Friday, 8:00am

12 September 2008

Up against the wall

The Poster-Film Collective. Beyond the designer-client relationship

The Summer 2008 issue of Eye, no. 68, went ‘Beyond the canon’ to question and to enlarge the accepted pantheon of graphic design; here, designer Andrew Howard draws attention to the History Sets of posters produced by the Poster-Film Collective.

The business of graphic design is usually expressed as a commercial exchange between client and designer – a social relation of demand and service, of commission and execution. Graphic communication outside that exchange is often viewed as if it belongs to another activity, and not subject to the ‘neutrality’ of professional practice.

Yet there are plenty of examples of powerful work made in the pursuit of political as well as social objectives – Soviet posters of the 1920s, later Cuban and Polish posters, the anti-war and anti-bomb graphics of the 1960s, the French street posters of the Atelier Populaire. Such examples are unquestionably graphic design, yet they are often sidelined as ‘propaganda’. Considering that most advertising is a form of propaganda, the distinction is not helpful.

If we are to avoid a history of design that is reduced to a history of visual forms, that history must contain an account of the ways in which content is produced and reproduced. Things look the way they do not simply as a result of individual choice but because of the collaborations and negotiations involved in their conception, the methods of production available, the materials at hand and the objectives that they were designed to pursue. Graphic forms and solutions are not empty vessels; they reflect their content – look at any commercial ad.

The Poster-Film Collective was formed in the early 1970s by a group of artists, photographers and filmmakers – mostly former staff and students from the London art colleges – with the aim of addressing political issues in a coherent visual style using forms of reproduction easily available to them. During the 1970s and 80s they produced posters and films, and organised exhibitions in collaboration with trade unions, community groups and women’s organisations, among others.

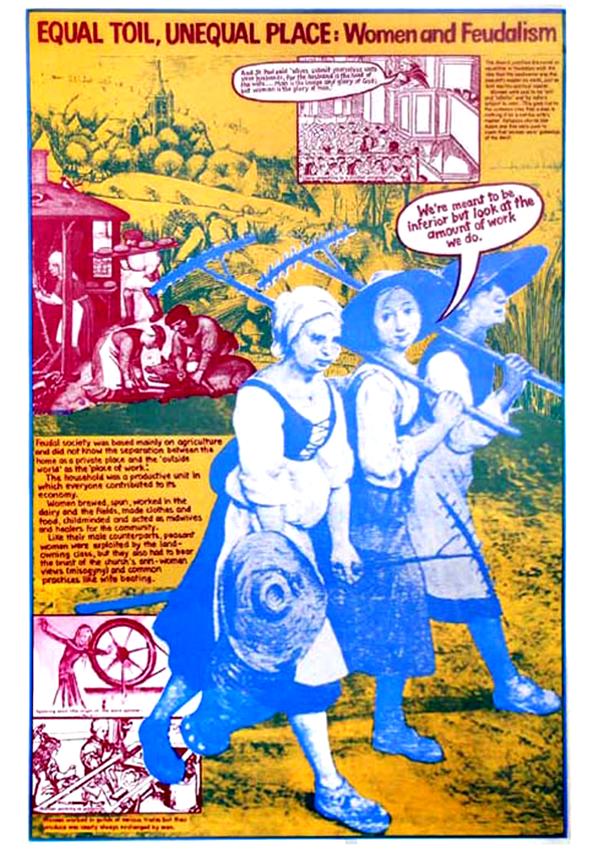

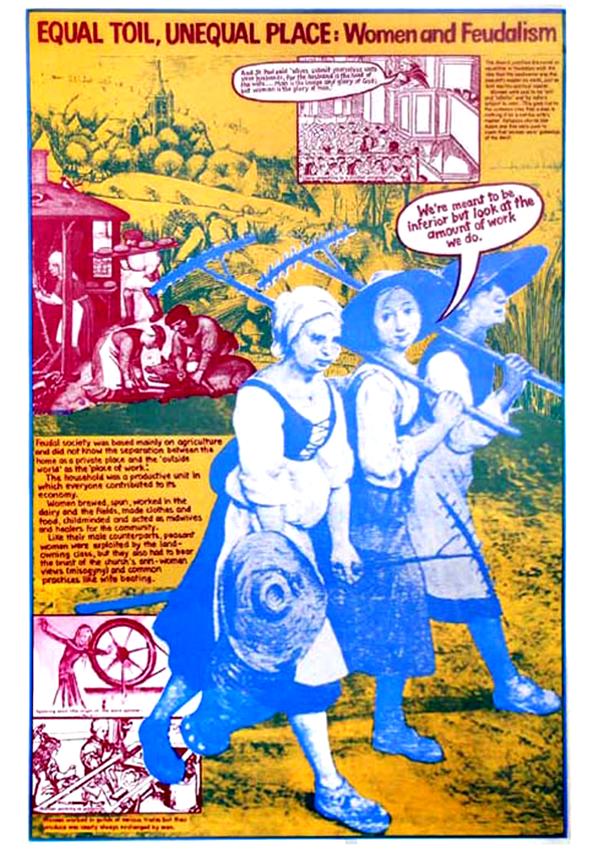

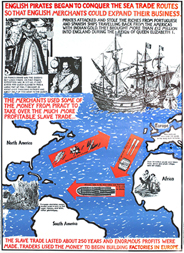

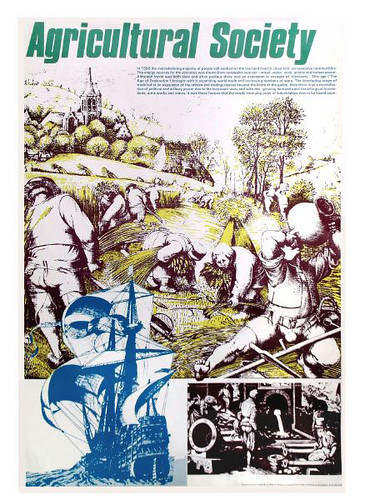

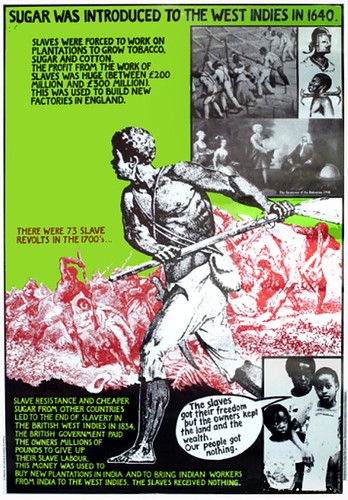

Particularly striking are the educational posters called the History Sets – three sets of twelve posters that depict the interlocking histories of colonialism, technology and women’s history.

These were conceived and assembled using hand-drawn text and collage, and the resulting aesthetic suggested immediacy and methods of production within the reach and control of the group and hence available to others – though only the first run of the first set was hand-printed. Set two was silkscreened commercially and set three was produced by litho process.

The posters were sold at demonstrations, meetings and conferences, and by labour and women’s groups, as well as bookshops. The ‘Whose World Is the World’ set (History of Colonialism), made in collaboration with teachers, was distributed through (the now defunct) Inner London Education Authority and by mail order to schools.

The History Sets are a notable example of graphic communication that lies beyond the perimeter of orthodox professional practice but reflects an energy and sense of purpose often lacking in our everyday graphic culture.

Poster-Film collective website: poster-collective.org.uk

Other articles by Andrew Howard include: ‘There is such a thing as society’ (Eye no. 13 vol. 4) and ‘Design beyond commodification’ (Eye no. 38 vol. 10).

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.