Monday, 12:03pm

15 August 2011

Make, do, mend

The revolutionary power of new micro-manufacturing technologies

Last Wednesday’s Future Human event explored the recent expansion of one-off manufacturing and rapid prototyping technologies, setting out with a bold claim: ‘Over the next ten years, we’re going to see digital economics upturn industrial production and the physical world of “things”’. Of course, there’s nothing new about micro-manufacturing, or bespoke one-offs, writes John Ridpath.

As opening speaker Jack Roberts reminded us, this is exactly what artisans and craftsmen were doing way back in the age of the guild. But back then, of course, the economics were inefficient.

Above: Panel discussion with Soner Ozenc, Assa Ashuach, Brendan Dawes and Oliver Beatty (L-R)

Mass production has its roots in the Industrial Revolution led by Britain, which saw increased production capacity thanks to new technologies, and culminated in the development of repetitive flow production in the twentieth century. These shifts had massive social ramifications as well as economic ones, with the average working week shooting down from 70 to 40 hours. The theory advanced by the organisers of this Future Human event, is that new advances in micro-manufacturing technology will usher in a new – and equally empowering – industrial revolution.

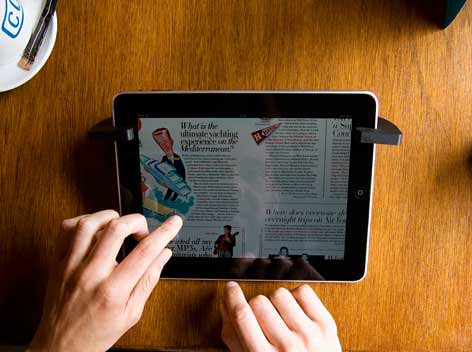

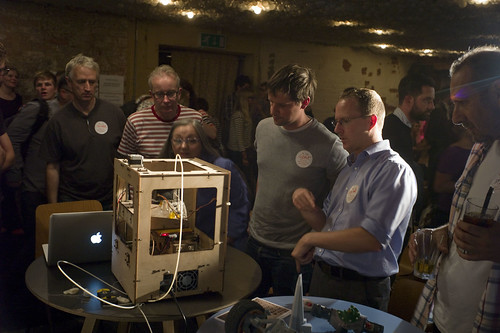

As for the new technologies on offer, speaker Brendan Dawes talked through his own experiments with 3D printing. A personal desire for a small device to prop up his iPhone on train journeys, inspired Dawes to design a small and fiendishly simple plastic stand, which he prototyped on a MakerBot 3D printer – an affordable device designed for home use, available as a kit for geeks and enthusiasts. Dawes’ colleague at Beep Industries suggested that his invention could be sold, and the product came out on the market as the MoviePeg (now available for iPhone 3 and 4 models, and the iPad; see below).

Paul Armand from Inition showed a more advanced level of production in his talk. His company’s printers cost upwards of £25,000 – pretty hefty, compared to MakerBot’s £800 entry-level price tag. However, these devices allow a quality, speed and variety of materials way beyond a DIY approach. Armand showed several examples of practical objects the studio had produced, including architects models and a working wrench.

Oliver Beatty chaired the second half of the evening, a discussion about whether the micro-manufacturing movement will disrupt the era of mass production. Guest speaker Assa Ashuach, a designer and additive manufacturing specialist at Digital Forming, argued that in this new age, the role of the designer will become more crucial than ever. Product designers of the future will provide consumers with a set of parameters for products, allowing customisation that manages to go beyond simply choosing a new colour, but rigid enough to always produce usable, aesthetic and ergonomic products. Giving everyday users a carte blanche to create things is all very well, but if we want to be producing useful things, professionals will need to guide them. Otherwise, as Dawes pointed out, putting these tools into the hands of everyone could result in a glut of poorly designed objects: ‘you can make 100 cat’s bum-shaped pencil sharpeners if you want.’

But in the sweltering heat of the The Book Club’s basement, audience participation began to take on a slightly riotous air. A minority of shouty attendees took issue with these ideas, angrily suggesting that the panel of designers were trying to quell the subversive power of this technological revolution. One of the final questions even suggested that this new industrial revolution is distinctly Marxist in ideology. After all, weren’t we all talking about the people owning the means of production?

Above: A MakerBot printer produces a MoviePeg during the first half of the Future Human event

But the distinction between design and manufacture is crucial here. Even if people will soon be manufacturing in their own homes (or local communities, as guest speaker Soner Ozenc suggested), the masses will not be designing new products from scratch. Most will download other people’s 3D schematics, with a limited amount of tinkering – and whether digital designs will be paid-for or pirated turns out to be a more prescient, if predictable, debate. Another interesting subject emerged, as mentioned in Future Human’s debrief: ‘could the decline of mass manufacturing lead to a decline in the kind of acquisitiveness and thrall to brands that has driven the looters?’

But others felt that the future is less revolutionary, with @edsaperia tweeting: ‘Personally I think this all misses the point. Individuals can always find quick fixes, bit the point is this tech allows good inventions/designs to arbitrarily scale to other consumers.’ The discussion is set to continue in Future Human’s forthcoming podcast.

For more on 3D printing (and making digital experiences more tangible), see ‘Tangible digital’ in Eye 80.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It’s available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop. For a taste of the current issue, see Eye before you buy on Issuu. Eye 80, Summer 2011, is out now.