Wednesday, 9:00am

3 January 2018

The accidental student

What happens when you have just minutes to come up with a design? John Ridpath writes about the problem-solving benefits of ‘creative accidents’

‘Look at the photocopied type specimens on the table. Pick a letter “A” that you like. Draw a copy of it anywhere on your sheet of paper, using charcoal. It can be big or small, you can rotate it, you can draw it partially off the page. You have five minutes.’ Rod Judkins has just issued the first brief of ‘100 Design Projects’, a five-day course at Central Saint Martins, writes John Ridpath.

Immediately, the questions begin: ‘Should I draw it in the middle?’ ‘Do I need to leave room on the page?’ Judkins simply repeats the brief, leaving the attendees – a motley crew of students, professionals and retirees – to figure it out for themselves.

Five minutes pass, and without a moment to spare we receive our next instruction. ‘Now pick an “S” that you like, and add it to the page.’ People are visibly upset by this disruptive and unexpected instruction. I attempt to rescue my careful composition, and just as I find space for my ‘S’ to fit, we are forced to add an ‘H’, then a ‘C’, then an ‘O’.

Pinning our work to the wall for a group review, no-one seems particularly pleased with their own creation. However, we all have plenty of positive things to say about each other’s work. Interesting things happen when you work at speed and make mistakes – in fact, the mistakes seem to be the best bit. It’s then that we realise our creations spell out ‘CHAOS’.

‘Draw letters A [then S, H, C, O].’

Top: The remains of a 1993 copy of New Statesman, after a challenge to come up with ten characters for a story.

Subsequent design briefs ask us to create: ‘a complete typeface using only two geometric shapes’; ‘a piece of jewellery for Kim Jong-un’; ‘a family crest for Mark Zuckerberg’; ‘a flag for cyberspace’; ‘a new symbol for infinity’; ‘an advert for deep fried peanut sandwiches’; and ‘a literacy poster for adults that can’t read.’

With only about ten or fifteen minutes to work on each one, everyone grabs whatever materials come to hand, improvising with charcoal sketches, messy paintings, ink-splattered cardboard models, scrappy collages and street photography.

‘Create a piece of jewellery for Kim Jong-un.’

‘Design a literacy poster for adults that can’t read.’

After a few weeks of recovery, I met with Judkins to find out more about the origins of the course and his latest book, Ideas Are Your Only Currency (Hodder & Stoughton, £9.99).

‘It all began on the degree course,’ he said. ‘We’d set the students two-week projects, and they wouldn’t do any work until the day before. So we started setting them quick projects instead. We really liked what they produced, and the students asked for more.’

Judkins noticed that working this way forced students to take a more creative approach. ‘Let’s say you set a brief to design a chair. On a traditional project, students start doing research – maybe they head to the V&A to look at other chairs. From this research, they create ideas. Finally, they pick the idea they find most interesting.’

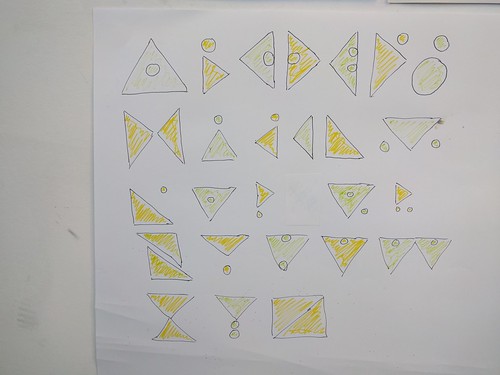

‘Create a complete typeface using only two geometric shapes.’

With only fifteen minutes to design a chair, you can’t go to the V&A. There’s barely time to Google. You have to come up with your own idea. Working in this way, Judkins has noticed that students become more fluent with ideas: ‘If something’s not working, they just think of a totally new idea. Often these ideas are the most creative’.

And when it comes to execution, there’s no time to turn to InDesign or Sketch. ‘I’m not anti-computer’, says Judkins, ‘but unless you’re a programmer, everything feels pre-planned – it’s harder to have an accident’.

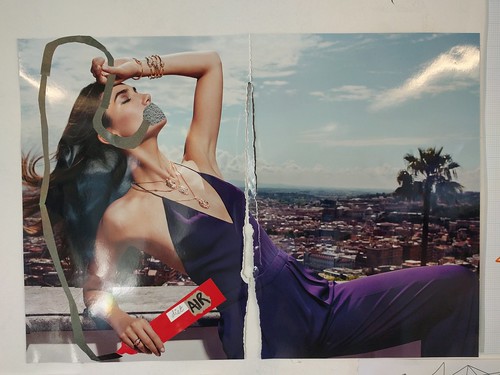

‘Design packaging for air.’

While I have always known that constraints – specifically tight briefs and time limits – can ease the path to ideas, ‘100 Design Projects’ helped me realise how powerful diverse analogue materials can be in the creative process. Day four began with a quick look at some Tom Gauld illustrations for inspiration, then the brief: ‘create ten characters for a story; you have fifteen minutes’. While everyone else quickly buried their heads and began illustrating, I drew a complete blank. After ten minutes of despair, I started wandering around the room on the hunt for inspiration. Flicking through a pile of magazines, I discovered a yellowing copy of the New Statesman from 1993. Frantically, I began cutting out names and heads and jumbling them all up.

Ten characters, created from the pages of a 1993 issue of New Statesman.

I ended up with a cast including: ‘Crack Magic’, ‘The Talented Mr Waldegrave’, ‘Skin sisters’, ‘Anorak Killers’, ‘Pie Finger’, ‘Sarah Baxter’ and ‘A Lovely Man’. Suddenly energised and brimming with ideas, I went home and spent the evening writing it all up as a short story. For someone plagued with writer’s block, it was a hugely powerful moment.

Perhaps that explains why Judkins has increasingly found himself working with people outside of the visual arts – such as a group of UCL medical students. ‘Doctors are problem-solvers,’ he explains. ‘Every day they are faced with problems they haven’t been taught about. One surgeon explained “we want our students not just to know what they were taught, but to think about how they could do it better”.’

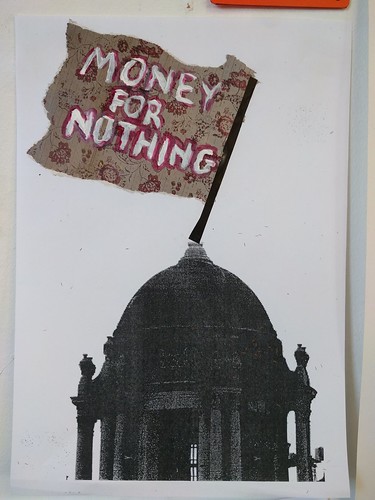

‘Design a new statue for the top of the Bank of England.’

Setting briefs to design an artificial liver or a deadly virus, Judkins forces them to look at things differently. ‘At first, medical students find it more disconcerting than art students – but they still get there. Qualified doctors are already a creative bunch. The burns department at the Royal Free [Hospital in London] came up with an incredible spray-on skin, and surgeons take sculpture classes to better understand the human body.’

Judkins argues that a huge number of history’s most significant scientific discoveries happened by accident. ‘I’d go further,’ he adds, ‘and say that scientists deliberately create accidents.’

At the heart of his vision is the idea that creativity is the most important part of any discipline. And the recipe for success might be simpler than anyone might think – the art of the intentional accident.

John Ridpath, Head of Product, Decoded, London

‘Create an outdoor memorial.’

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.