Wednesday, 5:59pm

1 May 2013

Mapping Asmara

Steven McCarthy examines the way maps represent Eritrea’s capital city, Asmara – from architectural gems to military legacy

Unable to find a map of Asmara prior to my trip to Eritrea, apart from the page-sized version in a Lonely Planet guidebook, I made several screen grabs of Google maps in progessive levels of detail and saved them as images on an iPad, writes Steven McCarthy in his second report from Eritrea.

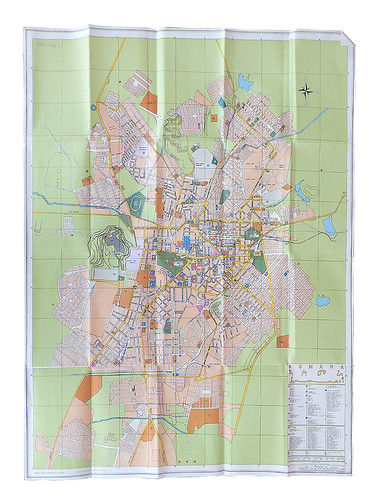

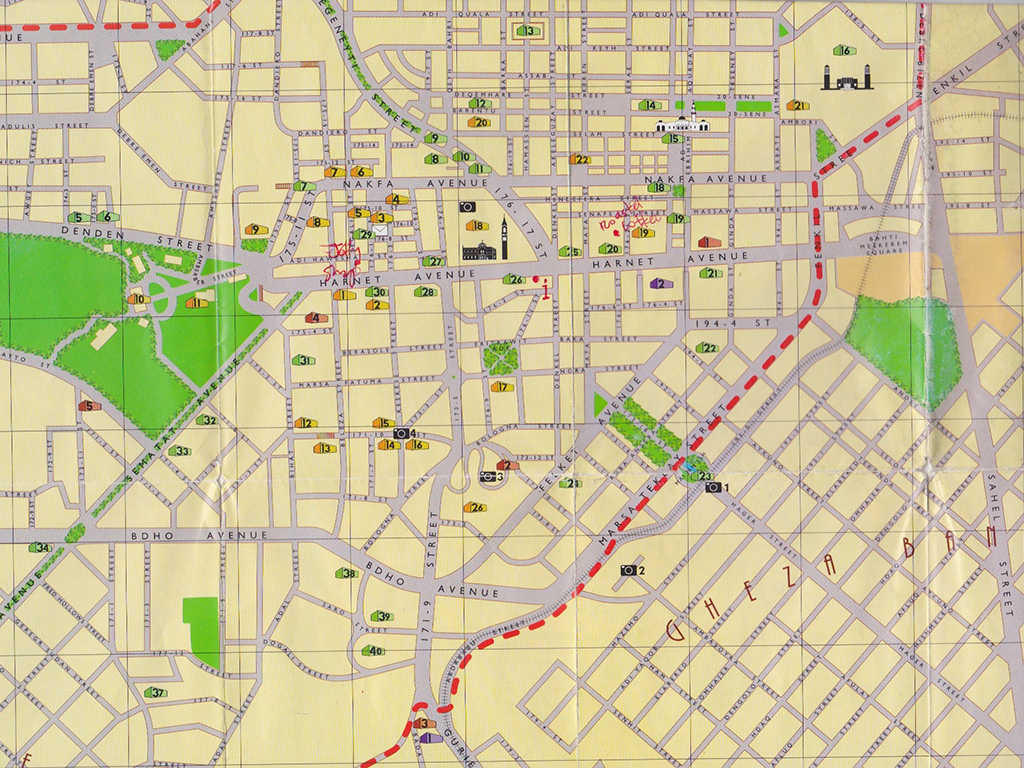

This was to be a temporary solution, as I prefer printed maps to screens. When I inquired at the Asmara Palace Hotel reception, the clerk produced a large city map. Poorly printed, it dated from 1994, just a couple years after Eritrea’s independence from Ethiopia and lacked much current information, such as many street names and my hotel location. It also lacked tight registration and fine detail. An architecture firm was credited with its design. In spite of the map’s flaws, I was told that it was the hotel’s only copy, and ‘No’, the clerk did not know where I could find another.

1994 map of Asmara.

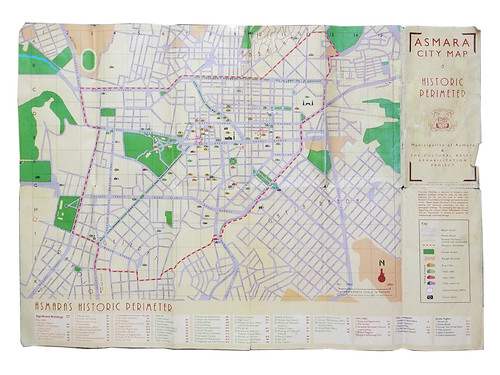

Top: detail of 2003 map.

Later that day, while walking down Asmara’s main boulevard, Harnet Avenue, a fellow approached me with ‘Pssst … wanna buy a map?’ I replied that I did, but found his price a bit too high. Walking away, I offered half, and the sale was made. His map inventory was neatly tucked inside his blazer, a staple garment of Asmarino gentlemen.

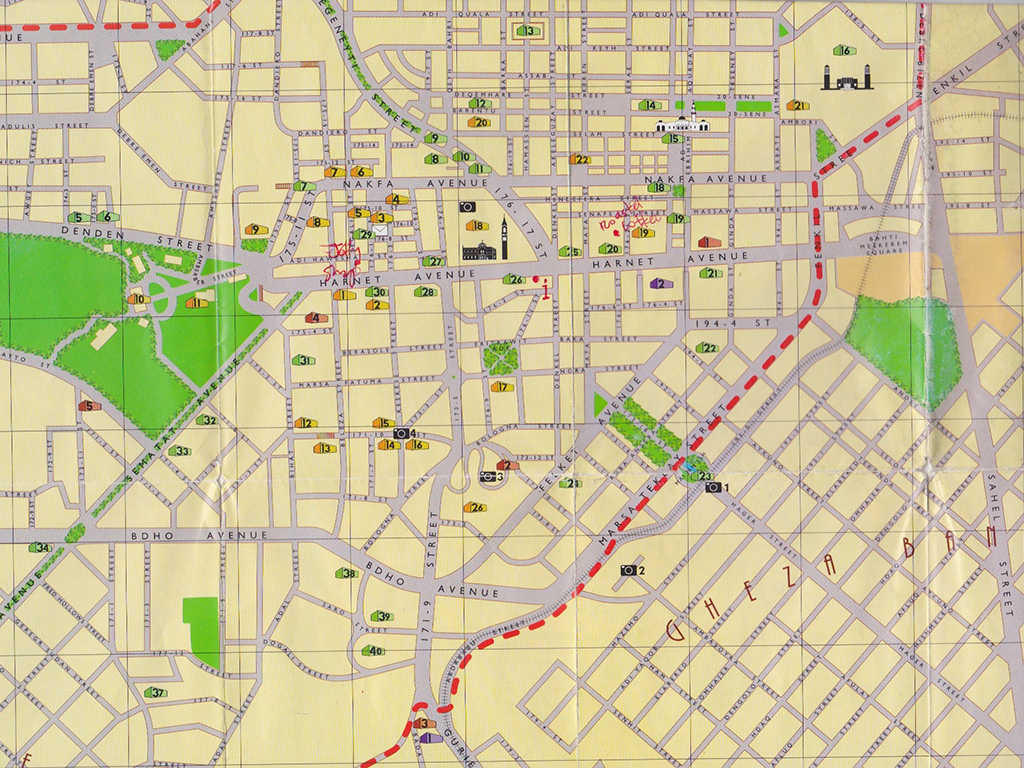

It may have been the find of my trip. ‘Asmara City Map & Historic Perimeter’ was printed in four-colour process, and is two-sided with the urban area on one and a detailed zoom of downtown on the other. It features names, locations and dates of Asmara’s many colonalist buildings – in particular, the notable Italian Modernist structures from the 1930s and 40s.

Authorship of this 2003 map is credited to the Municipality of Asmara and Eritrea’s Cultural Assets Rehabilitation Project (CARP), and names Edward Denison and Guang Yu Ren as designers. The duo also photographed, designed and co-authored, with former CARP head Naigzy Gebremedhin, the book Asmara: Africa’s Secret Modernist City – I fleetingly saw a copy inside my street vendor’s blazer.

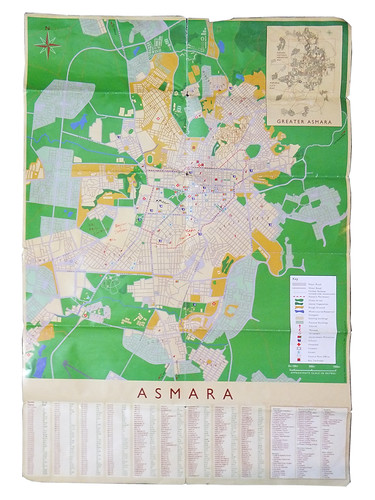

The back of the 2003 map.

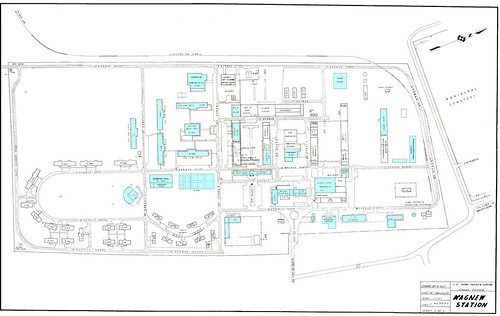

Former Kagnew station.

As the World Bank-financed CARP project shows, cartography has long been dominated by those in power: delineations, labels, emphasis, relations, detail, scale and many other factors are determined by political, military and economic forces. The fact that both maps I refer to have a sizable blank rectangle where American base Kagnew Station once was, is oddly telling.

A screenshot of the Kagnew Station map, available online, with interactive panels linking to photographs from within the base.

One might surmise that due to American military security, the roads and buildings within the fenced perimeter were off-limits to map makers. But the Americans left Kagnew Station in 1977, well before both maps; since then, the base has been reclaimed by Eritreans. Although the old exterior walls still stand, both the front and back gates were wide open when I was recently there – the area within is a dense urban community. Interestingly, former US soldiers stationed at Kagnew Station have created several detailed maps of their once exotic home, including a digital version that is interactively linked to photos posted on their website.

Concurrent to the time I spent in Asmara as a child in the late 1960s, at the height of the Cold War, another US military unit was explicitly charged with mapping Eritrea and its then-occupier Ethiopia. Called the Ethiopia-United States Mapping Mission, it had the ‘assigned mission of establishing geodetic control and collection of field classification data in Ethiopia to be used in future mapping programs.’ [1] The unit was headquartered in Addis Ababa and consisted of about 150 soldiers and their fleet of surveillance helicopters and airplanes. In 1965, foretelling future dissent, one of the unit’s helicopters was shot down by members of the Eritrean Liberation Front.

Maps haunt Eritrea to this day. The ongoing tensions with Ethiopia partially revolve around delineation of their shared border, with the town of Badme, in particular, a hotly contested prize.

The Asmaran ‘tank graveyard’.

For all its tourist-friendly detail, Denison and Ren’s map fails to mark one of the most fascinating monuments in all Asmara, itself related to mapping’s oldest tradition: the so-called ‘tank graveyard’. Easily a square-kilometer sprawl, this huge lot just west of old Kagnew Station is a teeming pile, sometimes four vehicles high, of rusty war detritus. Tanks, armored personnel carriers, trucks, cars, buses, plane parts, shipping containers, and more, are a testimony to Eritrea’s victory over Ethiopia in its war of independence. Most of the military equipment is Soviet-made, but I also found an Air Ethiopia Daimler-Benz shuttle, a US Army Ford Econoline van, numerous Land Rovers, the odd Fiat and stacks of Volkswagen Beetles and microbuses.

As Asmara tries to capitalise on one aspect of its colonial past – by mapping the Italian Modernist cinemas and other worthy buildings – Eritrea would do well to map its future: melt down the tank graveyard for farm equipment, cars, buses, bicycles and other useful designs.

All photographs by Steven McCarthy.

Read Steven McCarthy’s ‘Pride and posters in Eritrea’ on the Eye blog.

Steven McCarthy, Professor, University of Minnesota

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 84 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.