Wednesday, 9:30am

24 January 2018

The visual language of Pooh

Winnie-the-Pooh: Exploring a Classic

Victoria & Albert Museum, London, 9 December 2017 – 8 April 2018<br> Co-curated by Emma Laws and Annemarie Bilclough<br> Exhibition design: Tom Piper and RFK Architects<br>Winnie-the-Pooh, Exploring a Classic: The World of A.A. Milne and E.H. Shepard

By Annemarie Bilclough and Emma Laws<br> V&A Publishing, £30<br>

One of most charming and clever aspects of the Christopher Robin books (by A. A. Milne and illustrator E. H. Shepard) is that they can be read on a number of levels, making them equally enjoyable for both children and adults, writes Clare Walters.

This interactive multi-sensory exhibition at the V&A aims for a double-layered appeal similar to that of the original books: When We Were Very Young (1924), Winnie-the-Pooh (1926), Now We Are Six (1927) and The House at Pooh Corner (1928). A first for the London museum, ‘Winnie-the-Pooh: Exploring a Classic’ is designed for families, with a multitude of play opportunities for children as well as intriguing historical material for adults.

Installation images of ‘Winnie-the-Pooh: Exploring a Classic’ © Victoria and Albert Museum.

Top: Line block print, hand coloured by E. H. Shepard, 1970 © Egmont, reproduced with permission from the Shepard Trust.

At the centre of the exhibition is a beautifully recreated, life-size section of Hundred Acre Wood. Here, children can discover the Bee Tree and walk over a model of the famous Poohsticks bridge, based on the real-life Posingford Bridge in Ashdown Forest. They can also watch the ‘stream’ that runs underneath, in which leaves, sticks and words apparently whirl in a watery current of sparkling light. Surrounding them are the sounds of the forest, including water splashing, birdsong and buzzing bees, creating the feel of a warm summer’s day in the country. Altogether the show is a thoroughly immersive and joyful experience.

Other life-sized scenes include a staircase, referencing the poem ‘Halfway Down’; a nursery bed on which children can actually lie, based on the one in Christopher Milne’s nursery in Mallord Street; fake tree trunks and logs for sitting on and hiding in, and little doors to open and explore. There are also dressing-up clothes, a drawing table and interactive games for children to play, as well as a cosy ‘cave’ in which to curl up and listen to extracts from the books or read the words projected onto the ceiling.

Installation image of the life-sized staircase in ‘Winnie-the-Pooh: Exploring a Classic’ © Victoria and Albert Museum.

Milne’s words in this exhibition have a solid physical presence. They appear written on the walls and floors, moving, swirling and breaking up in the ‘stream’, running in heavy black lines like driving ‘rain’ across a window, and hanging from the ceiling in a giant white mobile of Pooh’s special Outdoor Song ‘The more it SNOWS-tiddely-pom’. This reflects the tight interplay between the visual and the verbal in the books. Milne and Shepard worked closely together to achieve this harmony, writing and meeting frequently, and often working with the publishers ‘to arrange the make-up’ of the text and illustrations on the page. This complement of words and images can be seen in the Winnie-the-Pooh illustration where Pooh climbs up the Bee Tree on the left and the text, arranged vertically to mirror the tree, reads down on the right.

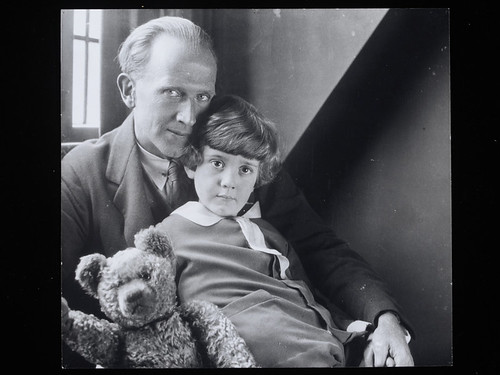

A. A. Milne, Christopher Robin Milne and Pooh Bear, by Howard Coster, 1926. © National Portrait Gallery.

As well as family photo albums, a number of Milne’s manuscripts are on display, on loan from the Wren Library, Trinity College, Cambridge. Written in small neat handwriting, they show how Milne thought about the way the words might be placed on the page. On one page he wrote, ‘If this is flying I shall never really take to it’ in a ‘bumpy’ style that reflects the bumpy ride Piglet is experiencing. This visual use of language helps the storyteller to read the book out loud and turns it into more of a ‘live’ performance. Milne’s skills as a writer, and the linguistic techniques he employed – such as his use of rhythm, assonance and alliteration, repetition, capitalisation and sound effects – are excellently described by Emma Laws in the catalogue Winnie-the-Pooh, Exploring a Classic.

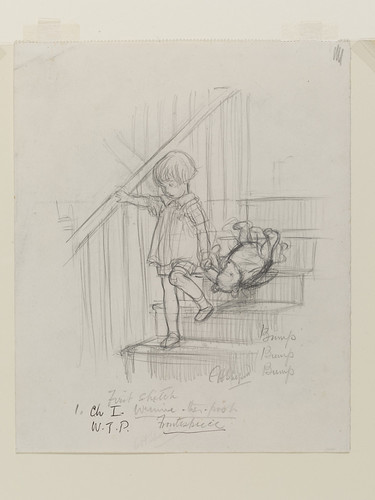

The real stars of the exhibition, though, are Shepard’s drawings. The V&A has the largest collection of his Winnie-the-Pooh pencil drawings in the world, and these are on display for the first time in 40 years. Shepard often worked from life, drawing both the landscapes of Ashdown Forest and Christopher Milne’s actual toys, which were the inspiration for the characters of Pooh, Piglet, Eeyore, Kanga and Tigger (though Pooh actually looked more like Shepard’s son’s teddy bear Growler, and Owl and Rabbit were Milne’s own inventions). Shepard’s depiction of the forest in different seasons and in a range of weathers, from snowy to misty to ‘Blusterous’, adds depth to the Winne-the-Pooh books, giving them a powerful sense of place. In Winnie-the-Pooh, Exploring a Classic, Annemarie Bilclough analyses the methods Shepard used to create his drawings, including his use of different tools and materials, his inclusion of playful details, his ability to represent movement and sound, and his method of ‘decoding’ the text for younger readers so that they realise what is happening moments before the characters do.

‘Bump, bump, bump’, Winnie-the-Pooh chapter 1, pencil drawing by E. H. Shephard, 1926. © The Shepard Trust, reproduced with permission from Curtis Brown.

The final section of the exhibition focuses on the production methods used to create the books. It shows how Shepard’s pencil sketches were turned first into pen drawings and subsequently into relief line blocks (a couple of these are on display) that could be set alongside the letterpress text to be printed simultaneously. One sequence in this section shows the development of the cover of The Christopher Robin Story Book (1965) with the image transforming from a rough pencil sketch, to a sharper coloured-in sketch, to the finished illustration, to the actual cover. Beside this is an interactive screen that shows the magazines in which many of the poems and stories first appeared, including the first ever drawing of Winnie-the-Pooh (as a named character rather than as an anonymous teddy bear), by the Punch artist J. H. Dowd, which was printed in The Evening News on 24 December 1925.

The four Christopher Robin books have now been translated into more than 30 languages and have inspired an enormous range of spin-offs, from toys and games to clothing and homewares. The visually familiar settings, situations and characters of the poems and stories have also been the subject of many parodies – some appearing almost as soon as the originals were published – and have been used as the basis for satirical and political cartoons.

Those who remember Milne’s work from their own childhood will almost certainly enjoy ‘Winnie-the-Pooh: Exploring a Classic’, while younger ones who have yet to discover Pooh will have a chance to meet him and his friends for the first time. However, if you are going with young children and want more than a superficial glance at the exhibits, head there with two adults rather than one. That way you might each get a chance to quietly discover the fascinating history behind ‘The best bear in all the world’.

* For more information, see: https://www.vam.ac.uk/winniethepooh

** The V&A Museum of Childhood in Bethnal Green is hosting a complementary display of teddy bears to coincide with the exhibition

Note: A shorter version of this review will appear in the Children’s Books History Society Newsletter.

Installation image of ‘Winnie-the-Pooh: Exploring a Classic’ © Victoria and Albert Museum.

Clare Walters, writer, author of children’s picturebooks, London

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.