger (1915-75) in anticipation of a show of his work at the Highgate Society

I do not know how Hans Unger became friends with my parents but he was always very much a part of our family. When he visited our house, (and he visited often) the three Games children were excited, writes Naomi Games.

‘Uncle’ Hans was exotic and we loved him. He arrived by bicycle with a huge smile, a good sense of humour and with a lighted cigarette always attached to his elegant hand. He had no children, so he borrowed us and took us on adventures in his sports car. My parents had no car, but they did have a large colourful Unger mosaic taking pride of place on the living room wall. We could never work out what the image was of, but we liked it and still cherish it.

Mosaic by Hans Unger and Eberhard Schulze, given to the Games family.

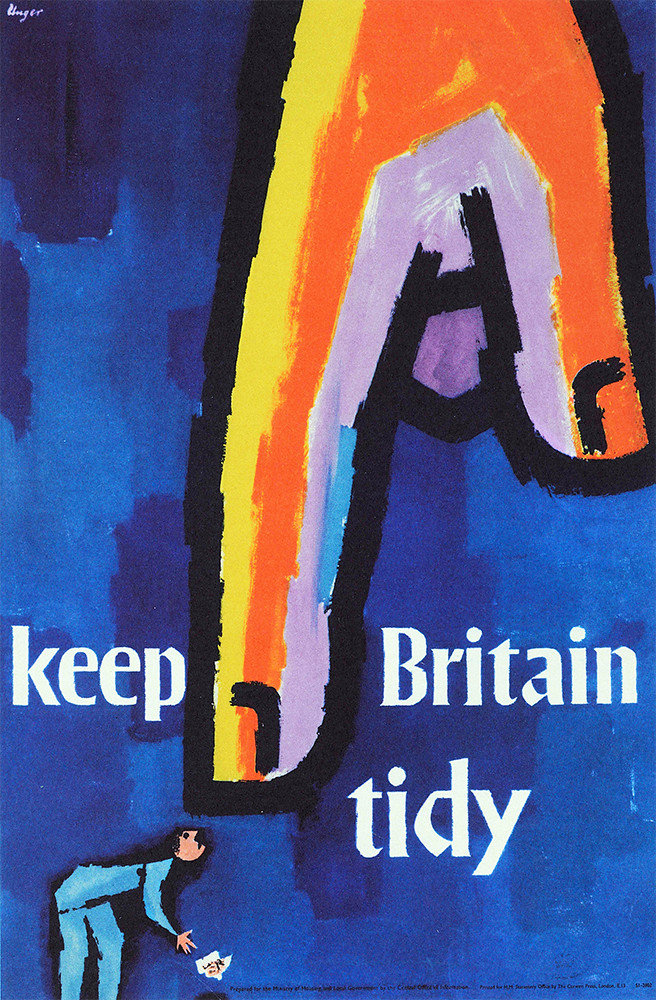

Top: ‘Keep Britain Tidy’, 1962.

Hans Ernest Unger was born in Prenzlau, East Germany on 8 August 1915. The son of a lawyer, he studied medicine in Berlin until Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in 1933. Like so many Jews, Unger’s ambitions were thwarted by the arrival of the Nazi party, so he travelled to Italy settling in Siena, and spent a year taking photographs. Surprisingly, he returned to an unsettled Germany and studied with Jupp Wiertz, one of Berlin’s most prominent poster designers. In 1936, realising that it would become impossible to remain in the country of his birth, Unger emigrated to South Africa, securing a job with the Cape Times. While there, he won two poster competitions for the Post Office and the Port Elizabeth Travel Association, giving him the confidence to make graphic design a career.

Right: ‘Keep in touch with your friends at sea’, Royal Mail Group Ltd., 1951, courtesy of the British Postal Museum & Archive.

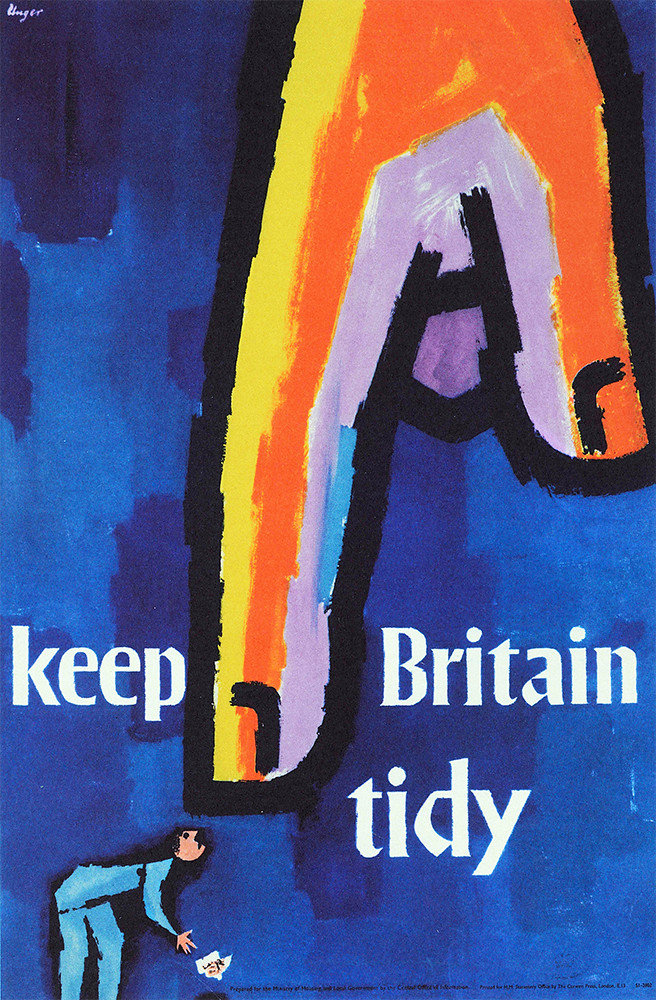

Right below: ‘Post Early’, Royal Mail Group Ltd., 1964, courtesy of the British Postal Museum & Archive.

—

The British Postal Museum & Archive is building a new, national museum showcasing its world-class collections charting five centuries of communication and social history. The Postal Museum, located in Central London, will reveal the extraordinary stories of global ingenuity undertaken by the Post Office and the constant endeavour to keep people across the globe in touch.

When the Second World War began in 1939, Unger volunteered for the South African army and became a gunner in an anti-aircraft battery. Four years later, while defending Tobruk in Libya, the Germans took him prisoner and sent him to a prisoner-of-war camp in occupied Italy. (Camp 52 in Chiavari was eventually transferred to Germany and joined Stalag VIIIB in Upper Silesia.) While there, he designed many posters to advertise the camp shows with material provided by the Red Cross. But Unger was a German Jew and he realised he would eventually be shot, tortured or sent to an extermination camp so he resolved to escape.

It is said that he escaped by jumping from a moving truck, hurling himself over a cliff and hiding in the mountains. I have also heard that during the escape he carried a wounded soldier on his back to safety, but I cannot verify this. With the help of the French Resistance, he joined a group of allied prisoners of war, crossing the Pyrenees into Spain and then into Portugal, by foot, in the winter of 1943-44. But Arctic conditions prevailed and the ill-equipped Unger suffered frostbite and lost some toes. When he visited London in 1944, King George VI invested him with the Military Medal for gallant and distinguished service.

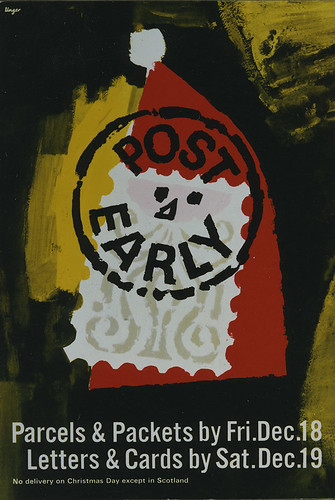

Unger returned to South Africa but was invalided out of the army. Like many other émigré designers, he thought his work prospects would be better in Britain, so he moved permanently to London in 1948 and sought naturalisation. His reputation as a top poster artist was quickly established and soon his distinctive signature appeared on posters for the General Post Office, the ‘Ideal Home’ exhibition, the Observer, British Rail and London Transport. In 1957 my father Abram Games, then art director of the experimental Penguin colour covers (see ‘Books received #2’ on the Eye blog), commissioned Unger to design three covers for the series.

Penguin book cover for Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Drowning Duck, 1956-1957.

Unger told the Journal of the Society of Industrial Designers: ‘I find it stimulating and exciting to experiment with new techniques and contrasting textures which will in turn interest the onlooker. With the aid of numerous test scribbles I try to find an appealing, forceful, interesting or perhaps humorous way of presenting the point and a simple way of interpreting the message in visual terms.’

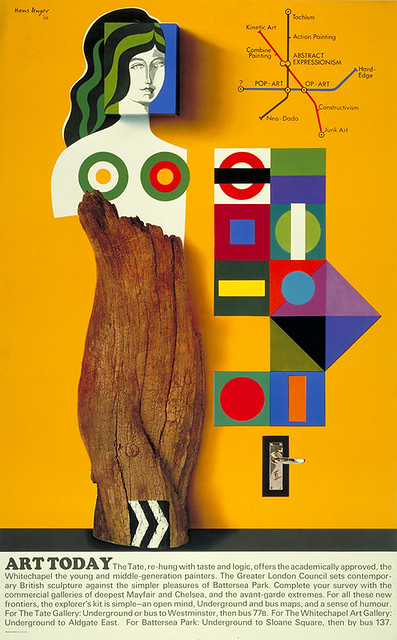

Art Today poster, 1966. © TfL from the London Transport Museum collection.

But he was restless, and cycled through Europe and the Near East in 1959, taking many photographs and seeking inspiration. His final destination was Iran. On return six months later, he set up a studio with German-born Eberhard Schulze to produce mosaics and stained glass windows. Unger had learnt the required techniques while visiting traditional studios on his travels in Italy. The two friends fused stained glass and ceramic, which they combined with traditional Venetian glass smalti, and they experimented with new materials and processes. Numerous commissioned mosaic murals were produced for corporate and public buildings and their stained glass windows were installed in many churches in the United Kingdom and in the United States. Unger was lucky to escape with only two broken legs when a huge, heavy, metal mosaic frame fell on him. He designed the projects and he and Schulze carried through the technical side. Schulze recalled something Unger said while designing a piece, ‘If the sketch takes longer than two days, it’s fertummelt (befuddled)’.

Both men signed the three dimensional work and Unger continued to design his posters, sometimes incorporating mosaics into the image. In 1964, Penguin books commissioned a mosaic mural for their staff canteen in Harmondsworth, West Drayton, (it has since been moved to Pearson’s Distribution Centre in Rugby). Measuring 4.1 x 2.6 metres, it includes pieces of slate and a collage of typefaces, colophons, printing blocks and linotype pages used for printing the Penguin books. The colours represent the different types of paperback series.

Penguin mural, 1964.

The team opened a small successful school in the studio of Unger’s small North London home and offered students a course on practical mosaics. In 1965, Studio Vista asked Unger to write the handbook Practical Mosaics. Unger and Schulze’s final collaboration was for the newly built Royal Free Hospital in Hampstead. Completed two years before Unger’s death, the hospital dithered about where to place the mosaic mural, which measured, 5.48 x 2.13 metres. He was devastated when 0.28 metres had to be trimmed at the bottom to make the mural fit into the allotted space. The delightful parkland scene was not unveiled until after his death. Eberhard Schulze retired due to ill health, left Britain and became a specialist aquarist. Every time I visit my local hospital, I touch the mural and smile.

Hans’s death in June 1975 at the age of 59 came as a huge shock. I was 24 and had become a designer myself. I loved Hans and admired his work so I suggested to my father, Abram, that an exhibition should be organised. He agreed and we proceeded to track down his work, which was uncatalogued and dispersed over many continents. Many friends helped and two years later, we held a commemorative exhibition in London for our dear Hans. Abram arranged for his archive to be given to the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Archive of Art and Design, and some of his work can now also be found in the archives of the Post Office and at the London Transport Museum.

Brixton tiles, Victoria Line, 1969. © TfL from the London Transport Museum collection.

A private man, Unger was often critical of his own work, he was unsentimental and outspoken but was always admired. After his death, Abram wrote in the Designer, ‘Hans’s individual techniques and colour sense were entirely new to the poster and his designs were eagerly sought by museums and collectors all over the world. Because he gave so much, his design will continue to grow in importance as ever increasingly the eye of the designer gives place to the camera.’

To this day, although he earned an international reputation as a designer and master of mosaics, I believe Hans Unger has never received the attention and accolades he rightly deserves.

A group of his friends are holding the ‘Hans Unger Centenary Exhibition’ from 10-25 October 2015 at the Highgate Society, 10A South Grove N6 6BS, London: Saturday 10-6, Sunday 2-6, Tuesday 2-6, Thursday 4-8.

Please check opening times before visiting. Tel: 020 8348 4082.

Hans Unger by his poster for BEA.

Naomi Games, designer & author, London

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.