Thursday, 5:07pm

15 August 2024

Lettering in the landscape

Mark Noad, Chair of the Lettering Arts Trust, considers the training and design behind hand-carved lettering and looks forward to two exhibitions of the carver’s art in the UK

Two questions are regularly levelled at letter-carvers: ‘what typeface is it?’ and ‘don’t you have a machine to do that?’ writes Mark Noad.

Well, in truth, they might make use of a typeface and yes, there are machines that can do it. But in the main, most letter-carvers practising today will be carving by hand the lettering they have drawn specifically for that job.

Letter-carving is all around us, from architectural inscriptions to commemorative plaques; from garden design to memorials in your local churchyard. The profession may go back thousands of years but it thrives today thanks to a growing community of skilled and dedicated practitioners who have taken traditional methods and brought them into the 21st Century.

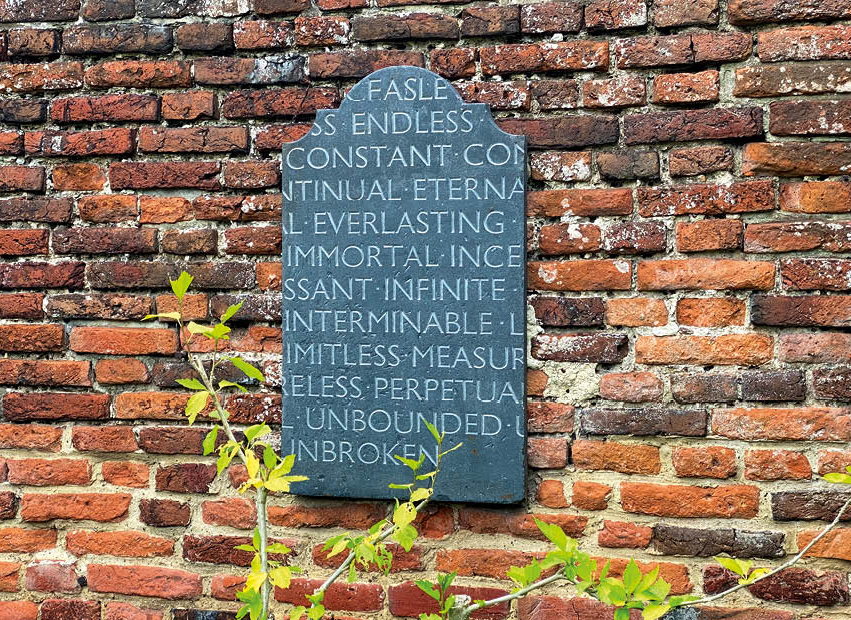

Right. Art & Memory Collection, Canterbury Cathedral. Artist: Lois Anderson.

Top. Apprentice Rachel Butler cutting a Roman alphabet at Eric Marland’s studio in Cambridge.

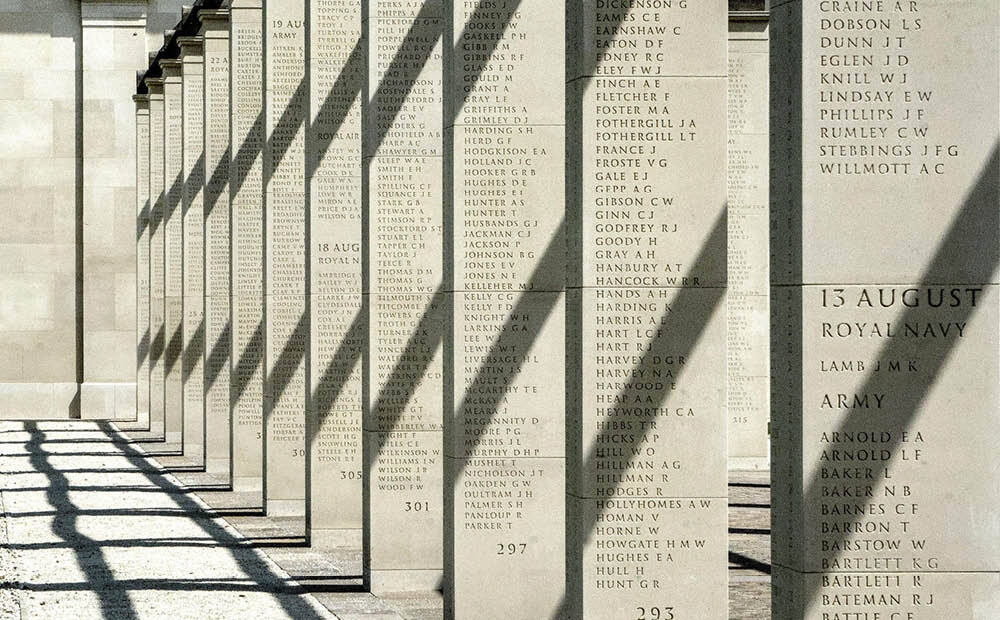

The British Normandy Memorial, 2021. Lettering by Richard Kindersley.

Lettering for the recently completed British Normandy Memorial was done by Richard Kindersley, one of the UK’s leading letter-carvers. He had been apprenticed to his father David Kindersley, who in turn was Eric Gill’s apprentice. The memorial – the biggest commission of Richard’s long career – required 23,000 names, a number that was not practical to cut by hand. His approach was to design a typeface to be cut mechanically into the stone. However the larger inscriptions on the memorial were done by hand, by a team of letter-carvers working in shifts.

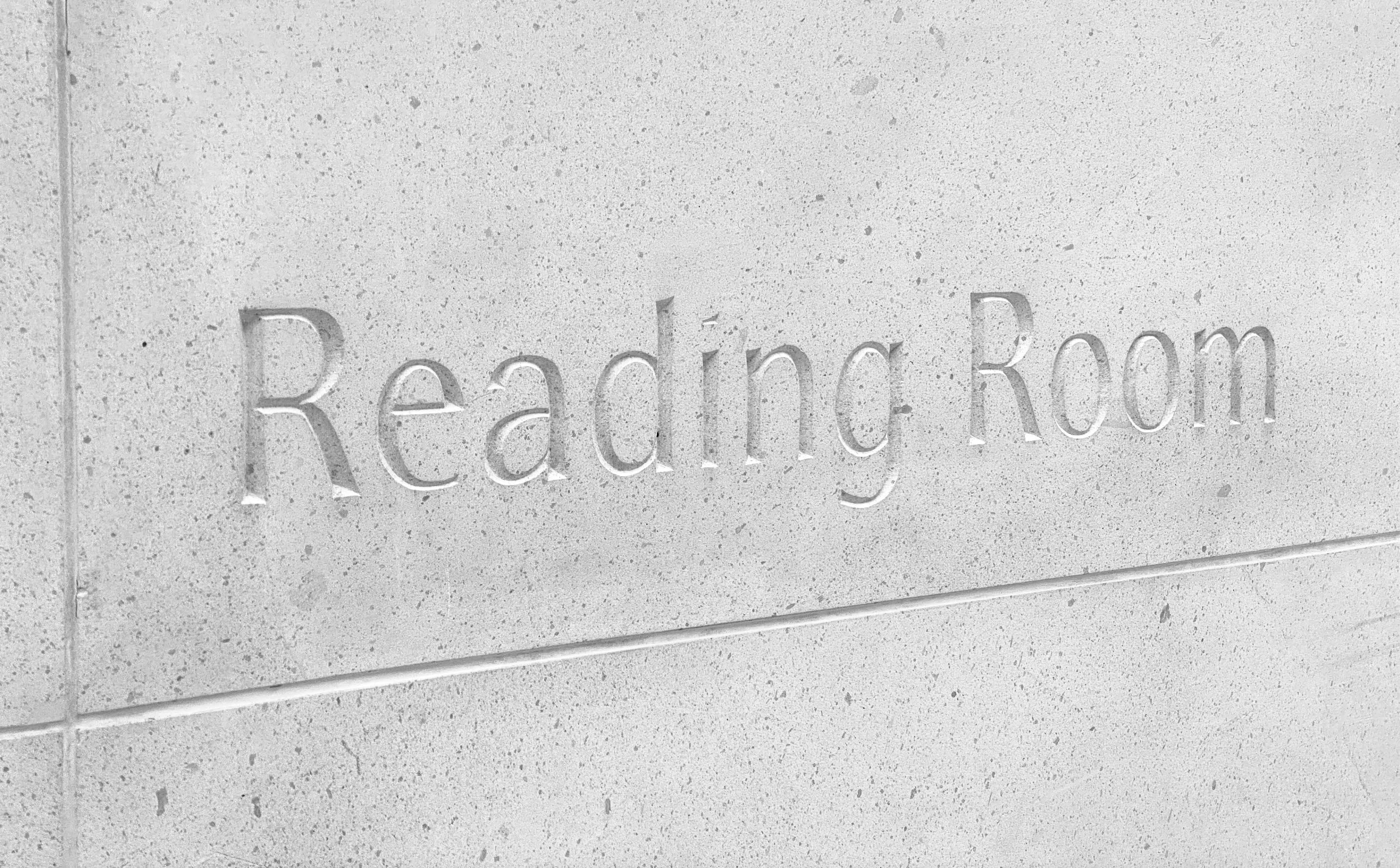

Lettering at the British Museum, London, by Martin Cook.

Typographers know that a typeface that works well as a text face is unlikely to be right for headlines or signs. Working in three dimensions, in stone, at large scale, this principle is magnified. When Martin Cook won the commission to cut the inscriptions in the Great Court of the British Museum, the architects wanted him to use the typeface Rotis. Although Rotis was originally designed for signs, using it at large scale and introducing a third dimension by cutting the face into the stone meant that Cook needed to change subtly the shape and proportions of each letter to make it work with a ‘v’-cut on a curved surface.

Further examples of Martin Cook’s lettering at the British Museum using Rotis, with modified dots on the ‘i’. BM photographs by Mark Noad.

Both Kindersley and Cook have a long association with the Lettering Arts Trust, the only organisation dedicated to preserving the craft of letter-cutting. Thanks to the work of the Trust, letter-carving has recently been removed from the Heritage Crafts Association ‘red list’ of endangered crafts. The Trust focuses on three things: the ‘Memorials by Artists’ service helps connect commissioning clients with the right artist; the Trust provides training and support for aspiring carvers; and it promotes the craft of letter-carving through exhibitions and other activities throughout the UK.

There are two levels of training: apprenticeships, two years working under a master carver learning all aspects of becoming a professional carver; and journeyman awards for short, intensive study on specific aspects of the craft – especially letter design. The Trust’s two current apprentices, Rachel Butler and Maia Gaffney Hyde, are coming to the end of their second year studying with Eric Marland and Charlotte Howarth respectively. This year [2024], five journeyman placements have been awarded to aspiring professional carvers, all female.

A Lettering Art Trust carving workshop, 2024.

Apprentice Maia Gaffney-Hyde says: ‘The ability to carve with more confidence has, from my perspective, been the biggest leap forward in my journey to becoming a letter-carver. I have become acquainted with how lettering can work as a business; from how and where to order stone; and how to engage with clients. Crucially, this first year has been an amazing opportunity to experiment.’ Gaffney-Hyde is based at Charlotte Howarth’s studio in North Norfolk (West Acre).

It is during their training that letter-carvers develop the skills that make what they do so special. For each commission, especially for memorials, they work with a client to develop a design that is unique and personal, crafting letterforms that sit comfortably together and are right for the material and scale to which they are working. The letters – Roman, italic, rustic, uncial – are incised with a ‘v’-cut in the stone using a chisel, leaving traces of each blow of the mallet – a visible connection to the hand of the maker. Apprentices also learn to select materials – slate, limestone, sandstone – that are appropriate for the surrounding landscape.

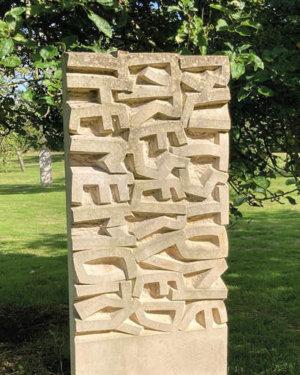

Stone Memory, 2009, by Charles Gurrey at the Art & Memory Collection, Grimsthorpe Castle, Lincolnshire. The text is the last line of Pablo Neruda’s poem ‘The Creation’.

Central to promoting the craft is the Art & Memory Collection, the Trust’s national collection of examples of the carver’s art. Set up in 2008, it currently comprises nearly 70 works displayed at six locations: Arnos Vale, Bristol; Blair Castle, Perthshire; Canterbury Cathedral; St Peter’s Church, Corpusty, Norfolk; Grimsthorpe Castle, Lincolnshire; and Winterbourne House, Birmingham. In September a new addition to the collection, by artist Dan Meek, will be unveiled at Winterbourne House as part of their Birmingham Honey Festival (and will have a suitably bee-related theme).

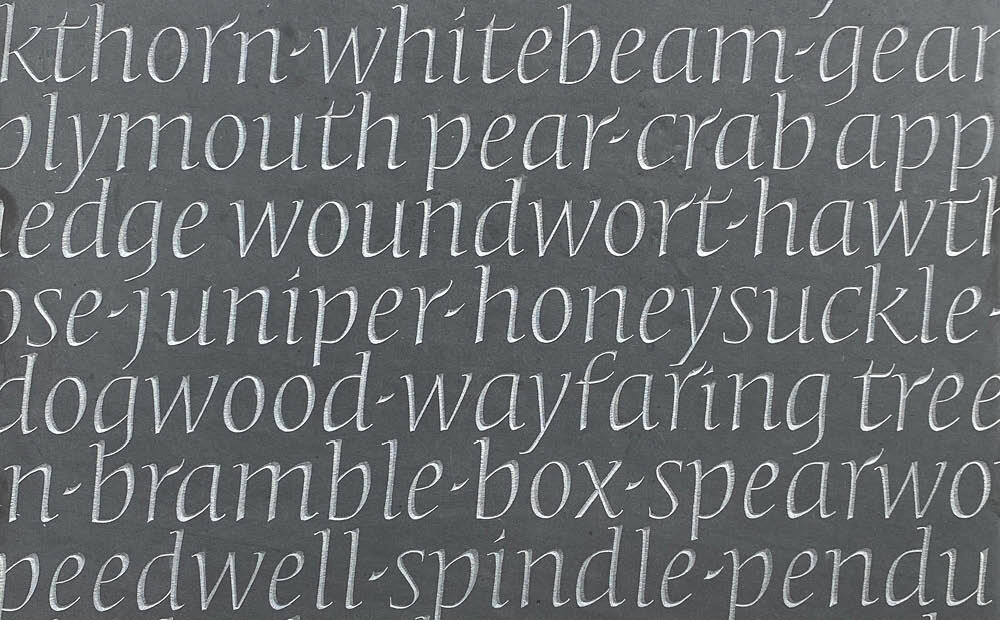

Connected Habitat (detail) by Fergus Davidson, which will be featured in the ‘Grown From Stone’ exhibition, 2024.

Wildflower Meadow by Louise Tiplady, to be featured in ‘Grown From Stone’.

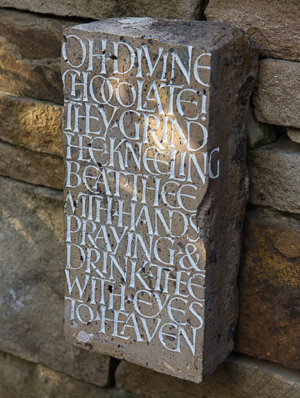

Divine Chocolate, by Mark Brooks, to be featured in ‘Grown From Stone’.

At the same time, Winterbourne House will be hosting the ‘Grown from Stone’ exhibition featuring work by Lettering Arts Trust artists. The Trust supports aspiring carvers through its training programme but also by providing opportunities for artists to exhibit, maybe for the first time. ‘Grown from Stone’ will feature current and former apprentices alongside established master carvers and runs from 24 August to 27 October 2024.

The Trust is also putting on an exhibition as part of the Bloomsbury Festival in London in October. ‘26 Connections’ is a collaboration with writers’ group 26 and the Barbican Young Poets, and will include work by letter-carvers alongside calligraphers and designers. It runs from 17 October to 14 November 2024 at the Building Centre in Store St., London.

Memorial by Dan Meek, 2018.

After more than 30 years, the Lettering Arts Trust continues to promote the craft of letter-carving and to train the next generation of carvers. Apprentice Rachel Butler says, ‘I’ve been involved with meeting clients; the design process on commissions; site visits; helped with installing stones; completed my first alphabet (which involved many aspects such as preparing the stone, drawing, carving, painting and gilding); and started my next alphabet – Roman Capitals. Every day there has been something new to learn.’ Butler is based at Eric Marland’s studio in Cambridge.

Letter-carving continues to play a unique role in our lives – it is an enduring expression of human connection to time, place, nature and each other.

Mark Noad, designer, Chair of the Lettering Arts Trust

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.