Wednesday, 11:15am

28 February 2018

Words and the natural world

The Lost Words: A Spell Book

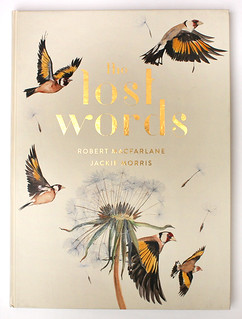

By Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris. Book Design: Alison O’Toole. Hamish Hamilton, £20<br>The Lost Words

The Foundling Museum, 40 Brunswick Square, London WC1N 1AZ<br> 19 January–6 May 2018, Free<br>The Lost Words, an enchanting book and exhibition by Macfarlane and Morris, celebrates entries (including ‘ivy’ and ‘conker’) that were dropped from the Oxford Junior Dictionary

Every now and again there is a publishing phenomenon – a book that stirs the soul and captures the public imagination. The Lost Words: A Spell Book by Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris is one such phenomenon, writes Clare Walters.

It aims to ‘re-conjure’ the nature words that we have lost from our everyday vocabulary, and from the moment of its publication in October 2017 it was a runaway success. It has not only received widespread critical acclaim and is a Sunday Times top ten bestseller, but it has also shipped over 75,000 copies, been sold into North America, and is currently being translated into German. Not bad for the first three months.

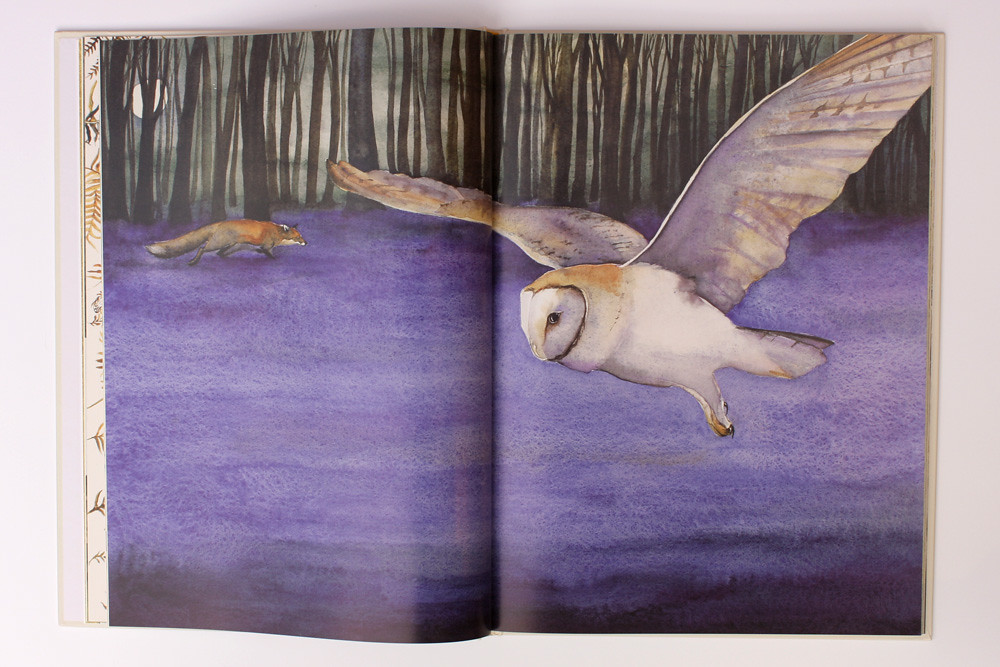

Third spread of Acorn. An oak tree, complete with green and brown acorns in their cups, is shown with an owl perched in its branches. Painting by Jackie Morris.

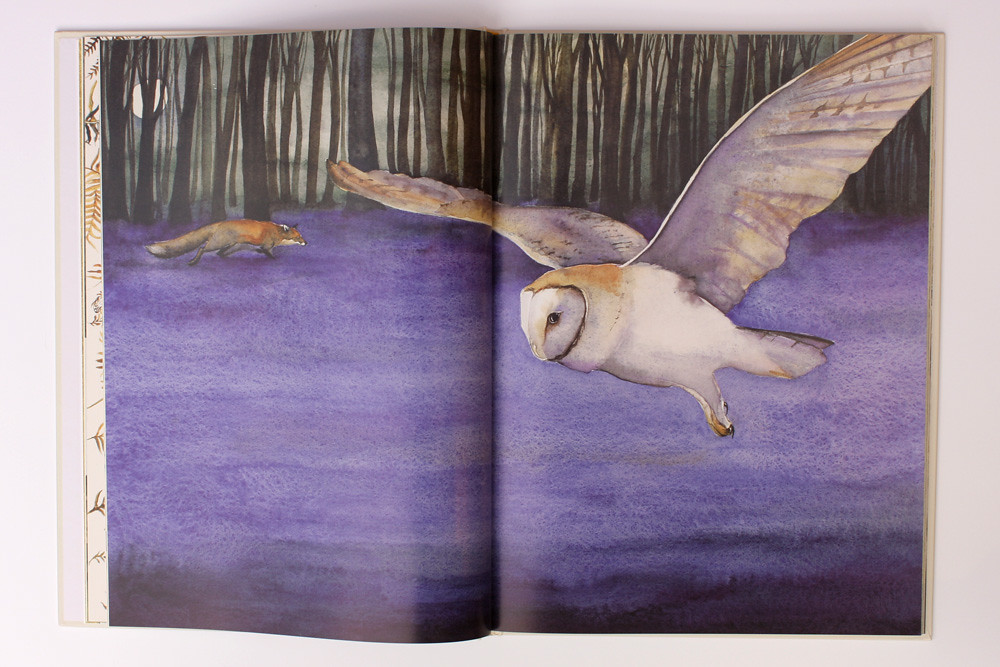

Top: Third spread of Bluebell. A moonlit woodland is carpeted with an ‘ocean’ of blue flowers. A fox runs through them and an owl flies overhead. Painting by Jackie Morris.

Why is it so popular? Well for a start this big book of poems and paintings about the natural world is truly beautiful, with high production values. Physically, it is sumptuous – large and heavy, with thick creamy pages that glow with a subtle sheen, rich gold lettering, and shimmery gold-leaf backgrounds for many of the pictures. Just handling it makes you feel as if you’re holding something of worth, something significant.

The book is heavyweight in a metaphorical sense, too, as the environmental message it conveys – about losing our awareness of nature – is deadly serious. Words matter, as by naming the creatures and plants of our world we show we value them. Words that were once common, such as bluebell, ivy, acorn, even magpie and conker, are apparently no longer recognised by many modern-day schoolchildren – or by many adults either.

The current exhibition at The Foundling Museum displays Jackie Morris’s watercolour paintings from the book, alongside simple printouts of Robert Macfarlane’s poems. The exhibition design is minimal, but the paintings are stunning. Exquisitely drawn and anatomically accurate, these iridescent images bring alive the plants and creatures they represent.

At the press view, Morris explains to me how the book came about. ‘The project was the result of being asked to sign a joint letter requesting the reinstatement of nature words into the Oxford Junior Dictionary,’ she says. The inclusion of such words was shrinking and being replaced with alternatives like blog, broadband, chatroom and celebrity.

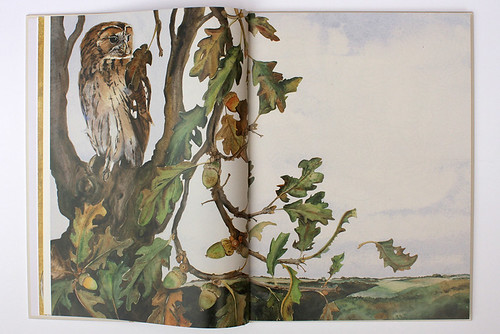

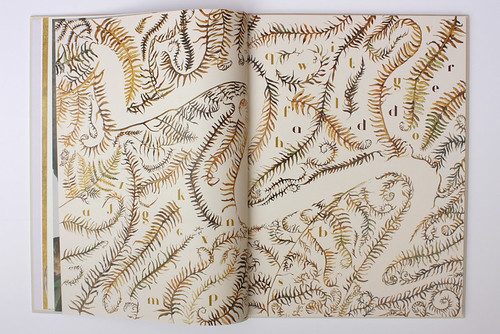

First spread of Adder. The area of white space indicates the ‘absence’ of the snake, while the darker letters hidden among the fern fronds spell the word ‘adder’. Painting by Jackie Morris.

‘That gave me the idea to do a book of definitions of nature words for children, which would be illustrated by pictures painted on gold leaf. I’ve used gold leaf for years, and for these illustrations I used a range of different colours – red gold (Weasel), yellow gold (Raven), green gold (Ivy, Newt and Fern), and moon gold (Bluebell and Lark).

‘I was hoping that Robert would write the introduction – but when I asked him he was keen to take the idea further, to make it a book for all ages. It was also Robert’s idea to make a triptych [a set of three pictures] to represent each word. The first image represents the “absence”, the second the “reconjuring” and the third the “appearance”, when you see the plant or creature within its appropriate setting.’

A real harmony of intent is evident in this book and when, later, Macfarlane joins us in the exhibition, he says: ‘The partnership between Jackie and me was a real tight weave of action and response. Her paintings were the truest illustration I’ve ever been involved with, and I kept being sent these golden visions down the email.’

Morris, who lives in a cottage on the cliffs of Pembrokeshire, also describes an intense emotional, almost spiritual, aspect of the project. ‘Sometimes, as I was painting, it felt as if I was having a conversation with the wild. For instance, when I had just finished the wren pictures, unusually I found a wren hiding beneath my van. Another day my dog came home with a raven’s feather that I drew and which ended up in the book.’

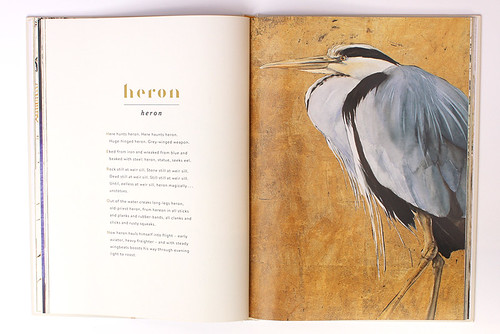

Second spread of Heron. Robert Macfarlane’s ‘spell’ appears on the left-hand page and Jackie Morris’s painting of the heron, on gold leaf, is on the right-hand page.

The book’s introduction urges the reader to speak the poems aloud, ‘to unfold dreams and songs, and summon lost words back into the mouth and the mind’s eye’. The very act of saying them out loud means the words are literally heard afresh. ‘I want the words to sound in the mind,’ Macfarlane says, ‘so you can almost taste them.’

Some of Macfarlane’s poems may be challenging for children to read out loud, and the language may be tricky – for example the use of the words ‘susurrus’, ‘burnish’, ‘furled’ and ‘wreaked’. But that doesn’t mean the verses are inaccessible. The fact that they are described as ‘spells’ is a thrilling notion, and there is a puzzle element to them, too, because each one is an acrostic – that is the first letter of each line spells out the flora or fauna being described. Even the nature word itself has to be discovered, as it is hidden within a jumble of apparently unrelated letters.

Some poems, such as Newt, are funny; others, such as Bluebell, are more of a meditation, in this case on the dreamy dense sea-like colour blue. Yet Macfarlane doesn’t flinch from the more cruel aspects of nature either. And some of the poems are darkly sombre – for instance, in Raven, there is a sinister echo of the fairytale Little Red Riding Hood with the words ‘I steal eggs the better to grow, I eat eyes the better to see, I pluck wings the better to fly’.

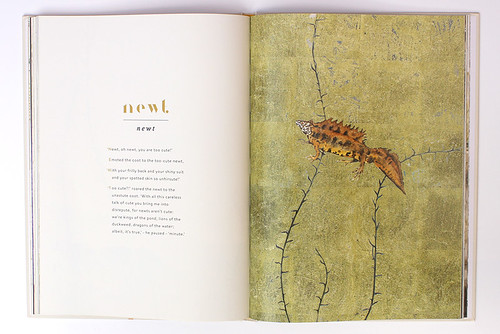

Second spread of Newt. Again Robert Macfarlane’s ‘spell’ is on the left and Jackie Morris’s painting is on the right. The background here is green gold leaf.

Macfarlane explains that he wished to catch the essence of each plant, bird or animal. ‘Gerard Manley Hopkins’ concept of “inscape” [the characteristics that makes a thing unique] was important to me,’ he says. ‘But I was also influenced by other poets, such as Seamus Heaney and Spike Milligan, and even Flanders and Swann.’

The Lost Words is a work by two artists at the top of their game, who care deeply about what they are doing and who are not prepared to compromise. ‘We knew we didn’t want to dumb the book down,’ says Morris. ‘With encouragement, children will embrace complex language, and the rhythm of Robert’s words is so beautiful. There really is a place for language like this in children’s literature.’

Amen to that!

* A proportion of the royalties from each copy of The Lost Words is being donated to the charity Action for Conservation, actionforconservation.org

Cover for The Lost Words: A Spell Book. Text: Robert Macfarlane. Illustration: Jackie Morris. Book designer: Alison O’Toole (Penguin Random House).

Clare Walters, writer, author of children’s picturebooks, London

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.