Wednesday, 3:25pm

4 January 2012

Savagery beneath the skin

Ronald Searle, British illustrator,

3 March 1920 to 30 December 2011

Everyone has a way into the work of Ronald Searle, writes Derek Brazell, whether it’s through the devastating visual critiques of his political cartoons for French newspaper Le Monde through the 1990s and 2000s, or the wicked humour that bursts from the dangerous-to-know schoolgirls of St Trinian’s.

His empathetic magazine reportage encompassed abandoned refugee camps in the late 1950s and comically observed life in West Coast USA – presenting human existence in many forms, from the miserable and haunted to the privileged and smug.

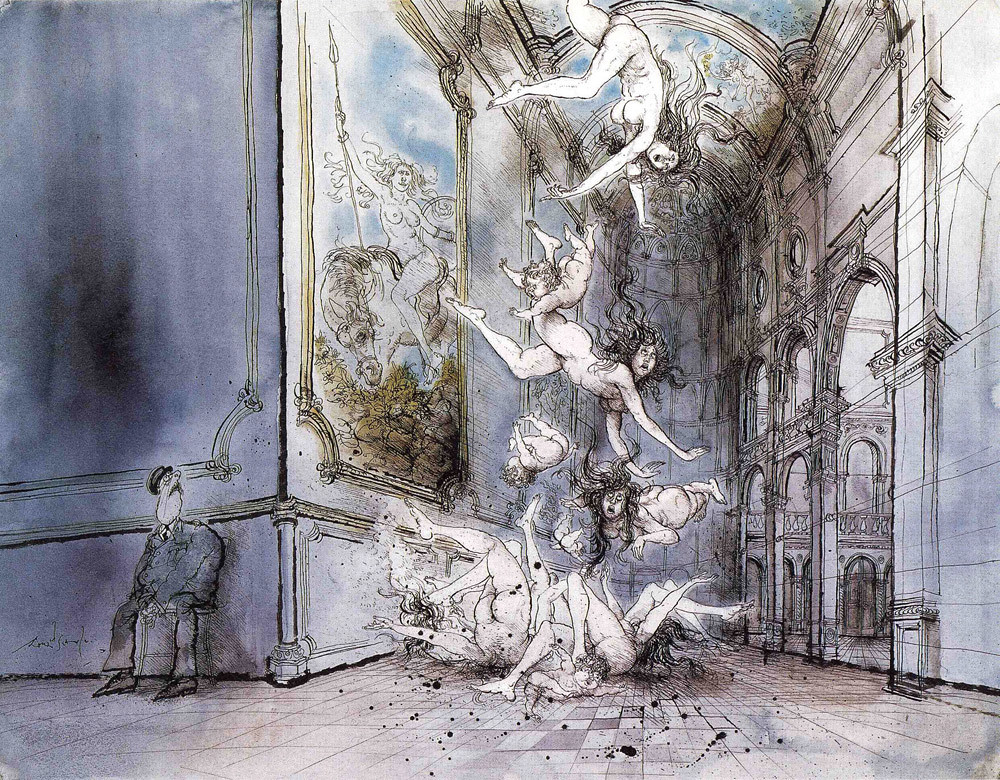

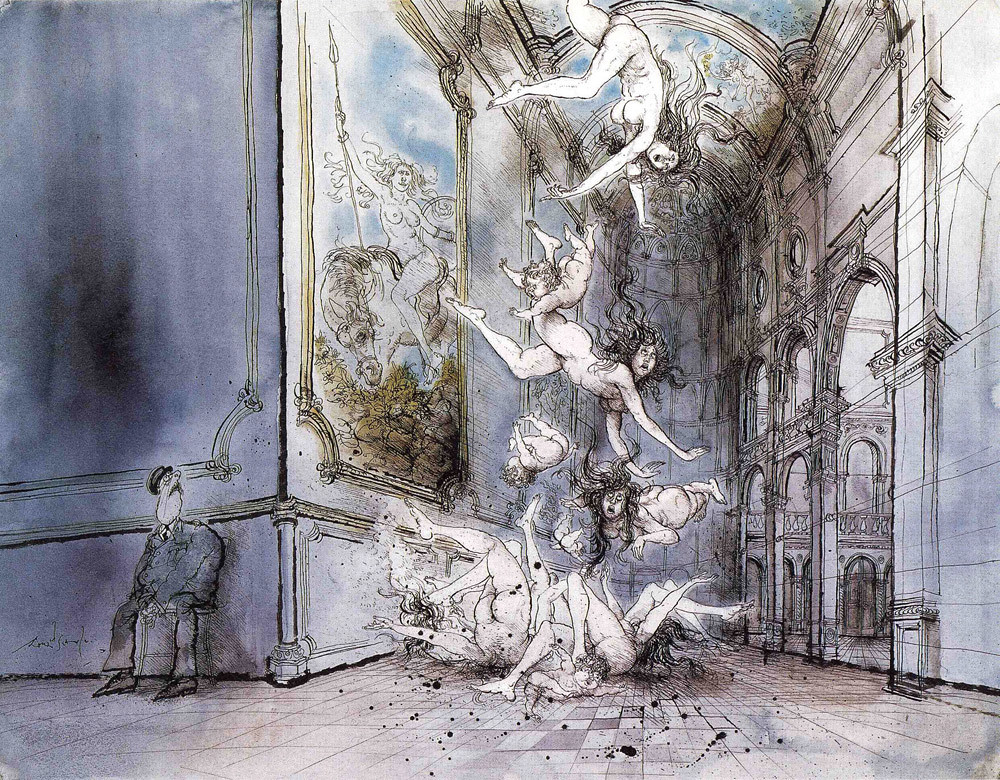

Top: Al Fresco, 1977. Collection of Ronald and Monica Searle.

Below: ‘Mercenaries’, Le Monde 1990s.

All with acute observation. ‘Any artist interested in people – and you have to be interested in people – immediately you can diagnose the nuances,’ he said of his ability to reveal character.

Born in 1920 in Cambridge, Searle drew from when he was a young child, and by fifteen was doing a weekly cartoon for the Cambridge Daily News. He was called up for duty in 1939, and captured by the Japanese in 1942, enduring three years of imprisonment and hard labour.

Below: Cholera Lines, 1943.

But throughout it all he drew. The Imperial War Museum holds a collection of Searle’s drawings, and the images from his internment as a prisoner of war hold a striking immediacy whether or not you are aware of the life-threatening conditions they were created in. He would hide his drawings under the bodies of cholera victims, as the guards were too afraid of the disease to search there.

I asked him if commenting on some of the worst aspects of human behaviour for Le Monde made him cynical. ‘Having had a certain amount of experience of savagery, there’s no real problem for me to try and interpret it into edible lines, if you like. Cynical? No, I don’t think so. There’s a certain sort of resignation that, whatever the veneer, the savagery is just below the skin, in any country.’

Searle’s career flourished after the Second World War, with work across editorial, book publishing, film and advertising. He became well known for rather formless furry cats and shaggy dogs, which were all really stand-ins for human beings.

Below: ‘Totem in Ketchikan, Alaska’, Holiday, 1962.

Talking to him in 2010, he was sharp, still watching the world, but aware of his age. ‘The thing which is awful is the head is clear, and there’s this ghastly business of the body letting you down. That you can’t escape from…’

Above: ‘Taxi, Georgia’, Punch, 1959.

Many of the Searle obituaries hold up the St Trinian’s cartoons and Molesworth book illustrations as his most recognisable. While this may be true, he would have possibly been less than thrilled that this was his immediate legacy. ‘I killed them off in the 50s!’ he exclaimed about those pesky schoolgirls. Anyone investigating a little further will be rewarded with an astounding body of work from one of the greatest commercial artists the UK has produced, with an influence that will endure.

Photographs (above and below) by Andrea Liggins.

Thanks to Wilhelm-Busch Deutsches Musuem für Karikatur & Zeighenkunst, Hanover (which has an archive of 2200 of Searle’s works on permanent loan); London's Cartoon Museum and Imperial War Museum, London for images.

All artwork copyright Ronald Searle estate.

See Derek’s article about interviewing Ronald Searle for Making Great Illustration by Derek Brazell & Jo Davies (A&C Black, 2011), to be reviewed in Eye 82.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It’s available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue, Eye 81.