Friday, 9:00am

25 January 2019

Awkward objects

The tradition of the painted still life has been reinvented by contemporary photographers with pictures that pose a puzzle and slow the viewer down. Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eyemagazine.com

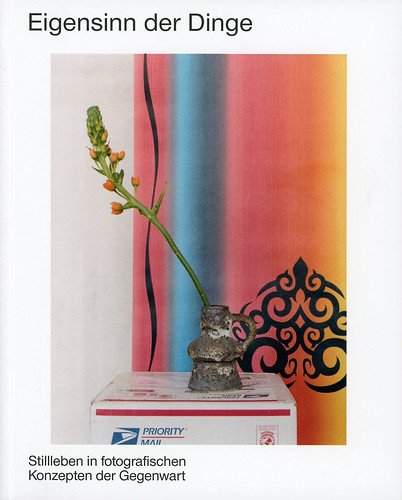

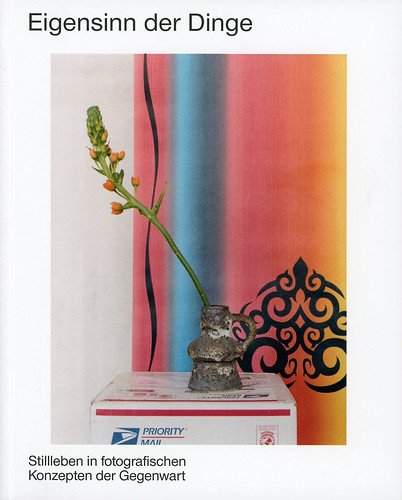

Annette Kelm’s photograph Untitled (Tribal) is a curiously resistant image. The objects it shows are perfectly ordinary – a vase, a stalk with budding flowers, a package for posting by priority mail – but the combination is awkward and unlikely, and the artificiality of the setting is similarly odd. There is a rainbow-like backdrop and some ornamental elements that look like they have been montaged into the image rather than existing three-dimensionally within the scene. Even the flower stem appears mismatched with the lumpy little vase. The plant crosses the black wavy line to create a deliberate-seeming but inexplicable focal point and the vase’s placement on this base seems equally arbitrary.

Cover of Obstinacy of Things showing Annette Kelm’s Untitled (Tribal), 2010.

Kelm’s picture occupies the cover of Obstinacy of Things, published by Spector, a book about contemporary photographic still lifes, which accompanies an exhibition at the Kunst Haus Wien in Vienna (until 17 February). The title issues a warning that these images could be slow to cooperate and give up their secrets and the show is bemusing and intriguing in equal measure. In Pizza Pizza Pizza (2016) Kelm presents four C-prints of the side of a takeaway pizza box covered at one end with a ragged piece of wood, perhaps from a fence, that casts an unnaturally black shadow, more like an ink stain, on the fierce yellow background. Could there be subtle differences to discover? None that meet the eye and, once again, the objects seem incongruous, although they are both forms of rubbish with no further purpose, except to make a photograph.

Andrea Witzmann, In the Wealth of Time 4, 2012. © Andrea Witzmann.

As a genre of painting, the still life always singled out and elevated the ordinary. Dutch and Flemish painters of the seventeenth century assembled lavish tables of meat, fish, bread, fruit and vegetables. Sometimes these foodstuffs were in a state of decay to impart a lesson about the perishability and transience of life. Because still lifes featured no human beings, they were regarded as the lowest form of painting, but to our eyes, centuries later, these celebrations of what some people consumed, or aspired to consume, are both jubilant and melancholy, as well as being valuable sources of information about material and culinary culture. In the hands of later painters, from Cézanne’s bowls of fruit to Morandi’s bottles and jugs, these ostensibly humble studies of mundane objects could often seem profound, as though some essential truth about existence had been teased out of the ordinary things around us.

Andrzej Steinbach, Untitled (record player), 2013. © Andrzej Steinbach. Courtesy Galerie Conradi Hamburg / Brussels.

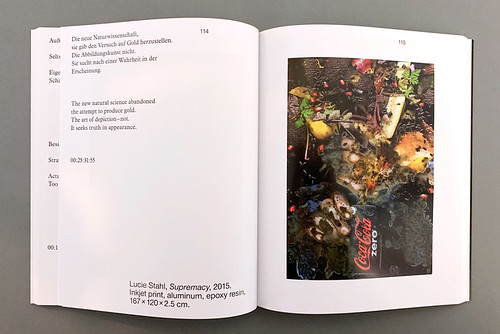

Today a superabundance of objects overwhelms us. Our domestic clutter borders on the pathological, while the image streams are so relentless that the sheer density of photos can seem self-annulling. Meaning comes from contemplation and speed erases that possibility. The ‘obstinacy’ of the pictures by 25 photographers in Obstinacy of Things lies in their assertion of what the book calls ‘their own logic, a pictorial self-will or autonomy’. (The German word for obstinacy, Eigensinn, can also mean ‘wilfulness’ or ‘strong-mindedness’.) The pictures’ recalibrated interior logic means that otherwise familiar objects no longer vouchsafe their purpose or import in the usual fashion. Sometimes it is not even clear what we are looking at. In Zoe Leonard’s pictures from 2000-3 of gum on the pavement (a contemporary blight) the blots look like rocks and planetoids adrift in swirls of cosmic dust. The organic detritus scanned by Lucie Stahl in Supremacy (2015) is collapsing into a ravishingly hued mulch, like a bountiful Flemish still life re-imagined as the malodorous jetsam in a landfill.

Spread showing Lucie Stahl’s Supremacy, 2015.

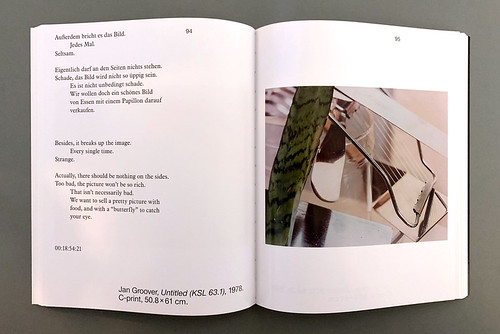

These strategies of re-enchantment can also be found in work by the late Jan Groover; Kelm cites her as an influence and the book has several pictures from 1978. In Groover’s ‘kitchen still lifes’, shot in warm, melting colour, we see glimpses in extreme close-up of sections of knives, forks, glasses, cooking utensils, vegetables and plant leaves. The objects overlap in unexpected ways, as though she has piled them up, and form angular, multi-layered compositions that verge on abstraction. Although Groover said that her motivations were solely aesthetic, in this company she looks like a forerunner of the contemporary mission to re-inscribe objects in photographs with the capacity to hold unmindful viewers’ attention and slow them down again.

Jan Groover, Untitled (KSL 63.1), 1978.

In the book, each picture has its own spread, the better to insist on its need to be absorbed without distraction. On the pages opposite, the editors, Bettina Leidl and Maren Lübbke-Tidow, unwind the transcript of Harun Farocki’s film about still lifes, Stilleben (1997). These bursts of text, set out like poems by the book designer, Jan Kiesswetter, often mesh with the images fortuitously: ‘In the end, objects bear witness to their producers, who reveal something of themselves in the act of production.’ By approaching their subjects obliquely and making them strange, these photographers incite viewers to think again about the myriad ways that we form attachments with our world of objects and come to inhabit them.

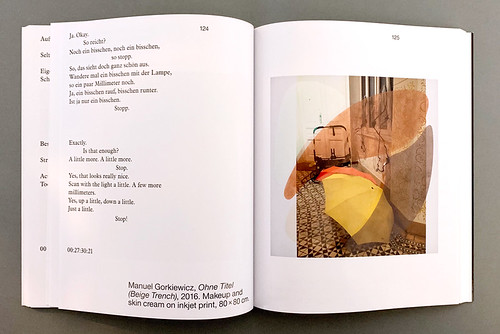

Manuel Gorkiewicz, Ohne Titel (Beige Trench), 2016.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.