Monday, 4:30am

7 January 2013

The power of chess

various designers

Josef Hartwig

Marcel Duchamp

Patricia Lindsay

Studio Frith

Paul Smith

Design history

Graphic design

Posters

Visual culture

Chess – the gymnasium of the mind – is a perennial source of inspiration for designers, film-makers and artists, says Jim Sutherland

It’s no wonder chess holds such a fascination for artists, film-makers and designers, writes Jim Sutherland. It has such a rich visual language to plunder.

There are 32 pieces with six different characters that are loaded with iconography – kings, queens, bishops, knights, rooks and pawns in a strict hierarchy. There’s a square, black-and-white grid: myriad possibilities are played out in a confined space.

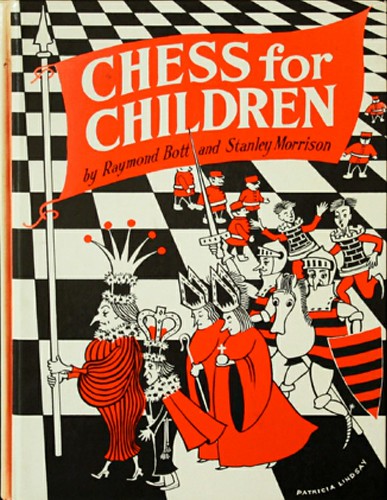

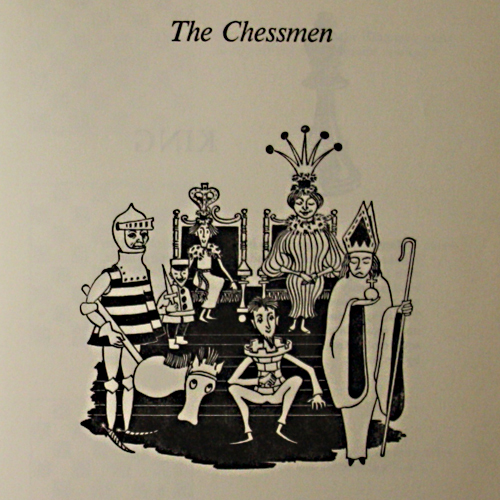

Cover of Chess for Children (Collins, 1958).

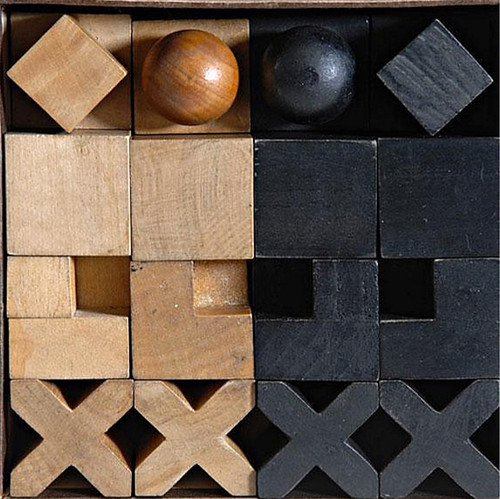

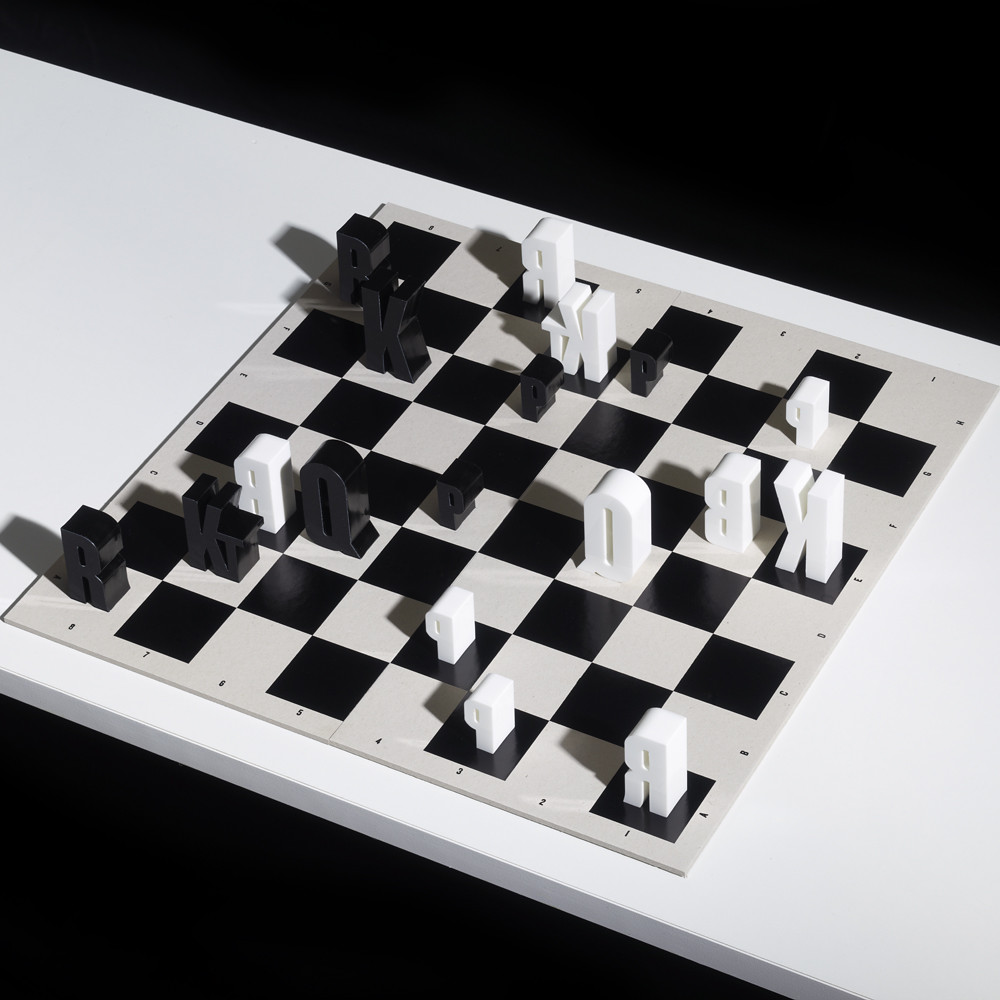

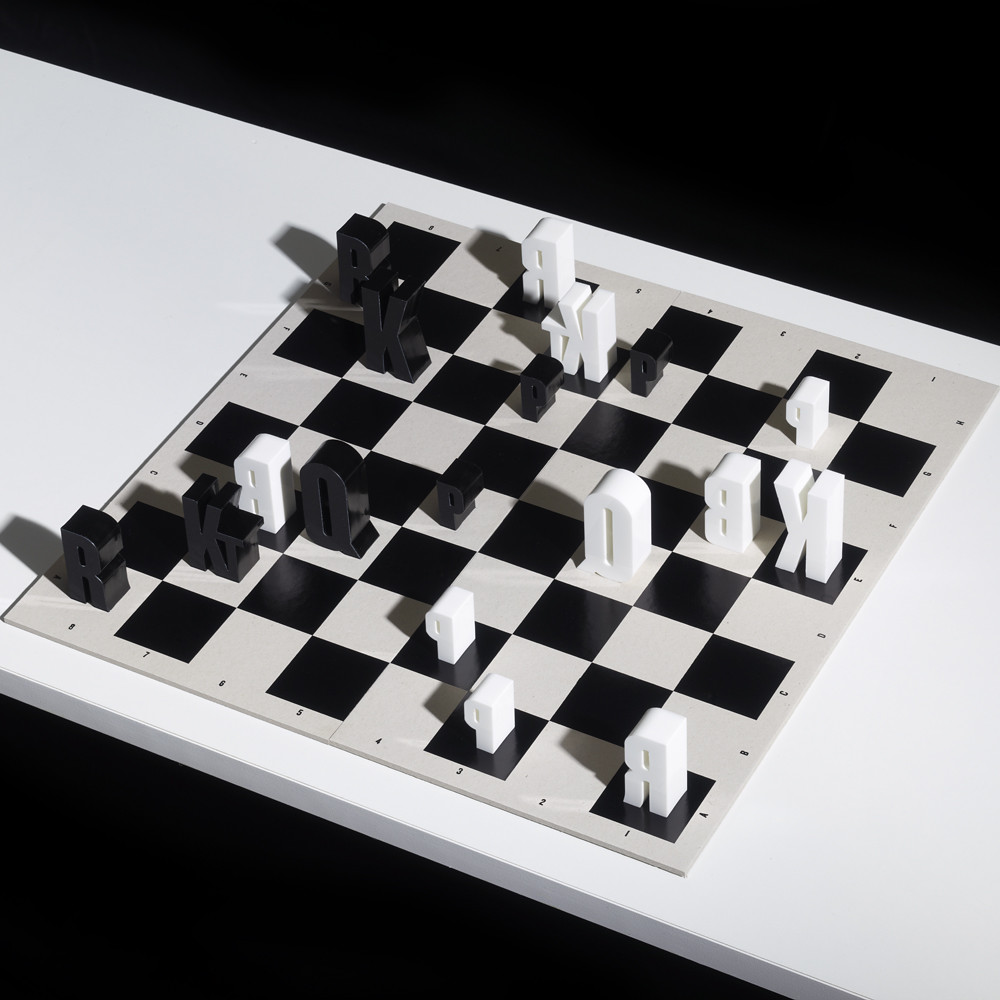

Top: typographic acrylic chess set designed by author Jim Sutherland, 2012.

My first chess book was Chess for Children (above). I remember how the small black and white illustrations brought the characters to life: a powerful queen and a slightly pathetic king. It struck me as a secret world that was impossible to comprehend yet I was intrigued enough to try. For all the complexity, it boiled down to something simple: a one-on-one war of wills.

Then came the exotic-sounding names and personal battles between champion players to spark the imagination: Garry Kasparov versus Anatoly Karpov (Kasparov became the World Chess Champion in 1985 at age 22) and Bobby Fischer versus Boris Spassky (subject of a 2008 documentary film Bobby Fischer Against the World). The game also has an expressive lexicon of opening moves – King’s Indian Attack, The Sicilian Defence, The Bullfrog Gambit.

My early enthusiasm has stayed with me, inspiring a number of chess-related projects over the years including – a board, some letterpress posters and an outdoor set – all personal explorations around the language of chess. Most recently, I designed a typographic set (top), which brings together two of my long-held interests.

As part of my research, I came across many lovely examples of thinking around the game.

Chess set by Josef Hartwig from 1924, featured in the 2012 Bauhaus exhibition at the Barbican, London.

See Alex Cameron’s ‘Modern games’ on the Eye blog).

A wonderfully compact example from MoMA designed in 1966 by F. Lanier Graham. The pieces form a perfect cuboid in the box.

A really intelligent, sustainable Chess Set by Matthew Livaudais made from matching laser-cut plywood.

Cloth ‘board’ by Studio Frith, 2012.

Chess features frequently in modern art, seen recently in the travelling exhibition ‘The Art of Chess’ at the Saatchi Gallery, which featured work by Yayoi Kusama, Damien Hirst and Rachel Whiteread, and ‘Games’ at Gallery Libby Sellers in London, which included work by Fabien Cappello, Studio Frith and Julia Lohmann.

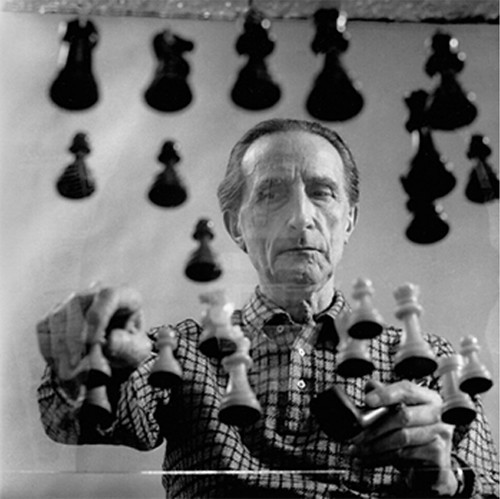

‘Games’ was inspired by a 1944 exhibition at New York’s Julien Levy Gallery for which Levy, Max Ernst and Marcel Duchamp (below) invited artists to contribute chess sets, art works and furniture. (Duchamp famously ‘gave up art’ to devote his life to chess.)

Marcel Duchamp. Photograph by Arnold T. Rosenberg, 1958.

The game featured in ‘The King stay the King’ episode of the TV series The Wire (season 1) where D’Angelo explains the rules of chess to his crew. The King is the drug lord and the dealers are the pawns.

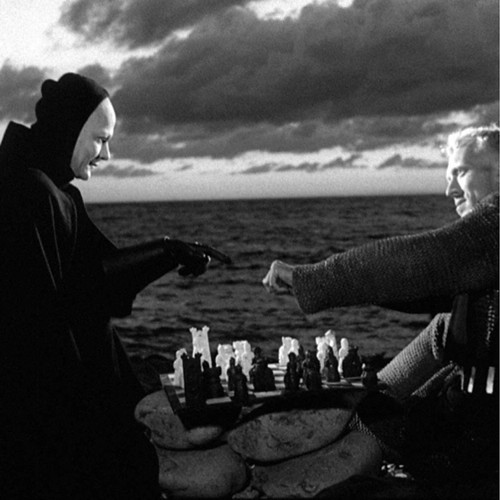

The game has appeared in many films and television series – most famously in The Seventh Seal (Ingmar Bergman, 1957, below), where a knight plays Death at chess in order to distract him.

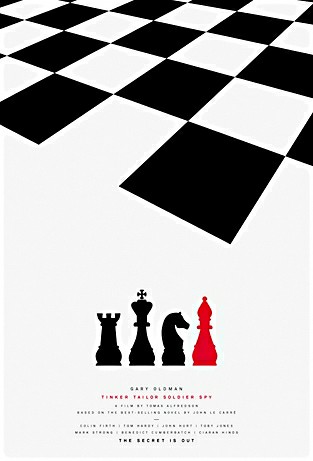

Chess is found in literature, from Alice as a pawn in Through the Looking-Glass to Tinker, Tailor, Soldier Spy where each suspect is assigned a chess piece. This led to a great Paul Smith poster (below) for the recent film adaptation.

While I am not a good player, I do enjoy losing myself in thought while contemplating the next move.

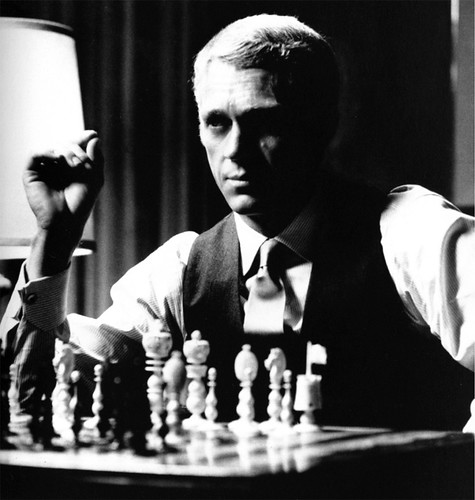

Steve McQueen in The Thomas Crown Affair (1968).

Illustration by Patricia Lindsay from Chess for Children, 1958.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 84 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.