Tuesday, 8:00am

7 July 2015

Posters of protest and peace

Lester Beall

Roman Cieślewicz

David Gentleman

Franz Grissler

István Grosz

El Lissitzky

Josh Macphee

Dmitry Moor

Alfons Mucha

Ferdinand Rubeš

Alois Hans Schramm

Ben Shahn

Elin O’Hara Slavick

Stenberg Brothers

Karl Sterrer

Paul Peter Piech

Alexander Rodchenko

Valerie Thai

František Zelenka

Design history

Graphic design

Posters

Reviews

The Poster in the Clash of Ideologies, 1914-2014

Edited by Jaroslav Andĕl.<br> Designed by Bedřich Vémola <br> Dox, Prague, 750 CZK.This Czech poster book contains much that is fresh and surprising, but makes some odd omissions. Review by Ken Garland

The context for the work shown in this book is usefully established by the 70 photographs that form its endpapers, writes Ken Garland.

They begin with images of protest marches at the outbreak of the First World War and end with posters opposing the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria. These are thoughtful and appropriate accompaniments to the main content: posters produced during the 100 years from 1914 to 2014. There is also a well placed and well considered text by the editor, Jaroslav Andĕl, the artistic director of the Dox Centre for Contemporary Art in Prague (also the book’s publisher).

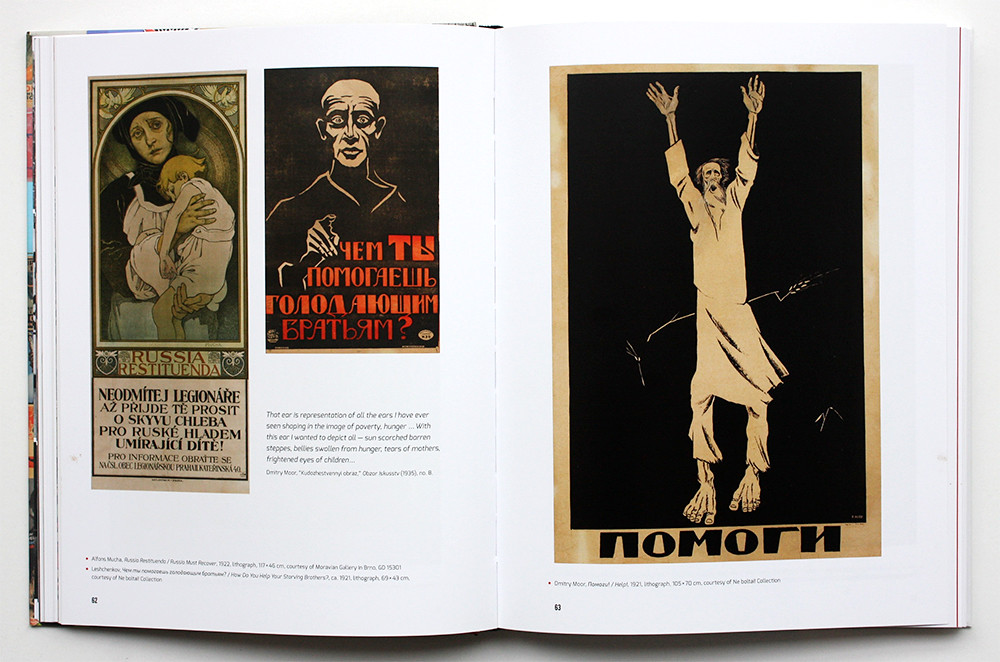

Alois Hans Schramm, ‘Subscribe to the Fifth Austrian War Loan’, 1916; Karl Sterrer, ‘Subscribe to the 8th War Loan’, 1917; Ferdinand Rubeš, ‘Subscribe for the Eighth Austrian War Loan’ ca. 1915; and Franz Grissler ‘Clothing Collection 1917’, 1917.

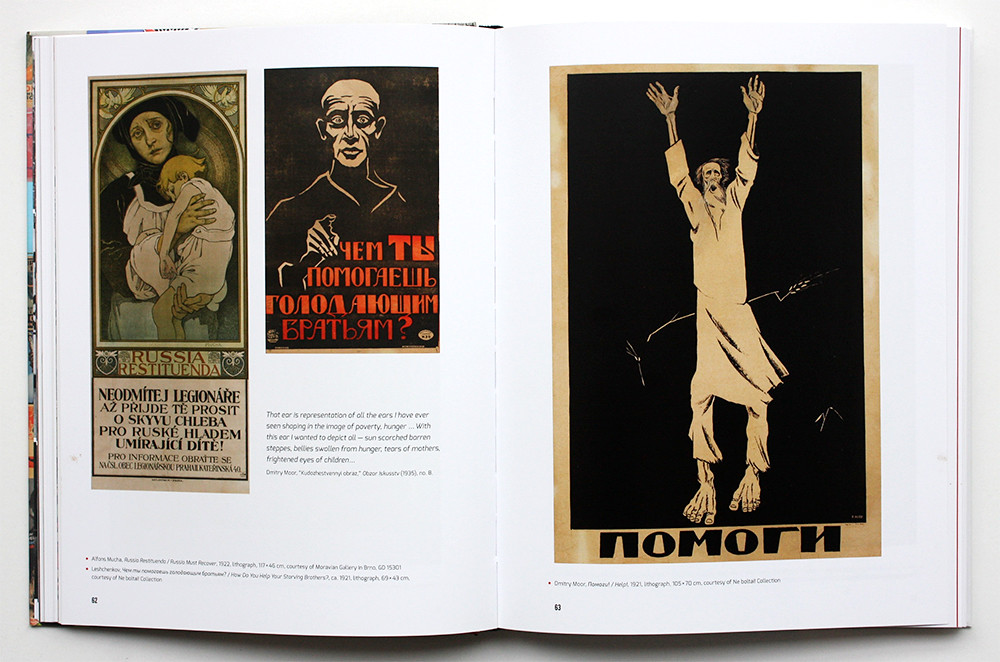

Top: Alfons Mucha, 1922, and Leshchenkov, ca. 1921. Dmitry Moor, ‘Help’, 1921 (right).

The book is the catalogue of an exhibition of the same name which ran at Dox from February to May 2014. This is not immediately apparent, as it is only referred to in small type on the last page. However, as the reader moves through the work, it becomes clear there is a decided emphasis on subject matter drawn from Czech and other Eastern European sources, mainly at Dox, the Ne Boltai Collection and the National Museum’s Modern Czech History Department, all in Prague, and the Moravian Gallery in Brno. Although these are buttressed by contributions from the Interference Archive and the Herb Lubalin Study Center of Design and Typography, both in New York, the bias is clear: Eastern European posters predominate over those from other nations, especially in the sections from 1989 that make up the latter half of the book.

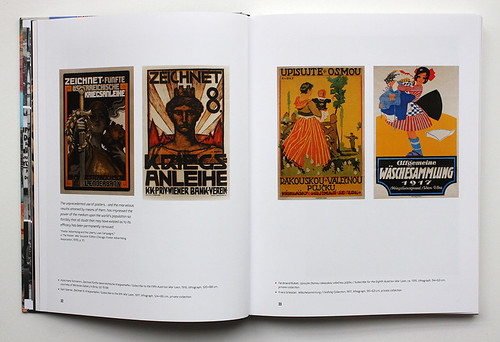

Anonymous designer, ‘An Exhibition of Legionnaire’s Work’ 1926; Ladislav Sutnar, ‘Exhibition of Modern Commerce’, 1929; and an El Lissitzsky poster for Kunstgewerbemuseum, 1929.

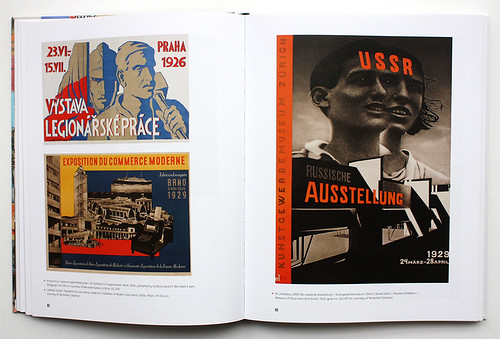

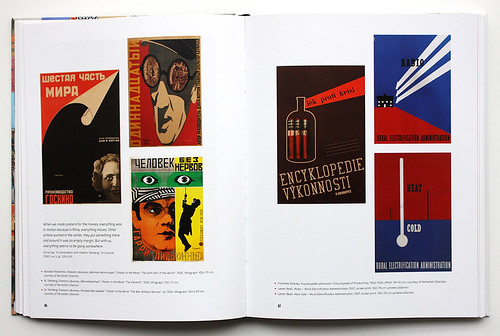

Alexander Rodchenko, 1926; Vladimir and Georgii Stenberg, 1928; Vladimir and Georgii Stenberg, ca. 1924; František Zelenka, 1932-34; and two posters designed by Lester Beall in 1937.

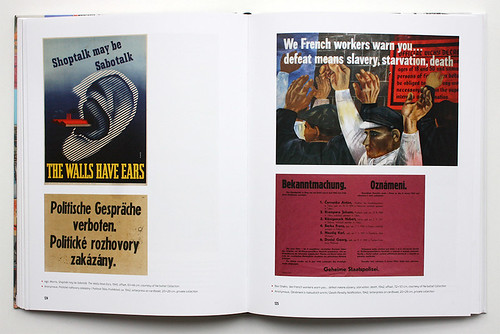

Morris, ‘Shoptalk may be Sabotalk’, 1945; anonymous designer, ‘Political Talks Prohibited’, ca. 1942; Ben Shahn: ‘We French workers...’, 1942; anonymous designer, 1942; and anonymous designer, ‘Death Penalty Notification’, 1942.

That said, it is intriguing how relatively under-represented Polish posters are, considering how prevalent they were between 1945 and 1989. There are some gestures toward Solidarność (the Polish trade union Solidarity), a couple of Roman Cieslewicz’s best and one Tadeusz Trepkowski, and that’s about it. Where, then, are Henryk Tomaszewski, Jan Lenica, Waldemar Swierzy, Wiktor Sadowski, Maciej Urbaniec and Andrzej Pagowski?

And strange, indeed, that none of the wonderful, anonymous posters produced by students at L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts during the Paris uprising of May 1968 is on view here – an especially odd omission as there is a tantilising glimpse of a whole wall-full of them in the endpapers.

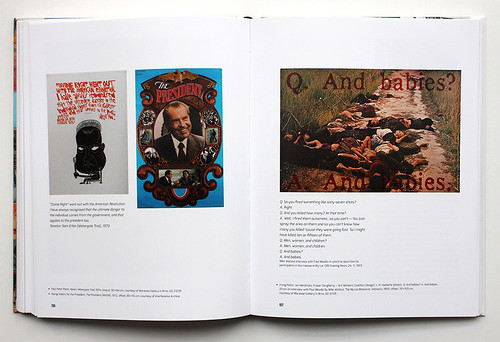

Paul Peter Peich, Nixon, Watergate Trial, 1974; Young Voters for the President, ‘The President’, 1972; and Art Workers’ Coalition: ‘Q: And babies? A: And babies’, 1969.

As for British designers, they are woefully neglected: no Abram Games, F. H. K. Henrion, Zero (Hans Schleger) or Tom Eckersley. And in the section ‘War on Terror, 2001-2008’, you would have expected at least one of David Gentleman’s splendid poster-banners for the anti-Iraq War protest marches. I may be prejudiced in this regard, but have to say that these omissions seem inexcusable.

To end on a good note: many of the illustrations are fresh and surprising, especially to a Western European eye. Though often naive and unskilled, they are a most welcome addition to the over-familiar array of old faithfuls that are the staple diet of anthologies of this kind. And the texts for the ten sections, written by seven authors in addition to the editor, are stimulating and informative.

This book, in spite of the above-mentioned shortcomings, is to be highly commended as a worthy record of what must have been a most memorable exhibition.

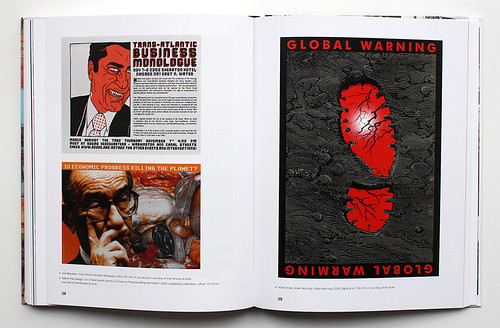

Josh Macphee, ‘Trans-Atlantic Business Monologue’, 2002; Valerie Thai and Elin O’Hara Slavick, ‘Is Economic Progress Killing the Planet?’, 2000; and István Grosz, ‘Global Warning. Global Warming’, 2006.

Ken Garland, designer, photographer, London

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.