Friday, 11:00am

4 December 2015

Illustration as anthropology

Laura Carlin

Darryl Clifton

Vallee Duhamel

Rachel Gannon

Pablo Jones-Soler

Anna Lomax

Robert Nicol

various designers

Illustration

New media

Reviews

Visual culture

Mut Mut

Assembly Point, 49 Staffordshire Street, London SE15 5TJ, UK<br> Weds – Fri: 12–6pm. Sat: 12–5pmIn Assembly Point, a new gallery space in Peckham, eleven illustrators take a critical approach to their practice

This exhibition of contemporary illustrators is a serious affair, writes Colin Davies.

The title ‘Mut Mut’ (according to the programme) is from the Latin phrase mutatis mutandis, meaning ‘the necessary changes having been made’. The show is in a beautiful white-cube gallery space, Assembly Point, which sits Tardis-like in the back streets of Peckham in South London.

Darryl Clifton and Rachel Gannon have sharply curated eleven illustrators, providing a vista of work that asks questions of what illustration might mean now and, importantly, how it might catalyse a physical world informed by the illustrators’ observational eye. Illustration at its best is, as this exhibition confirms, more anthropological than visual.

Nous Vous, Untitled (detail), 2015.

Top: Installation image of Assembly Point’s current exhibition ‘Mut Mut’ showing Rachel Gannon’s Dreamland, Cairo and ceramics by Darryl Clifton and Robert Nicol.

Nous Vous, Untitled (detail), 2015.

The illustrator has always taken on the role of participant observer in design: illustrators provide a psychological trace rather than simple record or mimesis. In this sense the authorial is embedded in illustration practice. But the practice is often obscured by traditional commissioning practices in which the illustrator is placed at the tail end of a production process.

In ‘Mut Mut’, the curators concentrate on illustration as 3D, material, and installational practice. Anna Lomax, who graduated as an illustrator in 1977, provides a humorous touch in her sculpture Maggie’s: a triptych of neon fried egg, Perspex chips, and a large fabricated upright wedge of tomato inspired by a café in Lewisham – both observational and humorous social commentary.

Anna Lomax, Maggie’s, 2015.

Peter Nencini’s Porphyric Hod is a series of tightly imagined and executed assemblages of objects, narrative-driven and compactly created. One piece, Porphyric Hod (C), is a 3D grid formed by a warped bathtub ‘caddy’ with a 1968 Penguin book, New English Dramatists 12, at its centre; domestic life radiates out: miniature coat-hangers, a cereal fruit loop, surreptitious cigarettes corking plastic shampoo bottles, bubble gum and dried spaghetti – all are included as the flotsam of late 1960s provincial life. Each piece has a perfect doppelgänger placed alongside – an ironic comment on the reproducibility of illustration?

Peter Nencini, Porphyric Hod i-iv.

Peter Nencini, Porphyric Hod i-iv (detail).

Pablo Jones-Soler, an illustration graduate from Camberwell School of Arts UAL, in Bench III plays with the translation from digital to physical. A steel bench mounted on a cement base is adorned with eBay-sourced ephemera. Cut into the steel bench are the tagging and initials of past sitters: industrial rather than visceral. The work plays with the binary between the digital / analogue; organic / industrial in the means of production.

Rachel Gannon’s display is positioned, panopticon like, near the centre of the gallery space. A carefully crafted table carries a collection of maquettes – Dreamland, Cairo – that depict the physical infrastructure of observation towers, ladders, and advertising hoardings. It creates a latticework of the architecture that supports our fetish for being viewed and viewing. Where Jones-Soler’s work is industrial and muted, Gannon’s ‘metalwork’ is made from painted cut balsawood. Each construction is tastefully painted: blue, black, acid yellow and neon red. The piece is both beguiling and disarming – the same engineering know-how constructs detentions centres, Guantanamo Bay and the ghostly advertising hoardings originally sketched in Learning from Las Vegas by Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi in the 1970s.

Rachel Gannon, Dreamland, Cairo (detail), 2015.

The exhibition also provides more conventional relationships for the illustrator: screen-based media and ceramics. Vallée Duhamel’s Very Short Film and Laura Carlin’s untitled ceramics are strong examples. Carlin’s beautifully observed and made work introduces the notion of craft, which is another strand of the exhibition’s remit. It reminds the viewer of another element close to the methodological heart of illustration: animation.

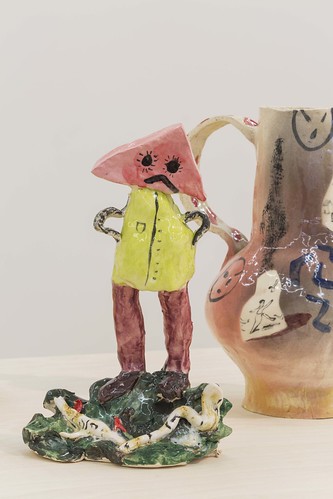

Darryl Clifton and Rob Nicol show ceramic work, too, collaboratively and individually, that uses craft as a process of intervention – exposing the legacies of making – rather than a holistic material extension to illustration.

From Laura Carlin’s ‘Untitled’ series of ceramics.

Works by Darryl Clifton and Robert Nicol.

The exhibition is not confrontational – it provides alternative developments in illustration by example rather than polemics, something that might be seen by some in design as a weakness. Critical thinking in design often reduces to simple binaries, bumptious and sloganeering rather than reflective, engaged and exploratory. This exhibition exemplifies the latter. It does signify a turn in illustration – a turn that must fully flesh out the meanings of the discipline, rather than simply take on the mantle of other artistic practices.

Maybe illustration could learn from the mistakes graphic design has made in trying to define a critical practice.

Pablo Jones-Soler, Bench III (detail).

Installation view.

Colin Davies, Reader in Design, Head of the School of Art and Design, University of Bedfordshire

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.