Winter 1994

Applying the lessons of the future today

The instant, push-button excitements of the digital wonderland blind us to the imaginative challenge posed by the new technology

In the late 1950s, Aldous Huxley reviewed his earlier prophecies in Brave New World Revisited and came up with ‘a very disquieting question: Do we really wish to act upon our knowledge? Does a majority of the population think it worth while to take a good deal of trouble, in order to halt, and if possible, reverse the current drift towards totalitarian control of everything?’

Huxley warned that the combined forces of overpopulation and the concentration of political and economic power through technology might pave the way for a ‘scientific dictatorship’ far more efficient and enduring than anything in history. But the 1990s is no time to be dismayed by such thoughts, even though we may think we have been warned of what is in store for us. Instead, we should look at things another way: what is truly exciting about multimedia, artificial intelligence, VR, neural networks, cybernetic surgery and various chemical cocktails that will pass away the small hours is the challenge they throw down to our imagination now, demanding and defying us to come up with something while we still have the chance.

First, there are more immediate threats to personal freedom to contend with. Here are just three none too distant possibilities: the increasing use of video surveillance in the city; smart cards that could be used to dock road tolls directly from us, as well as to police movement (where every driver leaves a digital spoor); central questions concerning the ownership, distribution and access to information raised by the Internet. Everyone must wake up to what sounds like an old and tired conflict – man versus machine. But does anyone want to wake up? If we are to achieve anything, we must reconsider some of the barriers we use to shield us from unpalatable truths.

The first of these is our instinct towards homeostasis, the urge to stay as we are, the fear of the unknown. This is exemplified by our attitudes to the media we consume, where ideas are encased in the familiar, preventing us from considering them afresh – as true of the fastest edit sequence in an advertisement as of a long-running theory or argument. Critiques of the mendacity of mass-media systems have become dull; there seems little to add to earlier dystopian visions of the twentieth century such as We, Brave New World and Nineteen Eighty-Four. Works predicting ‘the downfall of mankind’ date back to the Bible and beyond.

The direct threat of a robotic, fascistic regime that will rule the world seems to have evaporated, and the messages of Zamyatin, Huxley and Orwell can easily be made vaudeville. Indeed, Orwell’s barbed inversions (‘Freedom is slavery’, ‘Ignorance is strength’) were recently use by Time Out as the cryptic clues for a competition that gave readers the chance to win a case of Dutch lager and a weekend for two in Amsterdam.

Of course, it is only another weekly magazine, answers on a postcard. Orwell might add, ‘Knowledge is power’ – and the power to distribute information more powerful still. But the media environment is awash with those who abuse this power. The function of journalism is announcement, and like radio signals, they are best received with a minimum of interference. But too many of today’s reporters, critics and columnists blur their transmissions with the crackle of cynicism and one-upmanship, creating a climate of apathy and disdain. Hype, inside information, the tricks of the trade and the bottom line in sales terms all conspire in a network of exclusion. And behind the scenes, the media, busy in its manufacture of the ‘feelgood factor’, is often a lousy environment to work in. The messengers are no longer capable of being surprised or impressed, and the banality of their mass-produced words becomes infectious.

Numerous warnings have been given: this morning’s New York Times will contain more information than the average person was exposed to in a lifetime in seventeenth-century England, claims US writer and designer Richard Saul Wurman. But this stack of information, Wurman argues, does not further the reading public’s knowledge but instead helps to compound an increasingly common condition: ‘information anxiety.’ Information needs to be made more ‘understandable’, Wurman urges. But according to Neil Postman, the power and ubiquity of television and the reduction of every message to the status of entertainment has created a candyfloss culture which we avidly consume – and in doing so ‘amuse ourselves to death’.

Here is the double bind. Inconvenient ideas need to be stated and repeated. Yet to get through to the audience in our culture of protection, denial and closure, any book, programme or product must embrace the language of market forces, PR and advertising, or face disregard. The task for designers who wish to work with ‘serious material’, after a soft decade of easily located styles, is to come up with a distinctive approach that eschews sensationalism and shock tactics. But more often than not, books criticising the erosive power of the computer are designed to look like computer manuals.

Have the mental and physical states induced by the various levels of panic and insecurity governing an urban existence – at home, at work, on the dole, on the streets – become a prime source of entertainment in themselves? The linking of George Orwell with a crate of Dutch beer and a weekend city break starts to make sense. Escapism is actively encouraged; immunity can come only with the distance afforded by wealth – hence the increasingly important role of fantasy and illusion. This is not necessarily along the lines of a theme park blueprint: as George Steiner says, ‘There is something in us, very deep buried, that likes to think of catastrophe.’

For years we have been forewarned of the malign and powerful forces that might soon be set into motion, with little discussion of how we might mediate our fate. History is being revealed to us well in advance, and we think we can ignore it. Daily fears and longer-term doubts deter us from trying to map out the middle ground. The bombardment we have received extolling the virtues or damning the consequences of new technology has left us in a state of battle fatigue. At best, we are told, it is a question of keeping sensations sensational, for which we are promised a lot of future assistance: we can become electronic junkies, with the world our pharmacy. You might as well have fun while you can.

In his latest book, L’Art du moteur, Paul Virilio extends Nietzsche’s remark that, ‘What matters the most to modern man is not pleasure or displeasure, but to be excited,’ by saying that we have passed from the model of the Superman to one of ‘SuperExcitable Man.’ But this is the push-button excitement of a controlled climate. The instant sensation, the impulse and response of the Terminator become our vision of tomorrow, the special effects our refrigerated pleasure. Digital immobility, whereby we can supposedly fly across continents while rooted to the spot, will give us so much excitement that we will never again know the meaning of boredom. If you believe that, you will believe anything, and if you believe anything, what need is there for artificial substitutes?

In fact we are in a fortunate position, would we only rise to the challenge and chose the rarefied experience of actually doing something. We could start with the need to develop strategies that bring history – all the benefit of hindsight –programmed alongside the benefits of new machines. This cannot be stressed often enough. But the odds are stacked against it. How do you surprise people these days? Where is the initiative? Why does the first step seem like a backward step?

We must become alive to new opportunities and not be numbed by fear of the future. Just as urgently, we need to foster the potential for new languages to emerge from the digital realm, and not simply reformat the old. Upon looking at the past in order to anticipate the patterns of the future, you may find that all the essential messages have been stated again and again, and that few prophets ever had the bother of having to witness how, exactly, their cautionary tales might have crossed over into outcomes. You might also suspect that this current condition is new. But instead of feeling helpless, rather than looking on this legacy as a burden, we should see it as a head start.

Jon Wozencroft, graphic designer, editor of Fuse, London

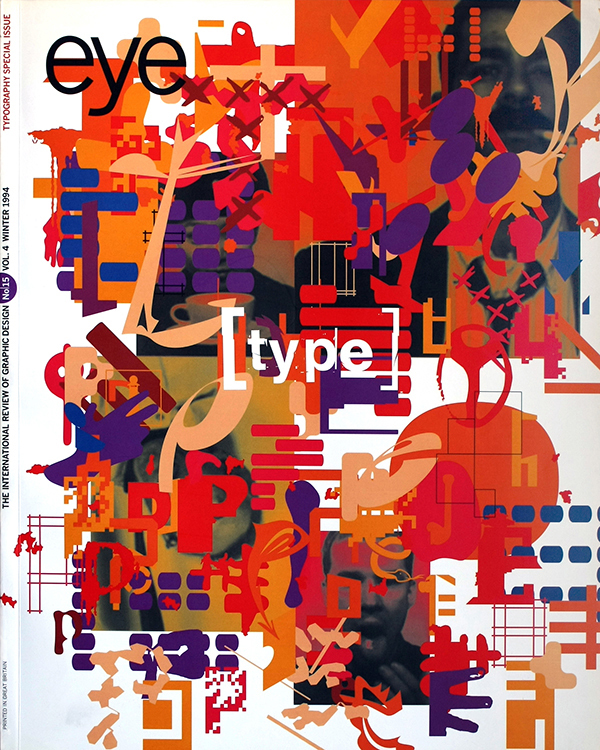

First published in Eye no. 15 vol. 4 1995

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.