Tuesday, 7:00am

18 November 2014

Mirror mirror

What do the reflections in the images for Bowie’s new compilation tell us about his relationship with the audience? By Kevin J. Hunt

Seeing someone else’s reflection in a mirror is a curious, even disconcertingly uncanny, affair, writes Kevin J. Hunt.

A known face is easy to recognise, but details such as beauty spots, scars, the styling of hair and distinctively mismatched eyes, like David Bowie’s, are all reversed in terms of bilateral symmetry. Seeing Bowie staring back at you from the covers of Nothing Has Changed – The Very Best of Bowie is especially fascinating because so many of us feel we know him, or something of him.

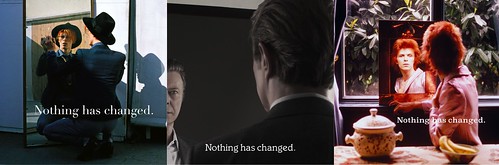

Looking into a mirror is one of the few ways to see both forwards and backwards at the same time. So it’s no coincidence that designer Jonathan Barnbrook’s choice of photographs for the three different cover designs of Nothing Has Changed – essentially a compilation / greatest hits album – play on this reflective motif.

As a pop icon whose career spans six decades (1960s-2010s), Bowie’s face carries a strong cultural resonance. His mismatched eyes punctuate an often coolly detached demeanour; his paralysed left pupil gives nothing away in its state of permanent dilation. The chosen images for Nothing Has Changed draw upon this cultural resonance to reflect Bowie – or at least three versions of him – looking back at us (over his shoulder) from significant moments in his career.

As ‘Ziggy’ in the early 1970s, we see Bowie seated at a table laden with bananas and a ceramic pot, gloriously androgynous in a pink suit. His left hand is clasped to his chest and neck in a knowingly effeminate parody of ‘vanity’, very much in keeping with the performer who shocked and amazed viewers of Top of the Pops in July 1972 with a famously ‘gender-bending’ performance of ‘Starman’.

1975 photograph by Steve Schapiro from the 2CD Edition / Digital Download version of David Bowie’s Nothing Has Changed.

Top: Mick Rock’s photo of Bowie at home in Beckenham, 1972. From the Double Vinyl version of the album.

We then see a version of Bowie from the mid-1970s, with trilby and glasses, around the time of playing eternal outsider ‘Thomas Jerome Newton’ in Nicolas Roeg’s film version of The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976). Writing on the surface of the mirror, like a scientist experimenting with formulas, we can recall the disillusioned alien attempting to both manipulate and communicate with the people around him, ostensibly for the profound good of them all.

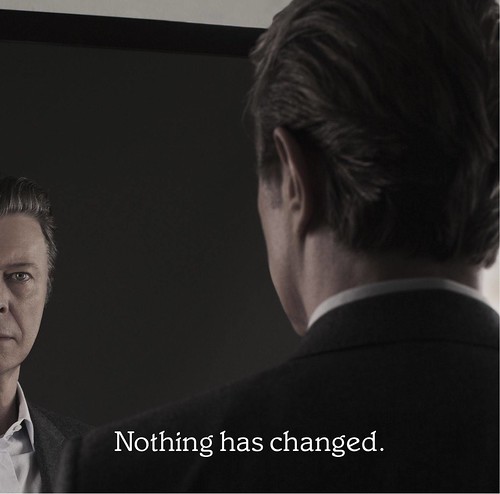

Photo: Jimmy King, 2013, from the 3CD Deluxe Edition / Digital Download version of David Bowie’s Nothing Has Changed.

Then we see a contemporary image in a grey suit, half drifting from view, suggestive of Bowie’s curious position as the outsider-turned-elder-statesman-of-rock and as a cultural influence worthy of entire galleries full of exposition and exploration – the Victoria & Albert Museum’s hugely successful ‘David Bowie is’ exhibition from 2013 continues to tour the world. (It is currently showing in the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, US, until 4 January 2015.)

Considered as a triptych (below), it is intriguing to see how Bowie’s reflection shifts in each photograph. From the near central position taken by Ziggy, framed by the mirror, to the slightly offset Bowie of the mid-1970s, through to the pared-down and only half-visible Bowie in the contemporary image.

In an interview for the NME, published in full on Bowie’s website, Barnbrook has suggested the cover designs are deliberately ‘undesigned’ – they aren’t overworked montages or full of fussy details. They are also ‘captioned’, rather than titled, with the seemingly paradoxical notion that ‘Nothing has changed’ encouraging the contemplative qualities of the photographs to show through. Barnbrook suggests interpretive possibilities, with Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891) offering a suitably Bowie-esque reference point for considering change over time.

What is clear is that these images are about perception rather than reflection. They are part of a dialogue with the viewer. Whether a fan or a critic of Bowie – and it is possible to be both – what each of us sees will always be shaped by what our own perceptions happen to represent, mirrors and their reflections included.

Kevin J. Hunt teaches at the School of Art and Design at Nottingham Trent University.

Video for the single ‘Sue (Or In A Season Of Crime)’, 2014, David Bowie’s collaboration with jazz composer Maria Schneider.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.