Thursday, 4:20pm

18 September 2008

Letter to the editor

various designers

Elliott Peter Earls

Allen Hori

Rudy VanderLans

Zuzana Licko

mike kippenhan

Design history

Graphic design

Magazines

New media

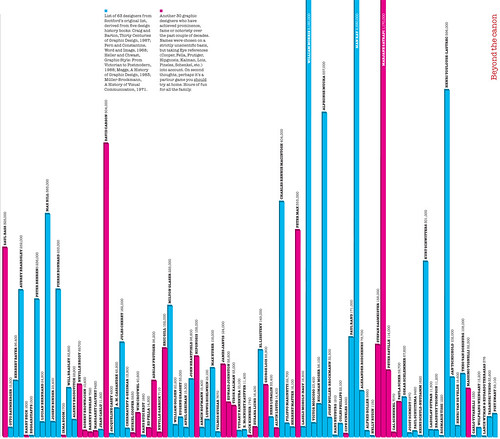

Re: Afterword to ‘Googling the design canon’ – don’t diss the digital

From Mike Kippenhan

The idea of inviting a variety of people associated with design to write about ‘neglected classics that take us “beyond the canon”’ resulted in an interesting and enjoyable issue of Eye (no. 68 vol. 17). It was refreshing to be introduced not only to some classics I was unaware of, but also to new contributors who have taken the time to share their ideas and interests.

Unfortunately, within this issue, I found Martha Scotford's ‘Afterword’ to ‘Googling the design canon’ troubling on a number of levels. While the premise of her original and current research is compelling, her broad generalisation of the differences between print and digital design history/writing is problematic. In the first two paragraphs Ms Scotford exalts all that is published on paper while dismissing all which is digital, thus creating a dichotomy of colossal and ridiculous proportions. In fact, I read the article numerous times and am still wondering, ‘Is this a joke?’ While one can no doubt find examples of ‘the perfect confluence of misinformation, disinformation and useless information . . .’ on the Web, I find it hard to understand how Ms Scotford believes she can dismiss the greatest dissemination of knowledge in human history because it did not go through the same (supposed) editorial rigor of the printed word.

Ms Scotford appears to be putting forth the notion that books somehow contain a depth of truth and understanding of subject that shorter, Web-based writing does not. It is as if it requires a combination of word count and physical form to make writing legitimate – just because an author’s ideas and words are captured in physical form, does that necessarily make them beyond reproach?

In this same issue, Rick Poynor (in his Critique, ‘Absolutely the worst’) clearly illustrates how two or three authors can elevate a piece of design, in this case an Alan Hori poster, to historical prominence. While Poynor is more than capable of presenting a scholarly argument as to why this poster is significant – both formally and historically – ultimately it was his choice to include it in his books. Therefore, his choice is based on his ‘opinion’ and it is ‘opinion’ that Ms Scotford demeaned in her characterisation of digital publishing.

Another example of how an author’s content choices can one day become part of the ‘canon’ is the inclusion of Elliott Peter Earls in Stephen J. Eskilson’s Graphic Design: A New History. I’m sorry, but a multimedia presentation (Throwing apples at the sun) and a few posters, all of which were unabashedly promoted by Emigre magazine, do not necessarily constitute Graphic Design History. (See Eye no. 45 vol. 12.)

And this leads to the question that if graphic design is primarily a client-driven commercial venture, how come so many history books have a disproportionate number of posters and self-published works, rather than client-based work? It does this discipline a disservice to incessantly promote these sorts of works as the ‘canons’ of design while relegating client-based work to the never-ending parade of incipient design annuals and contests. What does this say about our profession, Ms Scotford?

It appears that Ms Scotford is lamenting the fact that the traditional scholarly elite is losing its power and influence in determining the design canon to a new breed of authors and audience. In fact, it is individuals who believe in the legitimacy of digital publication that are injecting new ideas and new opinions into the discourse. One of the strengths of digital publishing is that it allows anyone to become an author and participant while also allowing immediate response and feedback. Of course this means we will find both the good and the bad; however, Ms Scotford should give us credit for being smart enough to figure these things out. The reality of the print publishing market (i.e. ‘known’ authors coupled with marketable / profitable subjects) combined with the time, effort and scholarly knowledge needed to write about design history results in few historical / critical design books being published. If we disregard and abandon Web publishing, what does that leave us? Unfortunately, Ms Scotford does not recognise that both the printed and digital word should co-exist and complement one another, it should not be an either-or.

Bozeman, Montana, USA

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.