Summer 2008

Craig Oldham

Who cares about graphic design history?

Craig Oldham was born in South Yorkshire and studied at Falmouth College of Arts (now University College Falmouth) where he graduated in 2006.

Q1.What do you think is meant by ‘the canon of graphic design history’? For example: The Bauhaus? Beck’s Underground diagram? Alvin Lustig’s book covers? Swiss Modernism? George Lois’s Esquire covers? etc. Do you ever think about it, or buy design history publications?

A1. If, by the word ‘canon’, we mean a collection of sacred items, then all your examples belong in the vault. And an awful lot of others.

Graphic design is the universal language of communication and a canon should contain timeless, pioneering work that has defined the visual language and aesthetic of their respective era and influenced the years that have followed – that’s as simple as I could put it. I buy too many design history publications for my own good. I’m after Milton [Glaser]’s Dylan poster right now. I have tomes dedicated to the subject, piles and piles of the memoirs of the famous and influential. These books are important to me. I hate to think where would I be without my trusty Megg’s History of Graphic Design. (Now there’s a book every design student should have.)

Q2. Does this kind of design history have relevance to your own practice?

A2. Yes. Of course. And I know design history holds relevance for other working designers. Remember Paula Scher’s homage to Herbert Bayer for Swatch watches? Tibor Kalman claiming that Scher, along with Carin Goldberg and others, were ‘pillaging design history’? Seymour Chwast recognises this also: ‘Education in the broadest sense – meaning exposure to all aspects of our history and culture – has been vital to my design ability; but technique and craft have to be learned as well.’

Yet the line between design history and design future is thin and blurred. Some camps believe that there is no such thing as a new idea; others strive to produce nothing but original work.

Mike Dempsey (of CDT) recently indulged in a bit of soul-searching by stating that graphic design had hit a watershed, had plundered all stylistic trends and could only go backwards from here. I am not so sure about that. Sure, designers have always been inspired by movements and design icons, but to say that going backwards is the way forward is quite a paradox. Be influenced and inspired by design history but when solving problems, do it in a new and original way.

Q3. Where did you learn about design history?

A3. At Falmouth. My college course placed particular emphasis on the importance of design that has been and how it can influence, inspire and progress what is to come. And they creatively named it HACCS (something along the lines of Historical and Contextual Cultural Studies).

Not only did we devote a full day’s slog to HACCS, with lectures, readings, presentations and films, all on the history of design, but we also had more concentrated, one-off case studies on topics such as Modernist typography, postmodernism, consumerism and the Bauhaus. The focused lectures affected me profoundly as a designer.

I remember seeing work by Rodchenko and El Lissitsky, Robert Brownjohn and Herbert Spencer, and being overwhelmed. Not only did they confirm that I too wanted to be a designer but they gave me that ‘How the hell do I follow that?’ feeling. But in a good way of course.

These classes introduced me to design history, but it is my personal reading that has furthered it.

Q4. Does history have any relevance to the new technology and techniques you’ve had to master in your work?

A4. Many have debated, and still do, that typography is the closest thing to a trade that graphic design has, and it is a trade that all designers have to master. History is utterly relevant to typography and the technology used to produce it. The computer and digital technology may have made the process of typography quicker, however the skill and craft that comes into it requires a detailed and rich knowledge of the techniques used twenty, 50 or 100 years ago. Kerning is still kerning, leading is still leading, and widows are still widows, regardless of time passed or the technology used.

History, and design history canons in particular, can bridge this gap of time and provide a valuable reference tool on which to produce better, more crafted work.

Q5. If you were in charge of a design education programme, what aspects of design history would you teach to your students?

A5. As much as possible. I don’t think there is enough design history taught in design education. And what is taught tends to be glossed over. I worry that a designer may know the names of David Carson, Neville Brody and Stefan Sagmeister, however I think they’d struggle to recognise Müller-Brockmann, Piet Zwart and Jan Tschichold. They are probably even less familiar with designers such as Brownjohn, Glaser, Lubalin and Crouwel.

Students should know these designers. They should know the times in which these designers practised, be familiar with their beliefs and principles (used loosely), as it will help them define who they are as a designer and how they will ultimately work. They’ll grow in terms of understanding their creativity, knowing whether they design intuitively or rationally, and to what extent. It is this examination of design history that allows a student of design to progress and find their place within design.

I would also be more specific were I to educate students. I would lecture on posters alone, books alone, brands alone, design for music alone and typography alone, as well as others, as each field within design has its own story to be told respectively. You cannot compare and contrast a poster with an album cover, or a book with a logo, just because they might be from the same movement or period. It’s chalk and cheese. A different box of frogs.

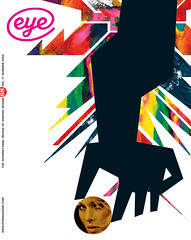

First published in Eye no. 68 vol. 17 2008

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.