Monday, 9:51am

11 July 2011

Monopoly games

A handful of companies control online publishing, but what are the rules?

Design Week’s recent move from print to online-only might turn a profit in the short term, but the Web exposes publications to the whims of a few ruling monopolies, writes John Ridpath.

Publisher Centaur Media’s decision, which also saw New Media Age’s print offering disappear overnight, was part of a radical shake-up announced last month. On many levels, such changes are inevitable.

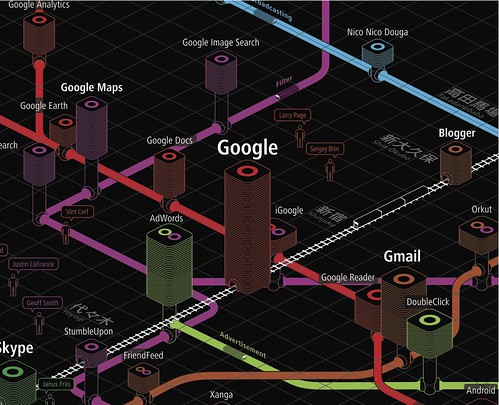

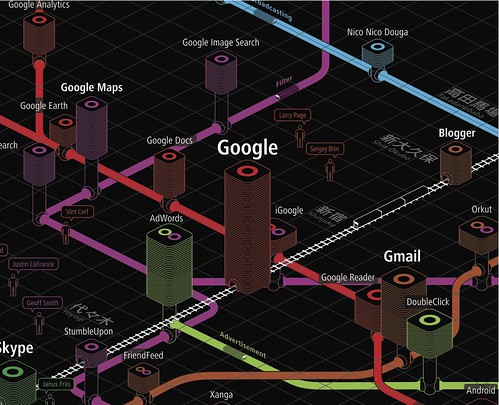

Top: Detail from Information Architects’ fourth Web Trend Map (2009), see ‘Undergrowth’ in Eye 78.

But a friend working at an online-only computer games magazine shared a cautionary tale about the perils of a Web-only publishing model.

In spring 2010, his publication’s audience unexpectedly dropped by two thirds: ‘It didn’t go down gradually, it was like a cliff edge.’ They managed to figure out that the drop was down to an update to Google’s search algorithm – somehow, they had gone down from page one of search results, to fifteen. Keen to hold on to more than 80 per cent of search engine marketshare, changes to Google’s winning formula are carefully guarded: ‘You can’t talk to Google directly about this’, says my contact, ‘there’s no line of communication.’ And when advertising revenue is linked directly to site traffic (and, more specifically, unique users per month), a drop of that magnitude is serious business.

Eventually, they worked out that the drop was down to changes in the way Google ranked websites based on page loading times. ‘Admittedly we had a slow loading site, and we managed to bring it from a few seconds to between 1 and 1.5. From then, we climbed back up to regular levels within a month.’ But this spring, the publication fell down the rankings again – this time thanks to the notorious ‘Panda Update’.

The changes were designed to penalise sites that Google’s algorithm designated as so-called ‘content farms’: a noble enough aim, but as a Guardian article pointed out, the losers also included a number of legitimate sites producing original content. For my friend’s magazine, there doesn’t appear to be an obvious route to recovery.

Above: Pentagram’s ‘brand architecture’ for Guitar Hero, 2009. See ‘We can be heroes’ on the Eye blog.

Site traffic to news websites doesn’t just come from search engines (though in the case of my friend’s publication it’s the largest chunk). According to the New York Times, site traffic to major news sites is increasingly coming from social networks, typically Facebook.

Yet publications are subject to the same vagaries here too. Facebook’s ‘News Feed’ selects the content you see according to mysterious algorithmic principles, and Twitter recently ditched their Design category, sparking the ire of Helvetica director Gary Hustwit (below). When we're dealing with the monopolies that control most internet traffic, it’s easy to see how arbitrary changes like this can have a huge impact on a publication's traffic and, ultimately, its revenue.

And what of the future? Well, Google and Facebook have signaled (with Google+ and a rumoured collaboration involving Microsoft’s Bing, respectively) that the Next Big Thing on the Web will be social search. In fact, it’s already starting to make its entry. I searched for a series of terms, once while signed into Google+ and once anonymously. Each time, the results differed significantly: when I was signed in, websites that my contacts had shared on social networks were highlighted – and were often placed higher in search results – than while searching anonymously.

This is all part of a wider trend towards ‘personalisation’ on the Web, which has been coming under scrutiny by Eli Pariser, author of The Filter Bubble: What the internet is hiding from you. As Pariser argued in his fascinating TED talk (below), the founding mythology of the internet promised that it could sweep away broadcasting society and the power of ‘editorial gatekeepers’. But with the personalised web, power has actually passed over to what Pariser refers to as ‘algorithmic gatekeepers’: ‘the thing is, the algorithms don’t yet have the kind of embedded ethics that the editors did’. If edited publications like Design Week are to survive online, they should always keep in mind the algorithms that are editing who actually reads them in the first place.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It’s available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop. For a taste of the current issue, see Eye before you buy on Issuu. Eye 80, Summer 2011, is on press.